The first phase of the National Bureau of Asian Research’s Mapping China’s Strategic Space project concluded with two possible scenarios for the future of China’s strategic mental map.1 In the first, the extent of China’s strategic space would remain quasi-global, but Beijing would shift its attention to ideological expansion rather than costlier physical control of places and spaces. In the second scenario, factoring in the risk of overextension, especially at a time of slowing economic growth and increasing resource constraints, the geographic scope of China’s strategic space would be significantly reduced. In either of these scenarios, regardless of whether Beijing pursues maximalist aims or more modest expansion, the task of consolidating and shaping its strategic space closer to home would remain imperative. China’s “borderlands,” the geographic areas on either side of its physical boundaries, are the focus of this new phase of NBR’s multiyear research project.

Since November 2021, the Chinese government has included this proximate perimeter in its national security strategy under the label sanbian, or “three edges,” a contraction for China’s borderlands (or frontiers, bianjiang), borders (or border regions, bianjing), and periphery (or surrounding areas, zhoubian).2 Such an aggregation of the spaces located on either side of the dividing line separating the country from its neighbors, embracing both the areas within the outer rim of China’s national territory and those surrounding it, suggests that the Chinese leadership regards these spaces as deeply intermingled. This perspective not only links but also possibly melds territories that are under China’s control with those of its contiguous neighbors—the fourteen countries with which it shares a land border (North Korea, Russia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam) and six countries with which it shares or claims a maritime border (South Korea, Japan, the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia, and Indonesia). Moreover, the inclusion of the sanbian in China’s national security strategy, putting them at the same level as national sovereignty and territorial integrity, unquestionably reflects their utmost importance to the Chinese leadership.

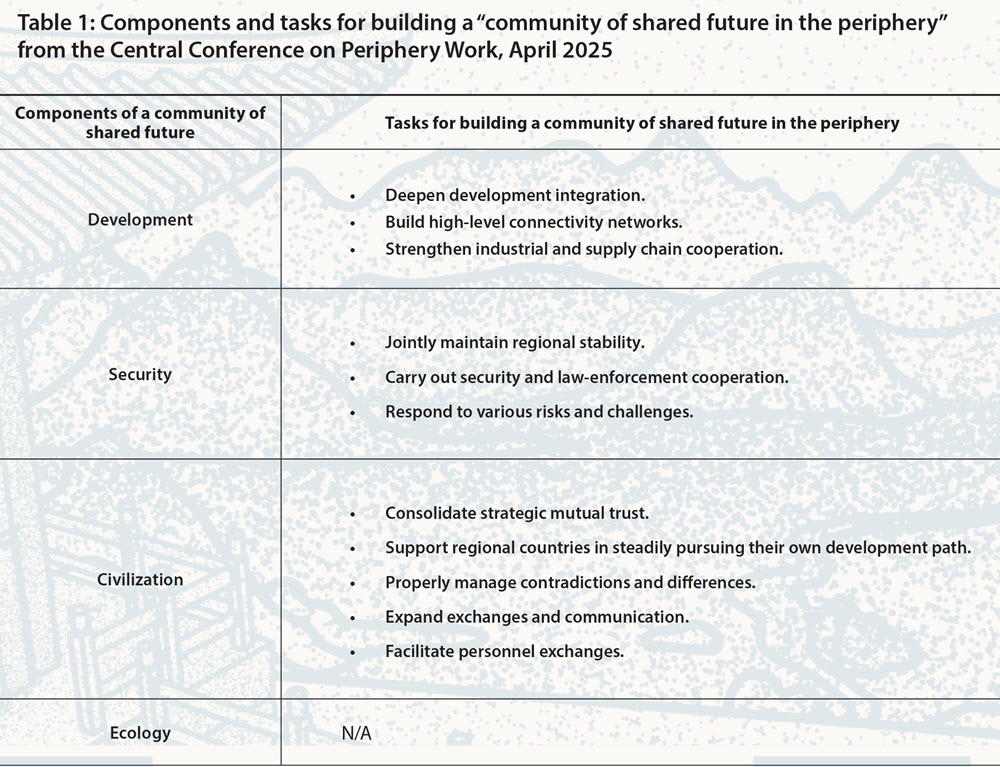

China’s diplomacy has traditionally considered the country’s surrounding neighborhood as a vital foundation for its development, security, and overall strategy. But under Xi Jinping, this wide area has been given even more dedicated attention. The unprecedented Central Conference on Periphery Diplomacy Work, convened in late October 2013, stressed the need for improving political and economic relations and establishing closer security cooperation with China’s neighbors in order to serve the cause of national rejuvenation.3 Twelve years later, in April 2025, the Central Conference on Periphery Work began with the self-congratulatory declaration that “at present, China’s relations with its neighbors are at the best level they have been in modern history.”4 The conference acknowledged how regional dynamics and global changes are deeply intertwined, an assessment that can be interpreted as the Chinese leadership’s recognition of the impending impact of the shift in the global balance of power on the decisions and choices of its neighbors. Setting the main direction for the party-state’s work toward China’s surrounding countries for the years ahead, Xi emphasized the need to “focus on building a community of shared future with the periphery and strive to create a new situation (xin jumian) in our periphery work.” Xi’s formulation signaled a shift toward a new approach aimed not just at cohabiting with China’s neighbors but at proactively giving shape to an entirely different regional order, one more aligned with Beijing’s own preferences and interests, and ultimately establishing a Chinese sphere of influence.5 The specific tasks listed to achieve this overall aim align with the components of the community of shared future, except for the “ecology” element (see Table 1).

A month earlier, at the March 2025 Two Sessions press conference, Foreign Minister Wang Yi declared that 17 regional countries had already endorsed the idea of joining the community of shared future, and that “two major clusters” (liangda jiqun) were emerging, one in Central Asia and the second on the Indochina peninsula. Wang highlighted the fact that China was the largest trading partner of 18 countries in Asia, and that 25 countries on its periphery had signed cooperation agreements related to the Belt and Road Initiative. Asia had become a “global development highland, an oasis of peace and stability,” while China was now the “center of gravity of Asia’s stability, the engine of its economic development, and the support of its security.”6

Notwithstanding the Chinese foreign minister’s positive report card, transforming the strategic space surrounding China will be a long-term endeavor. This task must begin at the hinges linking up the country to the outside world. As a crucial part of China’s strategic space, the borderland areas are considered as inherently contested, not just due to unresolved territorial disputes both on land and at sea, but also because of the ongoing great-power rivalry with the United States. Chinese elites believe that the periphery is the theater of choice for U.S. containment and suppression maneuvers, and that the kind of regional order that will emerge here will determine the competition’s overall outcome.7 The white paper on national security published in May 2025 describes the sanbian as areas where hostile foreign forces are stepping up their interference efforts, posing an increasing threat to China’s security.8

Has the Chinese leadership now come to the conclusion that, instead of tolerating such an unfavorable and threatening situation, the time has come to take action and push back? Instead of ceding terrain to its main adversary, must China now reclaim these spaces? Instead of its borderlands being infiltrated by hostile forces jeopardizing its core, should China use them in reverse as channels through which it can project its own influence and establish its own dominance? Some strategists speculate that China’s borderlands can become “pivotal gateways” connecting the country to its neighbors, the region, and beyond.9 Rather than being locked within its territorial margins, China can transform its borderlands into effective “capillaries” weaving cultural and economic exchanges with the countries on the other side of the border,10 spaces in which China’s power is both concentrated and able to “radiate” out.11 What does such an expansion look like, taking into consideration the many constraints in sight, including international law and China’s own strategic preferences? Which steps does it need to take? What instruments of statecraft should it use? Are some spaces, countries, or subregions to be prioritized over others?

Painting a comprehensive picture would require an investigation of China’s investment in and engagement over time with all twenty countries that constitute its immediate periphery across every dimension (economic, diplomatic, political, security, cultural). This is obviously a very large task that would require substantial time and resources. Instead, NBR’s Borderlands research project takes a more pointillist approach, examining a select set of cases to search for discernable patterns across issues and regions as well as identifying possible innovative models of expansion and probing China’s activities and modes of operation in the three domains that are currently officially highlighted as priorities (i.e., development, security, and civilization).

The Borderlands Dashboard, created in partnership with the AidData team at the College of William & Mary, uses over fifteen indicators across three domains—development, security, and civilization—to track the evolution of China’s engagement with its twenty contiguous neighbors since 2013. Written contributions by experts will explore topics such as the role Chinese provinces play in engaging with their near abroad, China’s use of infrastructure investments or economic coercion tools to influence its neighbors’ strategic decisions, its distinctive approach to cross-border crime, and China’s use of unusual instruments of statecraft to assert its dominance over its liquid borders. The resulting collection of essays will be accompanied by a series of audio documentaries that survey similar issues in parallel, illuminating the historical and current significance of China’s borderlands and traveling along China’s land and maritime borders in Russia’s shadow, in the Himalayas, along the Mekong River, and across the Yellow Sea.

China’s expansion does not occur in a vacuum. Each of its neighbors has the power to welcome, resist, or negotiate with China’s increasing presence. The Borderlands project will conclude with a series of in-region conferences—in Central, South, Southeast, and Northeast Asia—to engage in a dialogue with local scholars and gather on-the-ground perspectives.

NBR and Nadège Rolland are deeply grateful for the Carnegie Corporation of New York’s enthusiastic and generous support for the Borderlands project. We also would like to extend our appreciation to the AidData research lab at the College of William & Mary, including Samantha Custer, Bryan Burgess, John Custer, and Divya Mathew, for their outstanding work, friendly attitude, and infinite patience. We would further like to acknowledge the exceptional intellectual leadership and guidance of Ann Marie Murphy, Elizabeth Wishnick, and Daniel Markey, who have served as senior regional advisers to the project. Special thanks are also due to Alayna Bone, Jerome Siangco, Josh Ziemkowski, Sandra Ward, and Karolos Karnikis for their significant contributions and unrelenting efforts to make the project run smoothly.

Nadège Rolland is Distinguished Fellow for China Studies at the National Bureau of Asian Research.

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

ENDNOTES

- Nadège Rolland, “Mapping China’s Strategic Space,” National Bureau of Asian Research, NBR Special Report, no. 111, September 2024.

- “Zhonggong zhongyang zhengzhiju zhaokai huiyi shenyi ‘guojia anquan zhanlüe (2021–2025 nian)’ ‘jundui gongxun rongyu biaozhang tiaoli’ he ‘guojia keji zixun weiyuanhui 2021 nian zixun baogao’” [CCP Central Committee Politburo Holds Meeting to Review the “National Security Strategy (2021–2025),” the “Regulations on Military Merit and Honors,” and the “2021 Report of the National Science and Technology Advisory Committee”], Xinhua, November 18, 2021, http://cpc.people.com.cn/n1/2021/1118/c64094-32286177.html.

- “Xi Jinping zai zhoubian waijiao gongzuo zuotanhui shang fabiao zhongyao jianghua” [Xi Jinping Delivers Important Speech at the Conference on Periphery Diplomacy Work], Xinhua, October 25, 2013, http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2013-10/25/c_117878897.htm.

- “Zhongyang zhoubian gongzuo huiyi zai Beijing juxing Xi Jinping fabiao zhongyao jianghua” [Central Conference on Periphery Work Held in Beijing, Xi Jinping Delivers Important Speech], People’s Daily, April 9, 2025, http://politics.people.com.cn/n1/2025/0409/c1024-40456434.html.

- For a description of the community of shared future concept, see Nadège Rolland, “China’s Vision for a New World Order,” NBR, NBR Special Report, no. 83, January 2020, 36–40.

- “Wang Yi tan zhoubian waijiao: Jia he wanshi xing” [Wang Yi Talks about Periphery Diplomacy: When Family Lives in Harmony, Everything Prospers], Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), March 3, 2025, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/wjbzhd/202503/t20250307_11570176.shtml.

- See, for example, Zhang Jie, “Zhong Mei boyi xia de Zhongguo zhoubian Anquan huanjing: Yanjin dongle, zhuyao tezheng yu fazhan qushi” [China’s Periphery Security Environment in the Sino-U.S. Competition: Evolutionary Dynamics, Main Characteristics, and Development Trends], Asia-Pacific Security and Maritime Studies, no. 2 (2025); and Zhou Fangyin, “Zhongguo zhoubian anquan huanjing xin bianhua yu zhoubian waijiao celüe xuanze” [New Changes in China’s Periphery Security Environment and Diplomacy Choices in the Periphery], Contemporary World, no. 2 (2025).

- “Xin shidai de Zhongguo guojia Anquan baipishu” [White Paper on China’s National Security in the New Era], Ministry of National Defense (PRC), May 12, 2025, http://www.mod.gov.cn/gfbw/fgwx/bps/16385614.html.

- You Tianlong, “Reframing China Studies: Insights from the Margins and Global Intersections of China’s Borderlands,” China Perspectives, no. 139 (2024).

- Zhang Jie, “Fahui bianjiang diqu quwei youshi tuidong zhongguo changyi luodi zhoubian” [Taking Advantage of the Borderlands to Promote the Implementation of China’s Initiatives in the Periphery], Academy of Social Sciences, Special Issue, April 4, 2023.

- Hu Zhiding et al., “Zouxiang weida fuxing de Zhongguo diyuan zhanlüe: Guojia zhoubian lun” [China’s Geopolitical Strategy on the Way to the Great Rejuvenation: The National Neighborland Theory], World Regional Studies 30, no. 3 (2021).