Since Xi Jinping became the general-secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the practices and logics of Chinese foreign policy have changed enormously. China’s ambitions are mostly global today and no longer limited to dominating only one region (such as the Asia-Pacific or Central Asia) or specific policy fields (such as technology or trade). Under Xi’s leadership, the party-state’s conception of its strategic space slowly accelerates into every place, space, and time of world politics. It underlines that what matters most to the CCP is the world’s growing compatibility with China, not vice versa. This endeavor will permanently transform the “geo” and “politics” of the next world order in ways that will at least in parts integrate Chinese ideas and norms.

In what follows, I briefly sketch out two major developments in Chinese foreign policy discourse that provide the framework for understanding China’s current geopolitical code. Geopolitical codes reflect strategic visions of order and space; they highlight how governments and political elites orientate themselves towards the world, and how this translates into conceptions of world order.

The Emergence of China’s Global Connectivity Politics

Connectivity is not a political term that Beijing prominently introduced, in the sense of a foreign policy goal or initiative. Rather, the decision to frame China’s foreign policy as global connectivity politics is based on an analysis of linguistic formulations that have developed and manifested themselves in the country’s foreign policy discourse. Diachronic text analysis shows that terms such as “neighborhood” are becoming less important after 2015, while other geographic categories such as “global” or “connectivity” are becoming more important. This is also reflected in the publication of the action plan for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), in which the geographic and cross-sectoral reach of the initiative is more strongly emphasized.1 Although BRI started as a rather limited transregional and mostly infrastructural initiative, it continued to unfold new realms of politics with far-reaching global ambitions and an emphasis on multidimensional as well as multiregional linkages. As I have analyzed elsewhere,2 BRI operates with manifold notions of geographic and functionalist space. It redefines the “geo,” and thus the political space, and indicates the importance of connectivity over integration.

China’s global connectivity politics has two very specific features. First, it has created a nexus of spatial structures (e.g., economic corridors, physical and digital ecosystems, transportation hubs, strategic support points, and other linkages) and different layers of technologies (e.g., telecommunication networks, digital payment systems, AI systems, global energy interconnections, energy production, and satellites) that could order the world in a different, China-centric way. Second, the Chinese government and a multiplicity of other Chinese actors are making these places of connectivity a strategic matter of geopolitics. Up until the Covid-19 pandemic, two dominant political principles characterized the shift in China’s foreign policy logic: docking (duijie) and discourse power (huayuquan).3 Prior to Xi, the discussion about bringing China in line with international norms and institutions was quite undecided. Since around 2015 or 2016, the principle of docking has replaced the Chinese domestic debate about political approaches of “integration into/merging with the international system.” To national audiences, the use of docking thus signals that the days of China’s passive integration are over. In this sense, docking defines the new direction of Chinese politics: less adjustment to international norms and practices, but proactive advertising of China’s own development path and modernization. For the foreign public, the difference between cooperation and docking is not always clear at first glance. After all, docking is also about a form of cooperation or connection between China and actors of the international system. However, docking establishes connectivity without requiring the Chinese side to first conform to international norms and conventions.

The docking principle changes Chinese foreign policy in two ways. First, it ends the discussions about China’s willingness to reform its political system before merging with the existing international system. Second, docking indicates China’s preference of a club governance approach. This builds on “China-plus” mechanisms in all sorts of contexts and especially with partners that also share the idea of building connectivity without a Western bias. Examples include the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, and the grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (or BRICS). Docking consequently underpins an approach of changing dominant norms, rules, and values by means of juxtaposition with new Chinese initiatives in order to create a global system more compatible with the CCP.

Under Xi, discourse power has gained in importance in both political and academic discourse. Using discourse power not only means introducing the CCP’s terminology on the international stage (e.g., BRI, community with a shared future of mankind, or inclusive multilateralism). It also is about reconfiguring all possible channels and places of politics, as well as changing the material reality of global governance by establishing new institutions and norms or expanding existing ones. In addition, Beijing often carefully considers which concepts of the Western liberal world order can be related to China’s international discourse system (guoji huayu tixi), highlighting that global knowledge production is no longer only limited to actors of the global North. For example, China sees the possibility to detach certain terms such as “community,” “development,” “inclusiveness,” “human rights,” “security,” or the “fight against deglobalization” from their inherent Western bias and aims to connect them with the CCP’s belief system. Such an approach suggests that Chinese actors, especially under Xi, are using dialogue mechanisms to manifest official CCP language globally.

China’s connectivity politics manifests a fundamental shift in the CCP leadership’s orientation toward the world. The major goal is to increase the compatibility of the world with China and the CCP—in other words, to integrate Chinese ideas and norms into the international system, while ultimately decreasing the impact of existing Western liberal rules and norms. While doing so, the Chinese leadership has established connectivity as a value in itself that, in contrast to liberal ideas of integration, does not preclude friction. China’s connectivity politics has slowly changed the underlying normative framework of cooperation but not necessarily the quantity of global connections. Put differently, connectivity does not define the nature of international relations; instead, it produces international relations that will not be peaceful (or violent) just because of connectivity. Today, the competition over connectivity gradually creates a new type of geopolitics that widens the playing field to all kinds of linkages, connections, or hubs and opens up the international space, particularly to the global South.

Framing the Next World Order: Development, Security, and Civilization

Prior to the pandemic, China’s global connectivity politics already represented the extension of Chinese ideas and practices to the international arena. This mostly happened under the framework of BRI, which expanded into all kinds of policy fields (e.g., energy, development, health, infrastructure, digital technology, and education) and to all world regions. The initiative linked most regional China-plus mechanisms with BRI and even aimed to connect BRI with parts of the United Nations—in particular, with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. China also signed countless bilateral memoranda of understanding with foreign governments and companies.

BRI has more or less evolved into a tool of global policymaking, producing different pieces that are indeed crucial to realize Xi Jinping’s vision of a community with a shared future of mankind—an international order less biased toward the West. But something has been missing: all pieces together have not automatically established an alternative to the fragmented world order (like a puzzle without boundaries). China’s ambitions and practices at times disrupted and openly challenged established actors, norms, and principles; they made cracks and frictions in the liberal international order visible, adding to the growing uncertainty and insecurity that characterize the current interregnum of world politics. However, China’s global connectivity politics lacked the systemic approach to build a frame that could define the context of world politics in the future. A couple of events triggered the CCP leadership to readjust its approach and focus much more systemically than before on transforming the international framework of politics. First, the pandemic isolated Chinese society and political elites from the Western world and had a lasting negative impact on China’s economic development. Second, the rivalry between the United States and China has only escalated under the Biden administration, induced by its decision to actively slow down China’s technological rise. Third, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has confirmed Beijing’s viewpoint of a growing Cold War mentality in international affairs caused by the United States and NATO.4

Against this backdrop, Xi has proposed three new initiatives that are to become the pillars of a China-inclusive world order: the Global Development Initiative (GDI), Global Security Initiative (GSI), and Global Civilization Initiative (GCI). The political direction of these three initiatives is already clear from the titles, which do not refer to China or introduce an unwieldy term such as “community with a shared future for mankind.”5 Instead, they are globally orientated, aiming to redefine the political, legal, and normative setting of international politics. In short, the three initiatives touch on different aspects of Xi’s vision.

Xi announced the GDI in September 2021 at the 76th session of the UN General Assembly. With the GDI, Chinese leaders aim to establish the strategic (and global) mechanism for a Chinese-led club promoting Chinese-style global development projects, while repurposing parts of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development with Chinese goals. They regard “development” as a key selling point to the world—in particular, to countries of the global South. This is deeply linked to China’s own experience as a developing country that has achieved certain socioeconomic successes over the years. But the GDI is also in line with China’s growing self-perception as a leading power of the global South and the world. It is an example of the new determination to transfer Chinese knowledge to the international arena.

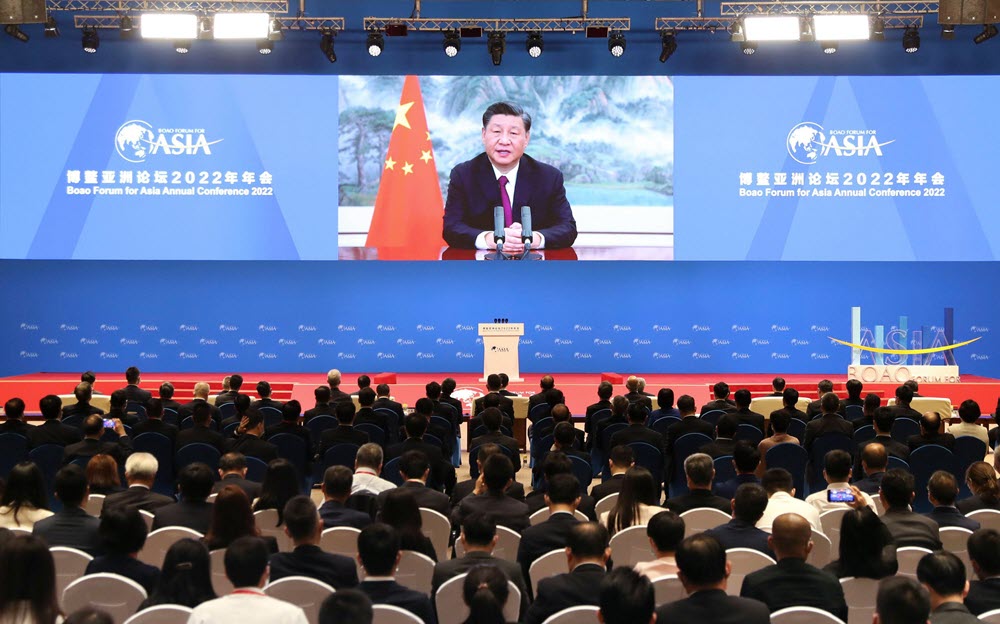

The GSI was introduced in April 2022 at the Boao Forum, and in February 2023 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs published a more detailed GSI concept paper. From a Chinese viewpoint, the initiative represents a reaction to the changing global security environment, which mainly coincides with the increasingly dangerous rivalry between China and the United States. Some Chinese experts point out that the Russian war in Ukraine marks Europe’s Zeitenwende, but China’s Zeitenwende is clearly linked to the country’s growing hostility with the United States, particularly after then president Donald Trump visited Xi in 2019.6 The GSI presents a Chinese vision of security reform for the UN system focusing on “indivisible security,” in contrast with the concept of “collective security” embodied by U.S.-led military alliances that China critiques as bloc politics and remnants of a Cold War mentality.7 The GSI also mentions certain places of regional insecurity (e.g., the Horn of Africa or Middle East) in which China might become more involved in the future. Still, the major goal lies in changing the international legal framework.

Hence, the GSI underscores a long-term vision in which the United States is at the core of the international security system. But it more importantly also presents a way to deal with the short-term reality of multipolarity in which some countries dominate security relations. The commitment to take “legitimate security concerns” (heli anquan guanche) of all countries seriously opens up ways to justify positions on security issues that are different from, and even opposed to, U.S. or Western perspectives. This Chinese view has been prominently put forward in the position paper on “political settlement of the Ukraine crisis.”8

Finally, at the CCP in Dialogue with World Political Parties High-Level Meeting, held in March 2023, Xi proposed the GCI, which officially highlights the tolerance and coexistence between all civilizations. In contrast with the narratives of “democracy vs. autocracy” or “Western universalism,” which are seen as exclusive for the rest of the world and in particular the global South, the GCI promotes a narrative of inclusiveness. Already in 2019, Xi rejected Samuel Huntington’s famous thesis of the “clash of civilizations”; instead, he highlighted that “various civilizations are not destined to clash.”9 Following this tradition, the GCI aims to create possibilities to exchange views about development and modernization paths with a strong focus on mutual learning, especially on the sub-governmental level. It opens the international space to other scales of governance and integrates them into China’s global portfolio. By offering training and education abroad, fostering ties among political parties, and strengthening exchanges between local communities, the Chinese leadership extends domestically gained knowledge to other countries while also increasing their dependence on China.

Conclusion

In this long period of transition from one world order to another, China’s politics of global connectivity, global development, global security, and global civilization represent the CCP’s view on how to organize the common space of international politics in the future. China’s geopolitical code highlights what type of spaces and actors are relevant to Beijing, and how Chinese leaders intend to rule them. It is designed to increase dependencies on China while at the same time decreasing the country’s dependencies on a U.S.-led liberal international order that is biased toward the West. China’s geopolitical vision thus raises questions about how European countries and the United States are preparing for a future order that will be at least partly characterized by Chinese ideas and conventions.

Nadine Godehardt is a Senior Associate at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin.

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

ENDNOTES

- In Xi’s first address to the UN General Assembly in 2015—the same year in which the BRI action plan was published—he highlighted the need to build a “new type of international relations” with the “community of shared future of mankind” at its core.

- For more comprehensive background, see Nadine Godehardt and Paul J. Kohlenberg, “China’s Global Connectivity Politics: A Meta-Geography in the Making,” in The Multidimensionality of Regions in World Politics, ed. Paul J. Kohlenberg and Nadine Godehardt (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021), 191–215. What follows is partly cited from Nadine Godehardt and Karoline Postel-Vinay, “Connectivity and Geopolitics: Beware the ‘New Wine in Old Bottles’ Approach,” SWP Comment, no. 35, July 2020.

- The aim is to decipher the logic of Chinese foreign policy under Xi. The focus is on the analysis of the central political principles and their respective direction of impact. It is of great importance to look at the political discourse in China, in terms of official formulations as well as academic debates. But the goal is less about providing a comprehensive description of the official discourse; rather, the underlying changes in conceptual prioritization are of interest.

- The ongoing impact on the global, and thus also Chinese, economy puts pressure on Beijing as well.

- Although a community with a shared future for mankind remains China’s foreign policy goal, the instruments have been adjusted and are now more systemic than symbolic.

- “Zeitenwende” was prominently reintroduced into the European political discourse by German chancellor Olaf Scholz in this policy statement on February 27, 2022, shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine: “We are living through a watershed era [Zeitenwende]. And that means that the world afterwards will no longer be the same as the world before.” See “Policy Statement by Olaf Scholz, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany and Member of the German Bundestag,” Bundesregierung, February 27, 2022, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/search/policy-statement-by-olaf-scholz-chancellor-of-the-federal-republic-of-germany-and-member-of-the-german-bundestag-27-february-2022-in-berlin-2008378.

- This issue was mentioned to the author by Chinese experts during a research stay in Beijing at the end of April 2023.

- This was also highlighted by Moritz Rudolf in testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Commission on May 4, 2023, available at https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2023-05/Moritz_Rudolf_Testimony.pdf. See Ministry of Foreign Affairs (PRC), “China’s Position on the Political Settlement of the Ukraine Crisis,” February 24, 2023, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/202302/t20230224_11030713.html.

- These remarks were given at the Conference on Dialogue of Asian Civilizations on May 15, 2019.