The story of the United States’ rise to global power is inadequately understood in part because its contours are so familiar. The most prominent narrative, reiterated in the country’s political discourse, holds that the United States oscillated between “isolationism” and “internationalism” until the latter prevailed around the middle of the twentieth century. Many scholars question that dichotomy; instead, they see the United States as constantly expanding its power, vaulting thirteen backwater colonies into a globe-spanning superpower. Yet both lines of interpretation assume that most, if not almost all, U.S. policymakers consistently intended to enlarge the United States’ strategic space until it spanned the world. These interpretations overlook that the very people who made U.S. ambitions global had long planned to do nothing of the sort until unanticipated events shocked them into changing their minds.

This essay asks how and why the United States reversed course and made a decision for dominance. Building on my book Tomorrow, the World: The Birth of U.S. Global Supremacy (2020), it shows how U.S. planners leapt from a hemispheric to a global mental map of U.S. interests and responsibilities within a period of five months in 1940. Then it assesses the drivers of the shift, which has proved enduring in the eight decades since.

Empire without Entanglement

Prior to World War II, the United States enlarged its strategic space through three distinct, albeit overlapping, modalities. The first was the process of so-called westward expansion across North America through the conquest and settlement of contiguous territory incorporated into the federal union as states. The second was formal colonialism: the United States acquired noncontiguous territories—Guam, the Guano Islands, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands—and ruled them without intending to grant them statehood. Third, the United States claimed a sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere, announced in the Monroe Doctrine of 1823, and policed the greater Caribbean region from the late nineteenth century onward. It is not for nothing that scholars have deemed the United States to be a relentlessly expansionist nation.

Yet narratives of untrammeled enlargement often obscure countervailing sources of U.S. restraint. While seeking ascendancy over what it styled as the “new world,” the United States also resolved to avoid political-military entanglements in the “old world,” especially on the Eurasian landmass and even more particularly in Europe. This traditional consensus did not erode over time in a linear fashion. In fact, it deepened in the two decades following World War I, as regretful Americans sought to stay out of any new war. So when World War II began in Europe in September 1939, there was little appetite to enter. Officials in Washington assumed not only that the United States would decline to join the conflict, but also that after the war it would and should assume no obligations to use military force outside U.S. territory and the Western Hemisphere.

Until May 1940, an essentially hemispheric mental map of the U.S. defense perimeter was widely shared in the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It also guided the conduct of postwar planning by a group of nearly one hundred experts who gathered in the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), receiving direction from the U.S. Department of State and funding from the Rockefeller Foundation. The experts convened by CFR were the country’s foremost postwar planners before the attack on Pearl Harbor drew the country into the war. Their specific plans were overtaken by events, but they devised a global conceptualization of U.S. interests and responsibilities that would form the premise for the State Department’s official postwar planning committee, established in 1942, with CFR experts providing its backbone.

The ranks of CFR planners included Cold Warriors to-be such as the future CIA director Allen Dulles, who led a group of military experts. Yet Dulles and company were not gearing up for cold or hot wars even as the Nazis made advances during the spring of 1940. Instead, they catalogued schemes for universal disarmament stretching all the way back to the ancient Greeks’ prohibition on poisoning wells. Dulles and his fellow planners still hoped that peaceful, liberal modes of interaction—such as trade, mediation, and law—would tame the system of power politics that bedeviled Europe and Asia. At any rate, U.S. interests overseas warranted little more.

The Grand Recalculation

Then Nazi Germany shocked the world and conquered France within a six-week period during May and June 1940. The collapse of the Third Republic, formerly boasting the world’s strongest army, destroyed the European balance of power. American observers projected that Germany would control the continent for the foreseeable future and might even seize Britain and its empire. The fall of France spurred U.S. elites to recalculate the United States’ strategic space. At the State Department’s request, CFR planners began assessing how much of the world the United States needed to defend now that liberal forms of international exchange, far from being able to tame power politics, had to be defended by armed force in order to survive. As France was falling, geographer Isaiah Bowman told the group that all postwar planning must proceed from the following assumption: “Only force will make and keep a good peace.”1

Led by a pair of economists, including Alvin Hansen (known as the “American Keynes”) and Jacob Viner, the planners got to work. At first, anticipating that Adolf Hitler’s forces might swiftly capture Britain, the planners assumed that the United States would henceforth be confined in all of its international interactions to what they called a “quarter-sphere,” extending from North America down to where Brazil juts into the Atlantic. A quarter-spheric future was hardly desirable to the planners. But they also concluded that it was far from catastrophic. If the United States traded only within the quarter-sphere, its economy would perform adequately. Although the country would lose two-thirds of its foreign trade, the U.S. economy was overwhelmingly self-contained, exporting less than 3% of its GNP outside North America during the 1930s.2

Hansen judged the quarter-sphere to be an “excellent economic unit for the essential defense of the United States,” and one that the United States possessed the naval power to protect.3 In short, the United States could remain remarkably safe and prosperous regardless of what happened in Europe and Asia.

But the quarter-sphere construct was superseded within a matter of months. Across the Atlantic, Britain did not succumb to France’s fate, showing instead that it might survive the Nazi onslaught. This enabled the United States to envision forming a wartime and postwar alliance with a capable but weakened Britain, in which Washington would be the senior partner to London. At home, quarter-spheric perimeters had few political supporters. Even the antiwar figures who gathered in the America First Committee wanted to keep the Axis powers out of the Western Hemisphere in accordance with the Monroe Doctrine. For more forward-leaning elites, including President Roosevelt, defense of the hemisphere was the baseline minimum.

Starting in July 1940, CFR planners began to enlarge the United States’ strategic space, at first to the whole hemisphere. Alas, they deemed the Western Hemisphere an insufficient unit. It could not absorb large surpluses of agricultural goods that South America typically exported to Europe. Those surpluses mattered chiefly for geopolitical reasons, not because the planners were stringent free-marketeers and economic maximizers. Their basic aim was to map a postwar area that would be more economically self-sufficient than a projected Nazi-led greater Europe, meaning that the U.S.-led area would be less dependent on external trade. That way, the United States would possess superior bargaining power and keep its area cohesive during the indefinite armed truce expected to follow the war. Moreover, the planners, seeking to preserve liberal capitalism, wished to avoid regimenting the economy as a means of resolving trade imbalances. That left only one way to get rid of surplus goods: expand the area under U.S. protection.

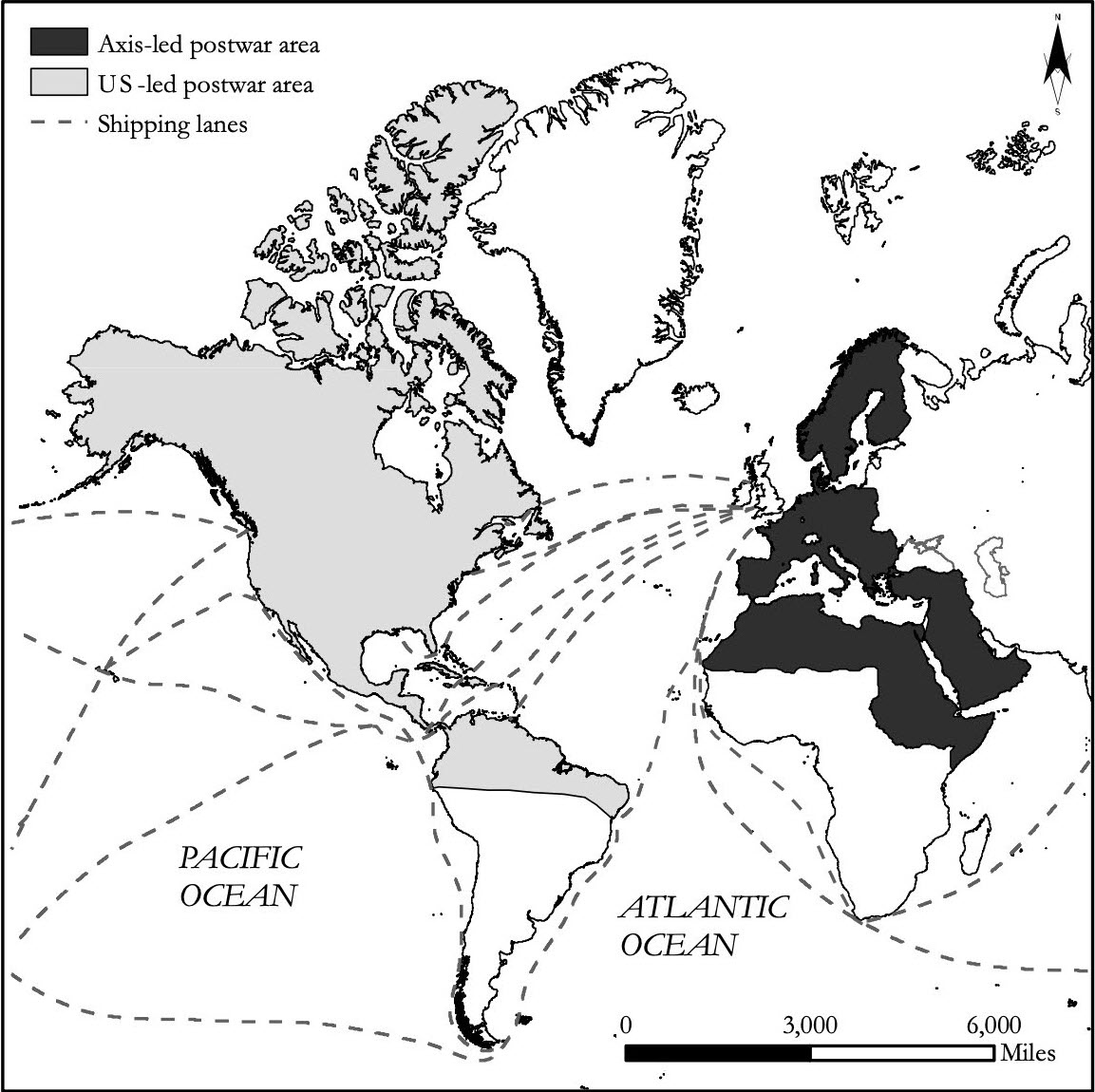

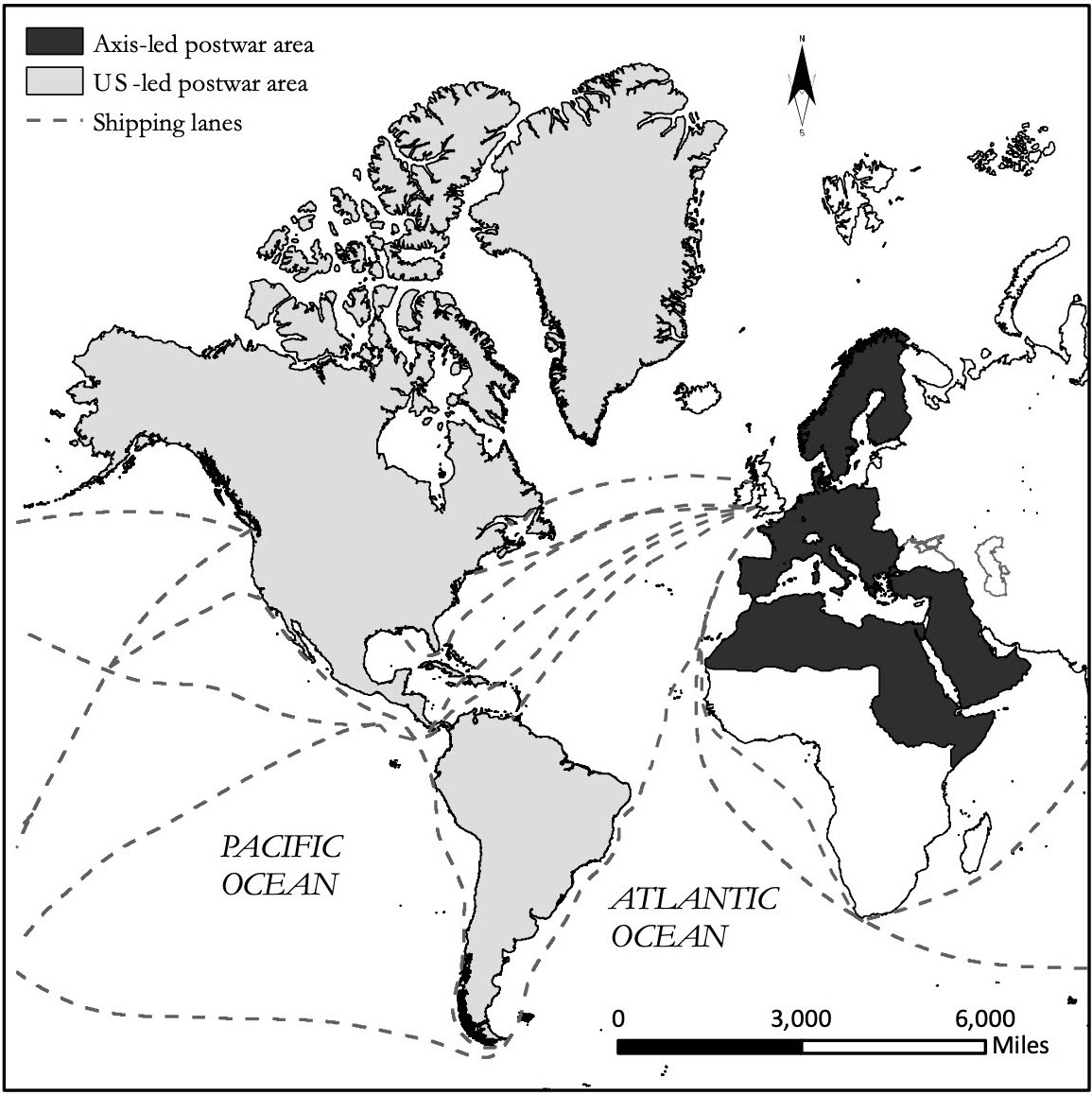

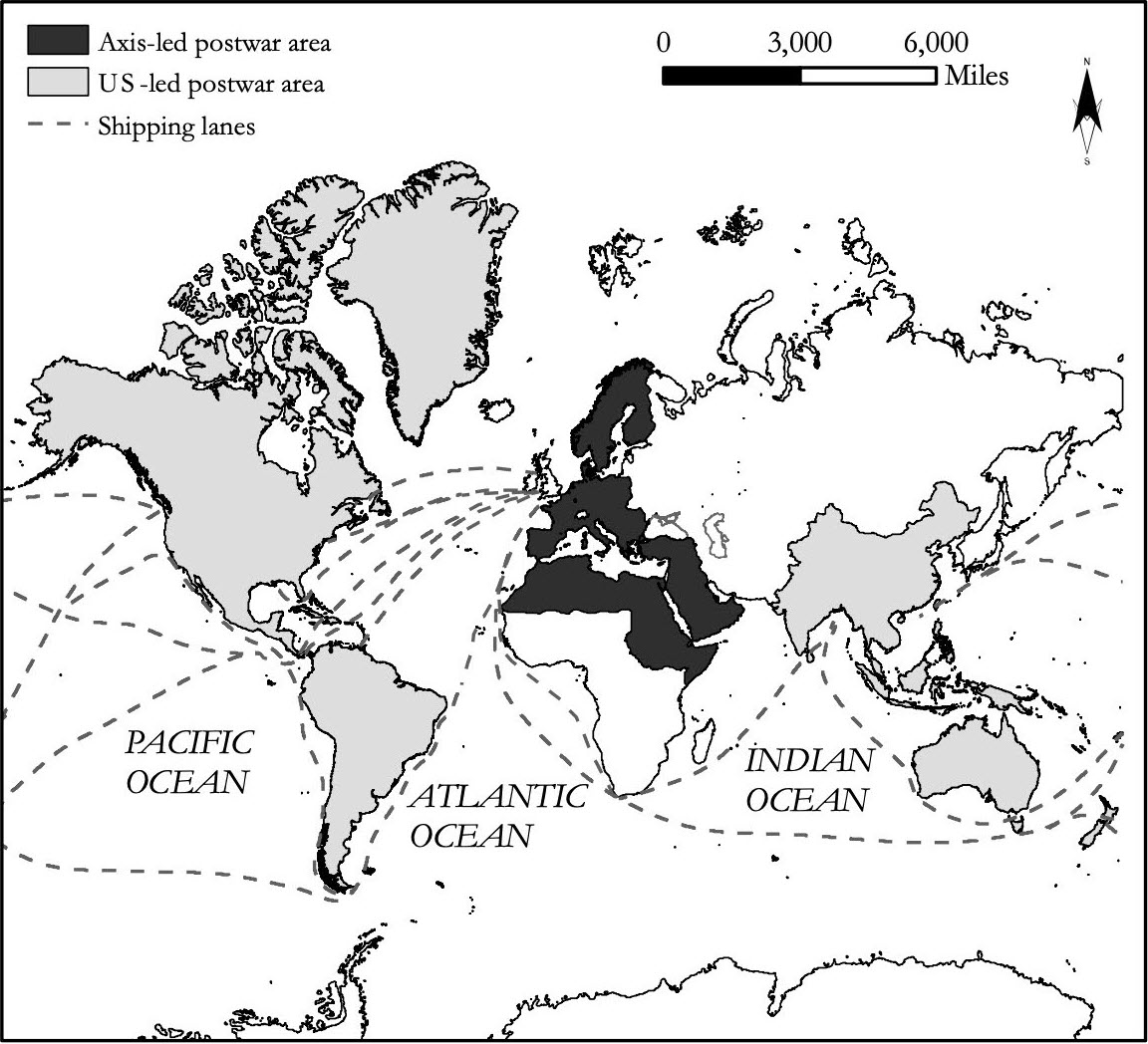

In September, the planners did just that. Breaching hemispheric boundaries, they added in a massive Indo-Pacific region. Entering the U.S.-led area were Australia, India, Southeast Asia, and Japan (which the planners hoped to integrate even as Tokyo was joining the Tripartite Pact with Berlin and Rome). Yet these ample additions were still insufficient. Although they would help the U.S. economy, they offered no relief for the agricultural surpluses in South America. The Axis-led area would be more economically self-sufficient than the U.S.-led area and so would hold the geopolitical advantage.

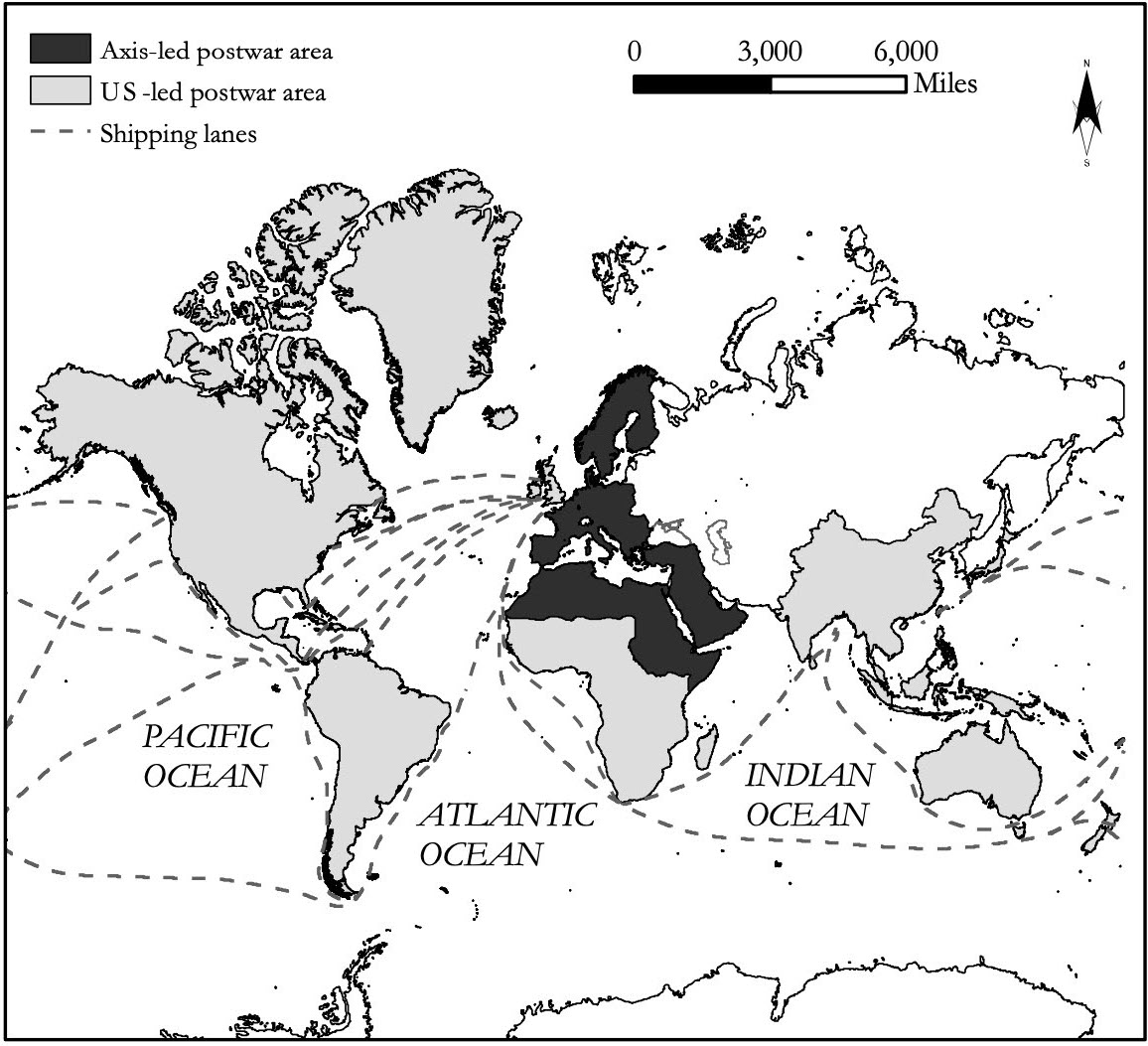

In October, therefore, the CFR planners added everything else they could, namely the rest of the British Empire and the British Isles, which could absorb Western Hemisphere trade surpluses. Finally the planners had found an area—the Grand Area, as they dubbed it—that they calculated to be “substantially” more self-sufficient than a Nazi-led Europe. By their reckoning, the Grand Area could consume 86% of exports by its constituent countries and supply 79% of imports, compared with 79% and 69%, respectively, for Europe.4 In the span of five months, the planners had reached a startling conclusion: the United States must hold “unquestioned power” in the world. As they summarized, “The United States should use its military power to protect the maximum possible area of the non-German world from control by Germany in order to maintain for its sphere of interest a superiority of economic power over that of the German sphere.”5

Other Americans reached conclusions similar to those of the postwar planners, but without the need for maps and statistics. One of them was the publishing mogul Henry Luce, who in February 1941 announced the beginning of the “American century” in an instantly famous essay by that name: “Tyrannies may require a large amount of living space,” he wrote. “But Freedom requires and will require far greater living space than Tyranny.”6

Stephen Wertheim is a Senior Fellow in the American Statecraft Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He is also a Lecturer at Yale Law School and Catholic University.

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

The author wishes to thank Bill Keegan and Kristen Noble Keegan for the maps appearing in this essay.

ENDNOTES

Explaining the Global Turn

Citing the economic calculations underpinning the creation of the Grand Area, some scholars have interpreted the CFR planners as seeking, above all, to promote the growth of the U.S. economy and the health of international capitalism. To be sure, the planners wanted to ensure a prosperous national economy and international capitalist space. But a neo-Marxist interpretation overlooks the fact that the planners assessed that the mere quarter-sphere would suffice for the United States’ essential economic needs. What rendered the quarter-sphere untenable was a political consensus, rooted in the U.S. determination to keep outside powers from encroaching on the Western Hemisphere, and then a desire to obtain geopolitical advantage for the hemisphere by enlarging the order in which it was embedded.

Despite the elaborate nature of the study, its calculations remained suspiciously crude. The planners focused on international trade in goods and ignored the industrial capacity of states. For that reason, the study bracketed the Soviet Union, which conducted little international trade and throughout 1940 remained officially neutral toward the war. Moreover, to assess trade patterns, the planners relied on statistics for the year 1937, taken as a proxy for the future.

Given these limitations, the Grand Area study might matter less for its specific calculations than for the capacious objectives it sought to secure. The planners intended to achieve much more than safety and prosperity for the United States and the maintenance of its liberal-capitalist economy. They wanted the United States to guard at least the entire Western Hemisphere and then defend enough of the world such that Washington would possess superior bargaining power over any area that came under totalitarian control. Thus, the quest for geopolitical advantage by an emergent liberal order, more than the search for new profits via new markets, is what drove the planners to enlarge the United States’ strategic space to encompass the Grand Area.

Still, if liberal geopolitical concerns were truly the sole driver, the CFR planners should have altered their prescriptions as the war went on. As the prospects for Axis control of the European continent diminished, U.S. hegemony across the postwar Grand Area should have appeared less desirable. The Grand Area’s ostensible reason for being was to give the United States the edge in a prolonged standoff against Germany and its sizeable conquests. But starting in 1941, as it looked increasingly possible to defeat the Axis powers rather than compete indefinitely with them, the planners did not take this good news to mean that the United States should revert to a hemispheric defense posture once the war was won. To the contrary, the planners further enlarged the Grand Area. They came to envision nearly the entire world as the United States’ strategic space, seemingly regardless of geopolitical circumstance. By 1945, the United States had achieved victory in Europe and Asia and set out to hold onto a preponderance of global power, with most centers of industrial and military power aligned with and protected by Washington. The Soviet Union threatened that preeminence as the Red Army raced westward to Berlin. U.S. policymakers then had to decide whether to accommodate a Soviet sphere of influence or actively contain Communism as they had worked to contain Axis Europe in 1940 and 1941.

A kind of geopolitical logic might explain why the Grand Area gave way to an indefinitely global strategic space even before the United States formally entered World War II. Having concluded that the United States should protect the “maximum possible area” of a world threatened by totalitarian mass conquest, postwar planners reasoned that the United States should also prevent totalitarian mass conquest in the first place and never again revisit the bleak set of choices that the country faced in 1940.

At the same time, such a maximalist geopolitical stance, which would commit the United States to open-ended international activity and unknown costs, might also amount to the geopolitical expression of a universalistic ideological impulse. The United States had long sought to live in an international environment where it could interact and transact on liberal terms. And it had long imagined itself as leading world history in an American direction. Those twinned commitments—call them internationalism and exceptionalism—had previously appeared consistent with a hemispheric defense perimeter. But once totalitarian powers came close to steamrolling across Europe and Asia, it seemed that the United States could enjoy a liberal and American international order only if it prepared to defend that order by force. Even after the specific Axis threat receded, the United States would need to maintain primacy in a world that had proved susceptible to domination by the worst forces known to humankind.

Other Americans reached conclusions similar to those of the postwar planners, but without the need for maps and statistics. One of them was the publishing mogul Henry Luce, who in February 1941 announced the beginning of the “American century” in an instantly famous essay by that name: “Tyrannies may require a large amount of living space,” he wrote. “But Freedom requires and will require far greater living space than Tyranny.”6

Stephen Wertheim is a Senior Fellow in the American Statecraft Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He is also a Lecturer at Yale Law School and Catholic University.

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

The author wishes to thank Bill Keegan and Kristen Noble Keegan for the maps appearing in this essay.