In the early 2000s, Chinese leaders foresaw a period of strategic opportunity that they believed would enable the country’s rapid development. By the 2010s, however, the benign international environment became more hostile as an increasingly powerful China experienced a rise in tensions with the United States and some of its allies and partners. More importantly, China’s domestic situation deteriorated as decades of rapid growth generated destabilizing levels of inequality, corruption, and discontent over official malfeasance. Anxious Chinese leaders have elevated national security as a priority and sought to manage various international and domestic risks.

The Onset and Decline of the Period of Strategic Opportunity

At the 16th Party Congress held in 2002, the president of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) Jiang Zemin stated, “the first two decades of the 21st century are a period of important strategic opportunities, which we must seize tightly and which offers bright prospects.” He described a “peaceful” international environment and relatively stable domestic situation. The benign environment permitted Beijing to prioritize national development in pursuit of national rejuvenation by midcentury. In Jiang’s words, “The two decades of development will serve as an inevitable connecting link for attaining the third-step strategic objectives for our modernization drive” to be accomplished by the 100th anniversary of the founding of the PRC in 2049.[1] The government did not provide an explanation as to why the period of strategic opportunity would last two decades, but the time frame was likely designed to accord with the policy benchmarks of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), collectively known as a “moderately prosperous society,” set to coincide with the 2021 centenary of the CCP’s founding.[2]

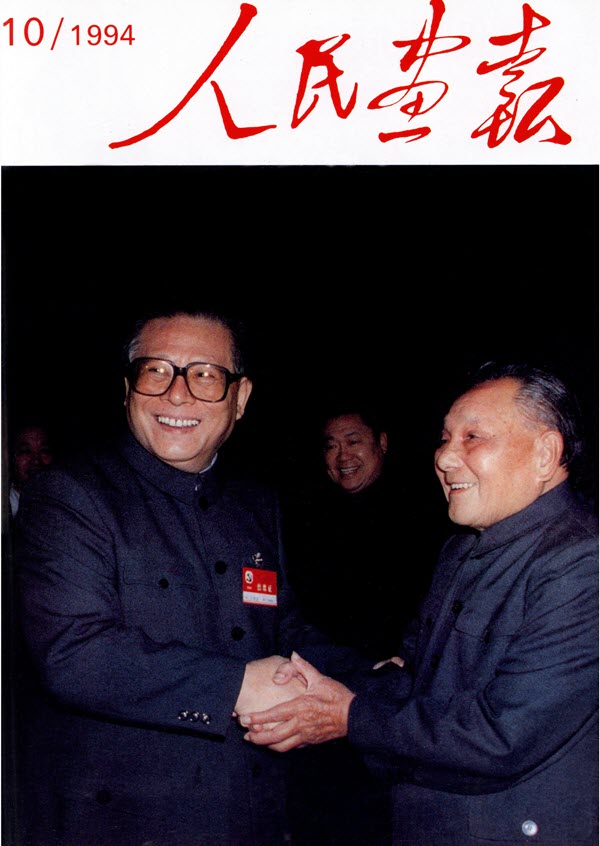

Chinese scholars have explained that the origin of this judgment originated with Deng Xiaoping. In the 1990s, Deng declared that China faced an opportunity to focus on development.[3] The designation of a period of strategic opportunity included several important judgments about the international environment. The first one involved a lack of a major enemy. Throughout the Cold War, China regarded war with either the United States or the Soviet Union as distinct possibilities and prioritized defensive preparations accordingly. But once relations with the United States thawed and the Cold War ended, China no longer faced a threat of major war. Second, Chinese leaders judged the international system as offering many opportunities. Thus, Beijing no longer needed to promote international revolution but could instead develop within a U.S.-led order. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and China’s entry in the World Trade Organization (WTO) that same year added impetus to this view. The United States focused on fighting international terrorism and accordingly did not apply much strategic pressure on a rapidly growing China. The WTO accession corresponded with a major increase in Chinese economic growth as the world market provided lucrative opportunities for Chinese industry.

In the ensuing years, China’s economy enjoyed rapid gains. From 2001 to 2008, China’s growth outpaced credit, permitting breakneck growth to coincide with relatively stable national finances. U.S.-China relations experienced tensions and near crises over Taiwan and other issues, but both countries maintained a tense cooperative relationship overall.

However, judgments about the duration of the period of strategic opportunity changed in the 2010s owing to a deterioration in the domestic and international environment. Rapid credit expansion in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis deepened China’s dependence on debt with diminishing returns.[4] Moreover, the costs of rapid growth accumulated over time, exacerbating problems of inequality, ecological despoilation, corruption, and crime. By 2011, spending on internal security exceeded defense spending.[5] Despite repeated attempts to put the nation’s growth on a sustainable footing during the 2010s, debt worsened and the economy grew ever more imbalanced. Population decline, which began in 2022, added additional downward pressure on the country’s prospects. Economists have revised China’s prospects downward, with some analysts predicting the country’s growth rate could slow to 2%–3% annually through midcentury.[6]

Strategists also began to perceive a worsening international environment. They warned that the coming years would involve greater tensions with a United States experiencing relative decline. Echoing a theme widely observed in Chinese analysis in recent years, then vice president of the Chinese Institute of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR) Wang Zaibang regarded as “unquestionable” that the “generally advantageous position of the developed countries in Europe and America will gradually and irreversibly fall.”[7] Lin Limin, a scholar at CICIR, predicted in 2011 that Western countries would “lose the superior position that they have held for hundreds of years.” He anticipated a “breakdown in the international system dominated by the West” that would open opportunities for China and other developing countries to reorder a more peaceful world.[8]

The judgment by Chinese scholars that the West would continue to decline and the rest of the world experience a relative rise gained official backing when Xi Jinping assumed office. By the mid 2010s, Chinese officials began to employ the phrase “great changes unseen in a century” to refer to these general trends of relative decline of the West and rise of the non-West.[9]

These “great changes” were expected to result in heightened tensions between the West and non-West. The U.S. strategic pivot to the Asia-Pacific, which began near the end of President Barack Obama’s tenure, appeared to confirm Chinese fears. [10] Niu Xinchun, a scholar at CICIR, argued in 2012 that the “greatest obstacle to the further integration of emerging countries such as China into the international system comes from the United States.”[11] In 2015, PLA deputy chief of staff Qi Jianguo observed that “no conflict and no confrontation does not mean no struggle” between China and the United States.[12]

Chinese leaders thus continued to perceive strategic opportunities for national development, but also a dire security situation. At the 20th Party Congress, Xi stated that China had “entered a period of development in which strategic opportunities, risks, and challenges are concurrent and uncertainties and unforeseen factors are rising.”[13] Similarly, the 2019 defense white paper stated that China is “still in an important period of strategic opportunity for development. Nevertheless, it also faces diverse and complex security threats and challenges.”[14]

The increasing severity of the dangers suggests that the opportunities for development may be more fragile and tenuous than was the case in the decade that followed the turn of the century. Chinese leaders have depicted domestic threats as particularly menacing. When Xi described the threats to national security at the 20th Party Congress, he began by listing issues of “social governance,” likely referring to popular discontent over corruption, inequality, and local malfeasance. He then mentioned “ethnic separatists, religious extremists, and violent terrorists” as well as organized crime and natural disasters.[15] Similarly, in a 2019 speech in which Xi outlined seven “major risks” to China’s pursuit of the “China dream,” he listed dangers related to “politics,” “ideology,” “the economy,” “science and technology,” “society,” “the external environment,” and “party building.”[16] Only the dangers posed by the “external environment” implied a potential miliary threat. Explaining, Xi characterized the external environment as “complex and grim” and urged officials to “guard against various risks acting in conjunction with one another like a chain.” Elsewhere he has warned about pressure by Western countries. In 2023, for example, he stated that “Western countries headed by the United States have contained, encircled and suppressed China in an all-round way, bringing unprecedentedly severe challenges to China’s development.”[17]

The palpable anxiety over compounding dangers helps explain why Beijing has prioritized security and risk management. In 2013, China established the National Security Commission and two years later passed the National Security Law. Xi has explained that security and development are mutually interdependent, and he has accordingly demanded that officials attend to the security dimensions of virtually every aspect of national power.[18] A profound sense of insecurity appears to underpin the interest in security. To cope with insecurity, Xi has also repeatedly emphasized the importance of managing and reducing risks.[19]

Conclusion: The CCP Prepares for Its Second Century

In the year 2049, the PRC will be one hundred years old. That may be an impressive achievement, given the usually short lifespan of countries ruled by Communist parties. But a PRC that reached the century milestone would also remain young compared to major modern nation states such as the United States, which reached its second centenary in 1976. Moreover, by the measure of Chinese imperial history, a PRC that is one hundred years old would rank as only a modest achievement. The two most immediately preceding dynasties, the Ming and Qing, each lasted roughly three hundred years. In light of the CCP’s disparagement of imperial dynasties as “backwards” and inferior, it would be humiliating in the extreme if the party barely survived beyond its first century in power.

This long-term perspective can help explain why Beijing has adopted such a cautious approach to the next few decades. From Beijing’s perspective, its principal responsibility lies in preserving China’s modernization gains and avoiding disastrous missteps. Chinese leaders are already thinking about the second century. Chinese media explains that the sixth plenary session of the 19th Party Congress, held in 2021, began initial guidance for “the second century of the CCP.”[20] In sum, the period of strategic opportunity is not only aimed at providing a glide path to reach a centenary celebration by midcentury. It is designed to establish the foundations for a CCP-ruled China that can endure well past its first century.

Timothy R. Heath is a senior international defense researcher at the RAND Corporation.

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

Cover of the China Pictorial issued in October 1994 features Deng Xiaoping, former Chinese leader, right, shaking hands with Jiang Zemin, then Chinese president | Imaginechina Limited / Alamy Stock Photo

Shi Guangsheng, then Chinese Minister of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation, signing the protocol on China’s accession to the WTO in Doha, 2001 | © WTO

Sudden stock market crash chart | marcos alvarado / Alamy Stock Photo

ENDNOTES

[1] “Full Text of Jiang Zemin’s Report at the 16th Party Congress,” Xinhua, November 17, 2002.

[2] “Xi Declares China a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects,” Xinhua, July 1, 2021.

[3] Zhang Yuyan, ed., Xi Jinping Xishidai zhongguo teshe shehuizhuyi waijiao shixiang yanjju [Study on Xi Jinping’s Diplomatic Thought of the New Era of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics] (Beijing: China Scientific Socialist Press, 2019).

[4] Jude Howell and Jane Duckett, “Reassessing the Hu-Wen Era: A Golden Age or Lost Decade for Social Policy in China?” China Quarterly 237 (2019): 1–14.

[5] Jeremy Page, “Internal Security Tops Military in China Spending,” Wall Street Journal, March 5, 2011.

[6] Roland Rajah and Alyssa Leng, “Revising Down the Rise of China,” Lowy Institute, March 14, 2022.

[7] Wang Zaibang, “Historical Change Shows that Systematic Adjustment Is Urgent; Review of and Thoughts on the 2008 International System,” Contemporary International Relations, January 20, 2009, 1–6, 19.

[8] Lin Limin, “China’s Foreign Strategy: New Problems, New Tasks, New Ideas,” Contemporary International Relations, November 20, 2010, 23–24.

[9] “Full Text of Xi Jinping’s Report to the 20th Party Congress,” Xinhua, October 25, 2022.

[10] Cui Liru, “China’s Period of Historic Opportunities,” China-U.S. Focus, February 1, 2018, https://www.chinausfocus.com/foreign-policy/chinas-period-of-historic-opportunities.

[11] Niu Xinchun, “Zhong mei guanxi: Yishi xingtai de pengzhuang yu jingzheng” [U.S.-China Relations: Collision and Competition of Ideologies], Guoji wenti yanjiu, March 13, 2012, 78–89.

[12] Xiong Zhengyan, “Firmly Advance Down the Path of National Security with Chinese Characteristics: Interview with Sun Jianguo,” Outlook, May 5, 2015.

[13] “Full Text of Xi Jinping’s Report to the 20th Party Congress.”

[14] State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, China’s National Defense in the New Era (Beijing, July 2019).

[15] “Full Text of Xi Jinping’s Report to the 20th Party Congress.”

[16] “Xijinping zai shengbuji zhuyaolingdaoganbu jianchi dixian siwei zhe lifang fanhua jiezhongda fengxian zhuanti yantao bankai banshi shang fabiao zhongyao jianghua” [Xi Jinping Makes Important Speech at Opening Ceremony of Provincial and Ministerial-Level Major Leading Cadres’ Thematic Workshop on Persisting in Bottom-Line Thinking and Concentrating Efforts on Guarding Against, Resolving Major Risks], Xinhua, January 21, 2019.

[17] “Xi Calls for Guiding Healthy, High-Quality Development of Private Sector,” Xinhua, March 7, 2023.

[18] “Yi xijinping zongshuji zongti guojia anquanguan wei yinling puxie guojia Anquan xinpianzhang” [Take General Secretary Xi Jinping’s Overall National Security Concept as Guidance and Write a New Chapter of National Security], Qiushi, April 15, 2017.

[19] “Full Text of Xi Jinping’s Report to the 20th Party Congress.”

[20] Zhu Zheng, “Sixth Plenary Session Will Hold Great Significance in China’s History,” CGTN, November 8, 2021, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2021-11-08/Sixth-plenary-session-will-hold-great-significance-in-China-s-history-14ZPqjFr8Y0/index.html.