Over the past two decades, economic sanctions have emerged as a central instrument in the foreign policy toolkit of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). As the most valuable export destination for many countries and a central hub in global supply chains for critical materials and intermediate inputs, China’s economy provides policymakers with a versatile foundation for statecraft. By imposing sanctions and restricting the ability of foreign governments, firms, or individuals to access the Chinese market, Beijing can compel, deter, or otherwise signal dissatisfaction with actors that cross its red lines.

This essay focuses specifically on economic coercion in the PRC’s borderlands: the twenty countries with which it shares land or maritime borders.1 Using a unique dataset of over two hundred economic restrictions imposed globally between 2010 and August 2025,2 we trace Beijing’s sanctioning behavior in the borderlands and argue that the region served as an important testing ground for Beijing’s initial sanction experimentation, especially through “informal” methods. That borderland countries served as proverbial canaries in a coal mine may be hardly surprising, given that geographic proximity means they are inherently more closely connected to, and therefore more likely to affect, interests of immediate importance to China like territory and borders. However, we also find that sanctioning activity in the PRC’s immediate neighborhood sharply declined after peaking in 2017. We argue that this is because Beijing has been driven to shift its focus toward using economic restrictions to counter pressure from more distant actors like the United States and members of the European Union.

Our analysis both illuminates the important role sanctions play in borderland politics and offers wider lessons about the role of sanctioning in China’s foreign economic policy globally. We illustrate how Beijing views economic statecraft as a means to shape the behavior of its neighbors and reveal the range of tools it has developed to do so. At the same time, a comparison of these approaches with the PRC’s global practices highlights some of the conditions and constraints that shape when and how Beijing chooses to apply economic coercion.

China’s Economic Sanctions

Once a relatively niche topic of interest to scholars of Chinese political economy,3 Beijing’s sanctions have been the subject of a growing number of policy reports and academic studies.4 While the small number of China sanctions in the early 2010s limited initial analysis to detailed case studies of one or a few episodes,5 a dramatic uptick in China’s sanctioning after 2016 generated sufficient data for researchers to recently begin conducting medium- and large-n studies.6 The larger datasets allow for the study of broader patterns in China’s use of coercive trade restrictions and their role in the country’s overall foreign policy approach, including which countries are being targeted, how such measures are deployed, and what kinds of political disputes are being engaged in.

Economic sanctions are measures imposed or coordinated by one state (often called the “sanctioner”) against economic actors from another state (often called the “target”), typically with a view to imposing coercive costs and causing behavioral change.7 Using such tools has often posed a dilemma for PRC policymakers. As the economy grew and other states came to rely more heavily on trade with China, it became increasingly viable—and perhaps tempting—for Beijing to use economic sticks to punish critics and exert coercive pressure that might help resolve international disputes in Beijing’s favor. Yet, as a historical target of sanctions itself, the PRC government has also long criticized their use as “hegemonic” and contrary to international law.8 Using sanctions would therefore leave Beijing open to charges of hypocrisy.

Navigating this apparent contradiction appears to have led PRC policymakers to develop a particular approach to sanctioning, in which economic restrictions are imposed in ways that leave the government leeway to plausibly deny any involvement. Rather than impose trade restrictions under official sanctions laws, Beijing has often opted for subtler methods. These include quietly directing customs authorities to hold up or refuse imports on grounds such as pest control, using domestic regulatory tools like antitrust provisions to obstruct foreign firms with operations on the mainland, or mobilizing consumer boycotts against multinational companies.9 As we detail below, China’s borderlands have served as the primary laboratory for this “informal” approach of implementing economic sanctions.

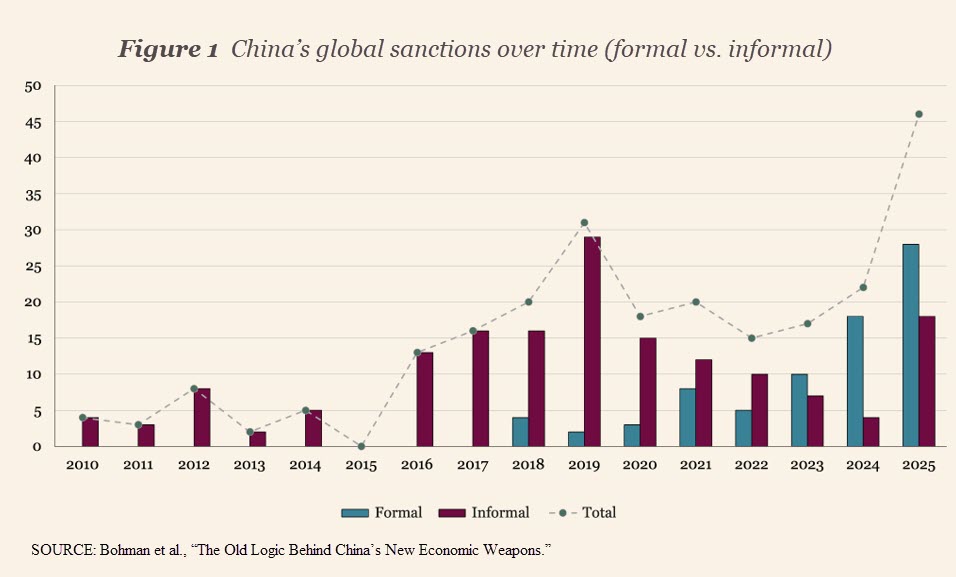

By the late 2010s, however, Chinese officials appeared to judge that their previous reliance on ad hoc and relatively discreet measures was no longer adequate. Facing more frequent economic clashes with the United States and other major powers, Beijing moved to establish new “formal” instruments for sanctioning, including the Unreliable Entity List, the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law, and an expanded export control regime.10 Since 2023, such formal sanctions have overtaken informal ones as China’s dominant method of implementation (see Figure 1). Unlike earlier informal practices, these tools are publicly announced and explicitly tied to political or security objectives in Chinese law. With them, the PRC began to take its sanctions from the borderlands to the wider world.

From the Borderlands to the World

When does Beijing sanction borderland countries and why? Like any other state, the PRC imposes sanctions selectively. Consistent with earlier research that has considered the factors that motivate PRC sanctions,11 our data suggests a relatively narrow range of triggers related to the regime’s three “core interests” of “domestic stability, sovereignty and territorial integrity, and social-economic development.”12 Approximately 42% of sanctions relate to issues concerning Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibet, or Xinjiang;13 9% relate to maritime territorial disputes; 18% relate to economic disputes in which the government perceives that foreign states have imposed sanctions or other discriminatory restrictions that constrain China’s growth; and the remaining 30% relate to other political disputes in which the PRC perceives its sovereignty, legitimacy, or other foreign policy interests to be challenged.14

Given the centrality of borders and other territorial issues to that mix of triggers, one might expect that much of China’s sanctioning would take place close to home. Two implications of the dataset stand out when we compare China’s sanctions against borderland countries with those targeting countries elsewhere in the world. First, the origins of China’s modern sanctioning behavior are indeed firmly grounded in its immediate neighborhood.15 Second, after a peak in 2017, the focus of China’s sanctioning activity has shifted decisively away from the borderlands (see Figure 2).16

The earliest sanctions on the borderlands targeted Japan. Following the Japanese government’s arrest of a Chinese trawler captain involved in a September 2010 maritime incident near the contested Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, China is widely alleged to have retaliated by imposing several restrictions on trade with Japan. Most notably, sanctions included limiting the export of rare earths. While the scope (or indeed existence) of these measures has been debated,17 research has shown that Japanese firms believed they were targeted, and this prompted industry and the Japanese government to collaborate on a series of initiatives to limit their reliance on Chinese rare earths.18 Following another flareup in the Senkaku/Diaoyu Island dispute in 2012, China again appeared to retaliate with economic restrictions.19

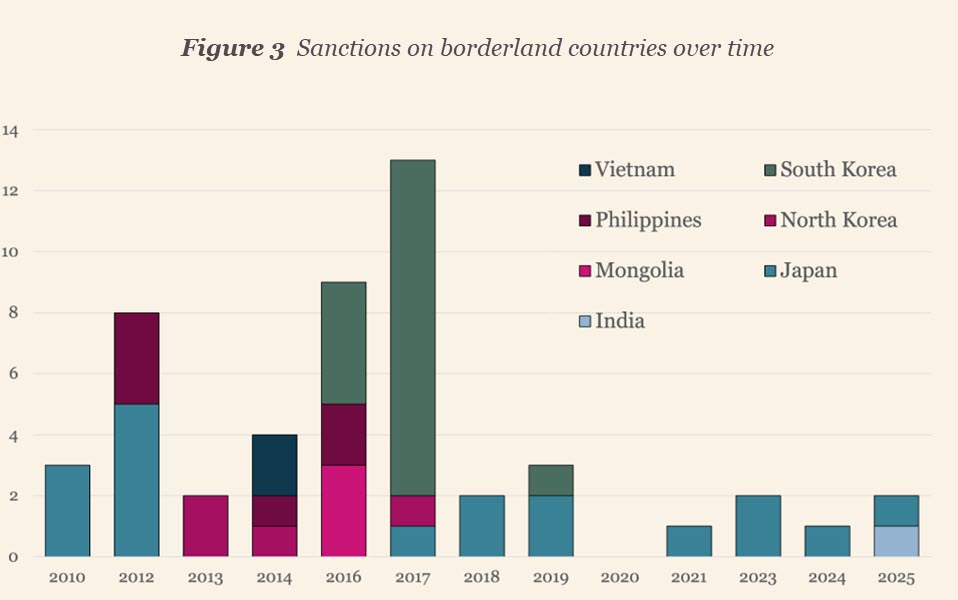

Maritime territorial disputes also have appeared to trigger China’s use of sanctions against neighbors in the South China Sea. In another widely studied case from 2012, Beijing restricted fruit imports and other trade with the Philippines following a standoff near the contested Scarborough Shoal.20 Restrictions were subsequently imposed on the Philippines when tensions flared up again in 2014 and 2016. Beijing was also alleged to limit trade with Vietnam following disagreements about a PRC oil rig deployed near the Paracel Islands in 2014 and against Mongolia after the Dalai Lama visited the country in November 2016. In all these cases, Beijing followed a similar playbook: targeting trade that was costly for neighboring countries to lose but relatively easy for China to substitute, imposing restrictions via discreet means, and at all times denying government responsibility for any irregularities in economic exchange.

That playbook was on full display in perhaps the most high-profile case to feature a borderland state: China’s response to South Korea’s joint deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile defense system with the United States. Beginning in 2016 and escalating over 2017 (see Figure 3), Beijing coordinated economic restrictions that affected a broad spectrum of South Korean industries and actors, ranging from tourism to Lotte department stores to electronic bidets.21 Only after the Moon Jae-in administration announced the so-called “three no’s” position in October 2017—no additional THAAD deployments, no participation in a U.S.-led missile defense network, and no trilateral military alliance with Japan and the United States—did China begin removing barriers.

Looking back, the effectiveness of China’s borderland sanctions by the end of 2017 appeared mixed.22 In most cases, Beijing had seemed to secure some plausible short-term concessions: Japan released the arrested boat captain, the Philippines lost access to Scarborough Shoal, Mongolia apologized and promised not to invite the Dalai Lama back, and South Korea committed to the three no’s. Causation, however, is debated due to issues such as timing and the fact that China typically deployed other instruments of statecraft, such as diplomatic and military signaling, alongside its trade restrictions.23 Moreover, some of the apparent tactical victories have begun to appear ephemeral. For example, initiatives to reduce reliance on the PRC market prompted by Japan’s experience were beginning to bear fruit, while the Philippines successfully challenged China’s territorial claims at the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

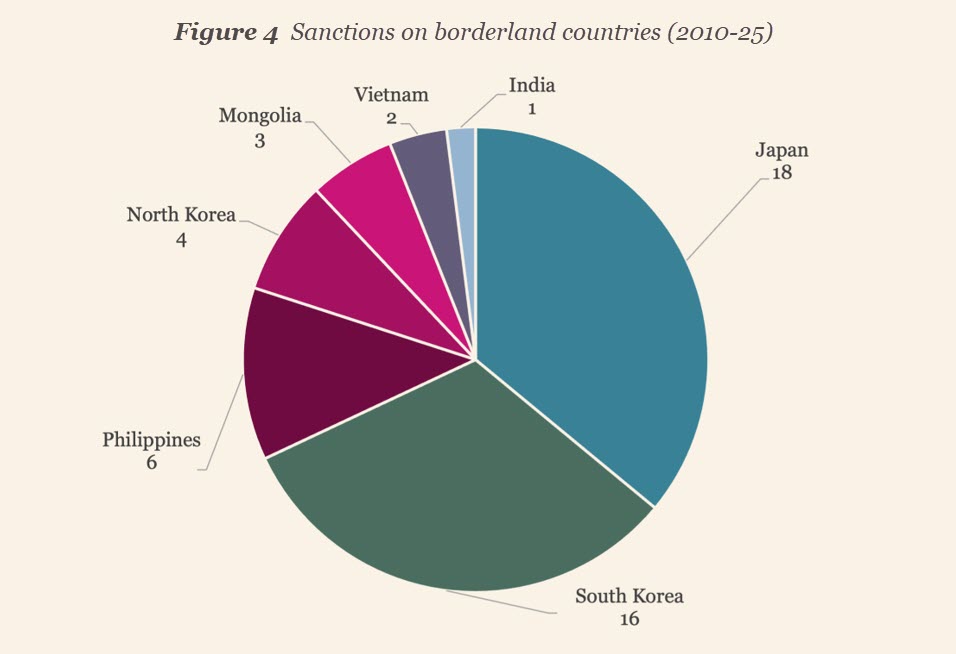

Yet, regardless of questions about effectiveness, what is clear is that borderland countries served as the primary testing ground as China developed strategies for implementing economic sanctions that it would subsequently take elsewhere and refine even further (see Figure 4). After the THAAD dispute, China’s sanctions against borderland states declined while its overall use of sanctions increased globally. The increase in this latter period can be attributed to two trends.

The first was a period in which, perhaps emboldened by the modest achievements of its borderland sanctioning, China deployed informal restrictions against a larger number of states in a wider range of circumstances. Notable episodes included a dispute with Canada sparked by the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou in December 2018, a dispute with Australia that began in early 2020 and ultimately saw Chinese restrictions on more than nine Australian export industries,24 and a spat with Lithuania that began after the July 2021 announcement that a new Taiwanese representative office would be established in Vilnius.25 As the number of China’s targets and the breadth of its imposed restrictions grew, however, the more they appeared to backfire. Notably, despite China’s vigorous efforts, neither Australia nor Lithuania offered clear concessions on the disputed issues, and growing international concern sparked a series of initiatives to address China’s sanctions, such as the G-7 Coordination Platform on Economic Coercion launched in May 2023.

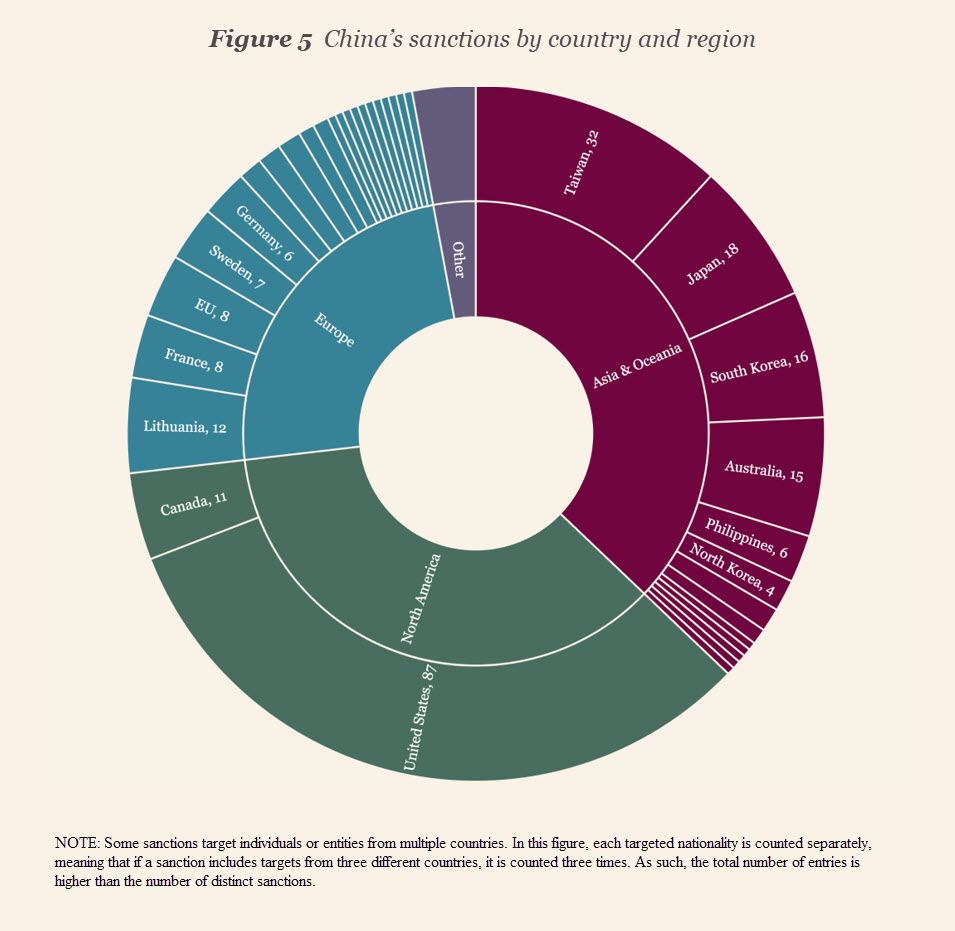

The second trend was the growing frequency with which China itself faced different types of foreign economic pressure. Beginning in 2018 with the first Trump administration’s trade war tariffs, China had to navigate an expanding range of trade restrictions. These included sanctions for its actions in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, foreign laws restricting market access for large Chinese firms like Huawei and ZTE, and export controls on advanced technologies (notably semiconductors and semiconductor equipment) imposed by the Biden and Trump administrations in coordination with U.S. allies. In order to respond to these measures effectively, China began to move beyond the somewhat clumsy informal sanctions frequently seen in the borderlands and started developing more precise, formal tools for retaliation.26 Those tools were then used with increasing frequency in a tit-for-tat fashion, overwhelmingly against the United States and the EU, such that the picture of China’s sanction targets has become much more global in scope (see Figure 5).

Interpreting the Rise and Fall of Borderland Sanctions

It is perhaps unsurprising that China experimented with economic sanctions on its neighbors first. Sheer proximity ensures that the borderlands intersect directly with the country’s vital interests, especially those tied to territory and national security. The gravity of geography also embedded neighboring states in China-centric trade networks early on, affording Beijing potential bargaining power. As such, the borderlands offered a logical starting place for testing and refining coercive economic instruments.

But why has China’s sanctioning of its borderlands declined since 2017? Analysts who have studied Xi Jinping’s speeches suggest that Beijing’s main goal with its neighbors is to ensure that these countries are as politically compliant as possible with the PRC and that they become increasingly economically dependent.27 As Xi put it in 2013, “We must strive to make our neighbors more friendly in politics, economically more closely tied to us, and we must have deeper security cooperation and closer people-to-people ties.”28 After early experiments with economic coercion in the borderlands, China may have concluded that sanctions were not the optimal method to achieve these aims. Evidence of backfiring sanctions, including Japan’s successful diversification and persistent defiance from countries like the Philippines and South Korea, could easily have contributed to a perception that sanctions undermined rather than promoted compliance and dependency, pushing Beijing to rely instead on other tools like diplomacy and gray-zone tactics (e.g., coast guard operations).

Another factor that likely contributed to Beijing’s apparently waning interest in sanctioning its neighbors is that China has become increasingly focused on its economic confrontation with the United States and U.S. allies. The onset of the first Trump administration marked a turning point, with wide-ranging economic restrictions imposed on Beijing and intensifying over time. While the pressure of foreign tariffs and export controls was mounting in the early 2020s, the efficacy of China’s sanctions also began to be called into question as they backfired in prominent cases. Under these circumstances, engaging in economic disputes simultaneously with borderland countries and the United States may have seemed imprudent. Rather than fight economic conflicts on multiple fronts, decision-makers may have opted to rely more on economic incentives and other tools of statecraft than on sanctions to influence neighbors.

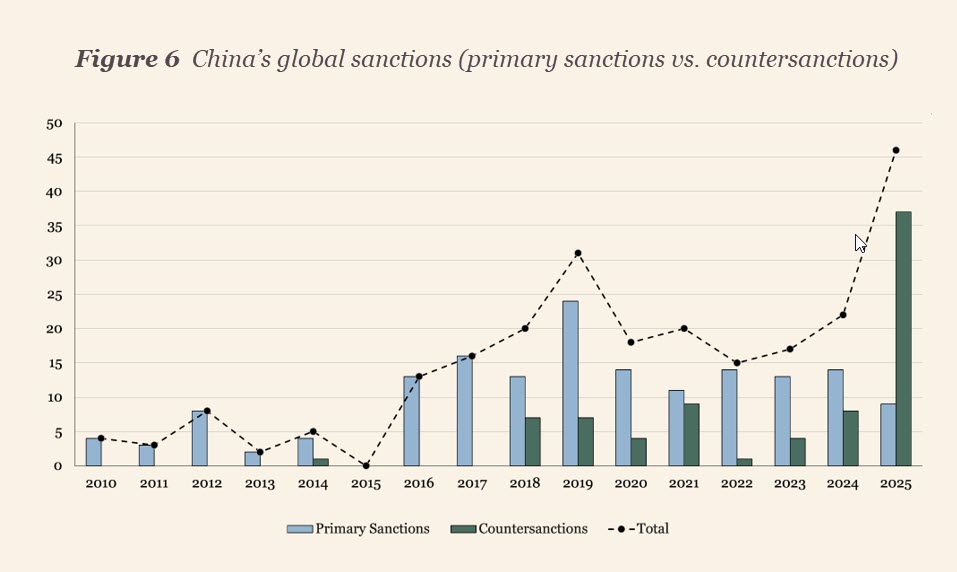

Moreover, as we have documented elsewhere, most of Beijing’s recent sanctions have been imposed as direct retaliation against foreign measures imposed on China—what we call “countersanctions.”29 These stand in contrast to “primary sanctions”—those where China has taken the initiative to impose restrictions in pursuit of broader political or security objectives such as silencing criticism or pressuring targets to reduce support for Taiwan (see Figure 6). Countersanctions have mainly targeted the United States and European governments in response to a growing range of sanctions, export controls, and tariffs they have imposed on China in recent years. By contrast, borderland states have only rarely imposed restrictive trade measures on China, and when they have, it has typically been under apparent pressure from Washington—such as Japanese export controls on advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment and technologies in 2023.30 Given this pattern, China’s shift toward countersanctions naturally reduces the incentives to sanction its borderland neighbors.

A notable corollary of this dynamic is that nearly all of China’s sanctions against the borderlands have been “informal.” This observation aligns with another broader pattern: China tends to impose formal sanctions primarily when directly retaliating against foreign measures (i.e., when countersanctioning), as such actions are more easily justified in the public sphere. The rise of China’s formal countersanctions has therefore coincided with a decline in borderland sanctions.

An alternative explanation for the decline in sanctions against the borderlands is that, contrary to widespread perceptions that China’s use of sanctions has been ineffective at compelling targets to change their behavior, it may have actually been a “secret success.”31 In this scenario, the use of sanctions in the borderlands may have declined not because China has become more cautious with sanctioning its neighbors but because its neighbors have been credibly deterred from engaging in behavior that triggers China’s use of sanctions in the first place—in other words, some “compliance” has already been achieved.

Evaluating this proposition poses significant challenges because it requires making assessments of unobservable counterfactuals regarding policy decisions that are already overdetermined. For example, no borderland states have received the Dalai Lama since Mongolia was punished in 2016.32 But if it were not for China’s sanctions, would the Dalai Lama’s visits have continued? Or consider the actions of borderland states with which China has maritime territorial disputes. Although clashes related to these disputes have continued (and in some cases increased) between Beijing and rival claimants since incidents in the early 2010s first triggered Chinese sanctions,33 sanctions have been used less. However, might actors like the Philippines or Japan have been even more assertive in asserting their claims in the South and East China Seas were it not for the threat of sanctions? Answering these questions with any precision is beyond the scope of this essay. We merely raise them to highlight the possibility that part of the explanation for the relative decline that we observe may be a product of borderland states more actively moderating their behavior to avoid triggering sanctions.

Regardless of the above, there is little reason to conclude that China’s recent restraint in imposing sanctions on borderland states will endure. While PRC sanctions officials have appeared to have their hands full devising responses to economic pressure from Washington and Brussels of late, neighboring countries are not necessarily in the clear. Beijing has continued to warn countries like Japan and South Korea that they, too, could be the subject of retaliatory measures if they support U.S. economic initiatives that disadvantage China.34 This dynamic is especially pronounced regarding export controls, where Beijing has introduced a new system to restrict the global supply of certain critical raw materials—some of which it dominates almost entirely. In another example of China’s innovative use of economic statecraft, Beijing recently obstructed the transfer of machinery, components, and technical managers in the electronics industry from the Chinese mainland to India, effectively slowing U.S. and European efforts to diversify supply chains.35 In October 2025, China sanctioned five subsidiaries of South Korean shipbuilder Hanwha, accusing them of supporting U.S. efforts to undermine PRC shipbuilding.36 Depending on where other borderland states are situated within supply chains, they could easily become implicated in similar dynamics going forward.

Ultimately, while Western pressure will not last forever, geography will. For China’s neighbors, proximity is permanent, and with it comes the certainty of disputes that flare up from time to time over territory or other regional matters. When Beijing eventually has more freedom to act, it may again be tempted to exercise its economic leverage in the borderlands. The question is not whether China will return to such practices, but when and in what form.

Victor A. Ferguson is an Assistant Professor at Hitotsubashi University’s Graduate School of Law and a Visiting Researcher at the University of Tokyo’s Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology.

Viking Bohman is a PhD candidate at Tufts University’s Fletcher School and an Associate Analyst at the Swedish National China Centre.

Audrye Wong is an Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Relations at the University of Southern California and Nonresident Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Note: The views and opinions expressed are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not represent the position of any government or organization.

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

ENDNOTES

- China shares a land border with fourteen countries (Afghanistan, Bhutan, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Vietnam) and shares or claims a maritime border with six (Brunei, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Philippines, and South Korea). See Nadège Rolland, “Borderlands: An Introduction,” National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR), July 28, 2025, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/borderlands-an-introduction. We do not discuss Taiwan because it falls outside the scope of this NBR series; however, we note that Taiwan has continued to be the target of a growing number of PRC sanctions.

- Viking Bohman, Audrye Wong, and Victor A. Ferguson, “The Old Logic Behind China’s New Economic Weapons,” Washington Quarterly 48, no. 3 (2025): 25–45. The dataset is available at https://chinasanctionsmonitor.com.

- See, for example, James Reilly, “China’s Unilateral Sanctions,” Washington Quarterly 35, no. 4 (2012): 121–33.

- See, for example, Emma M. Rafaelof et al., “Charting China’s Export Controls: Predicting Impacts on Critical U.S. Supply Chains,” NBR, NBR Special Report, no. 115, January 2025; Evan S. Medeiros and Andrew Polk, “China’s New Economic Weapons,” Washington Quarterly 48, no. 1 (2025): 99–123; and Viking Bohman, Audrye Wong, and Victor A. Ferguson, “China’s Sanctions Gambit: Formal and Informal Economic Coercion in the Second Trade War,” Swedish National China Centre, Brief, June 18, 2025, https://kinacentrum.se/en/publications/chinas-sanctions-gambit-formal-and-informal-economic-coercion-in-the-second-trade-war.

- See, for example, Xianwen Chen and Roberto Javier Garcia, “Economic Sanctions and Trade Diplomacy: Sanction-Busting Strategies, Market Distortion and Efficacy of China’s Restrictions on Norwegian Salmon Imports,” China Information 30, no. 1 (2016): 29–57; Angela Poh, “The Myth of Chinese Sanctions over South China Sea Disputes,” Washington Quarterly 40, no. 1 (2017): 143–65; and Eugene Gholz and Llewelyn Hughes, “Market Structure and Economic Sanctions: The 2010 Rare Earth Elements Episode as a Pathway Case of Market Adjustment,” Review of International Political Economy 28, no. 3 (2021): 611–34.

- See, for example, Jiakun Jack Zhang and Spencer Shanks, “Measuring Chinese Economic Sanctions 1949–2020: Introducing the China TIES Dataset,” Conflict Management and Peace Science 42, no. 3 (2025): 328–52; and Victor A. Ferguson, “Putting Your Money Where Your Mouth Is Not: China and Russia’s Implementation of Economic Sanctions,” Journal of Global Security Studies 10, no. 3 (2025).

- Sanctions may, however, be motivated by many other objectives, including signaling to domestic audiences or third parties and promoting the interests of specific constituencies in the sanctioner’s economy. See James M. Lindsay, “Trade Sanctions as Policy Instruments: A Re-examination,” International Studies Quarterly 30, no. 2 (1986): 153–73; and Elena V. McLean and Taehee Whang, “Designing Foreign Policy: Voters, Special Interest Groups, and Economic Sanctions,” Journal of Peace Research 51, no. 5 (2014): 589–602.

- See Yiying Xiong, “Legality, Legitimacy and Institutionalization: China’s Dilemma of Sanctions and Economic Coercion,” Journal of Contemporary China 34, no. 152 (2025): 181–97.

- See Ketian Vivian Zhang, “Just Do It: Explaining the Characteristics and Rationale of Chinese Economic Sanctions,” Texas National Security Review 7 (2024), https://tnsr.org/2024/06/just-do-it-explaining-the-characteristics-and-rationale-of-chinese-economic-sanctions; Audrye Wong, Leif-Eric Easley, and Hsin-wei Tang, “Mobilizing Patriotic Consumers: China’s New Strategy of Economic Coercion,” Journal of Strategic Studies 46, no. 6–7 (2023): 1287–1324; Viking Bohman and Hillevi Pårup, “Purchasing with the Party: Chinese Consumer Boycotts of Foreign Companies, 2008–2021,” Swedish National China Centre, Report, 2022; and Victor A. Ferguson, “Economic Lawfare: The Logic and Dynamics of Using Law to Exercise Economic Power,” International Studies Review 24, no. 3 (2022).

- Medeiros and Polk, “China’s New Economic Weapons.”

- See, for example, Taehee Whang and Wooyeal Paik, “Economic Sanctions by Non-democracies: A Study of Cases from China and Russia,” International Studies Quarterly 67, no. 4 (2023): sqad093.

- David C. Kang, Jackie S. H. Wong, and Zenobia T. Chan, “What Does China Want?” International Security 50, no. 1 (2025): 55.

- Examples of such issues include perceived foreign support for Taiwan, foreign governments reception of the Dalai Lama, or foreign criticism of Chinese policy in Xinjiang.

- Such disputes range from geopolitical concerns about the installation of missile-defense systems on the Korean Peninsula to perceived criticism of China’s treatment of human rights in response to the selection of Liu Xiaobo for the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize.

- Borderland states also feature prominently in the small number of cases recorded in datasets that cover 2000–2010. See Zhang, “Just Do It”; and Ferguson, “Putting Your Money Where Your Mouth Is Not.”

- As mentioned earlier, we do not discuss Taiwan here because it falls outside the scope of this NBR series; however, we note it has continued to be the target of a growing number of China’s economic sanctions. See Bohman et al., “The Old Logic Behind China’s New Economic Weapons.”

- See Alastair Iain Johnston, “How New and Assertive Is China’s New Assertiveness?” International Security 37, no. 4 (2013): 7–48; and Amy King and Shiro Armstrong, “Did China Really Ban Rare Earth Metals Exports to Japan?” East Asia Forum, August 18, 2013, https://eastasiaforum.org/2013/08/18/did-china-really-ban-rare-earth-metals-exports-to-japan.

- See Gholz and Hughes, “Market Structure and Economic Sanctions.”

- Xiaojun Li and Adam Y. Liu, “Business as Usual? Economic Responses to Political Tensions between China and Japan,” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 19, no. 2 (2019): 213–36.

- These restrictions are also debated. See Poh, “The Myth of Chinese Sanctions”; and Zhang, “Just Do It.”

- See Darren J. Lim and Victor A. Ferguson, “Informal Economic Sanctions: The Political Economy of Chinese Coercion during the THAAD Dispute,” Review of International Political Economy 29, no. 5 (2022): 1525–48; and Kacie Miura, “To Punish or Protect? Local Leaders and Economic Coercion in China,” International Security 48, no. 2 (2023): 127–63.

- We acknowledge the complexity of evaluating the “success” of sanctions, which is well beyond the scope of this essay.

- For the Japan 2010 case, for example, see Keisuke Iida, Japan’s Security and Economic Dependence on China and the United States: Cool Politics, Lukewarm Economics (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017), chap. 3. A useful, concise assessment of outcomes in each of the cases is presented in Matthew Reynolds and Matthew P. Goodman, “Deny, Deflect, Deter: Countering China’s Economic Coercion,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Report, March 2023.

- See Victor A. Ferguson, Scott Waldron, and Darren J. Lim, “Market Adjustments to Import Sanctions: Lessons from Chinese Restrictions on Australian Trade, 2020–21,” Review of International Political Economy 30, no. 4 (2023): 1255–81.

- See Verónica Fraile del Álamo and Darren J. Lim, “Supply Chain Secondary Sanctions,” Law and Geoeconomics 1, no. 1 (2025): 110–40.

- See Medeiros and Polk, “China’s New Economic Weapons.”

- Kevin Rudd, On Xi Jinping: How Xi’s Marxist Nationalism Is Shaping China and the World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024).

- “Xi Jinping: China to Further Friendly Relations with Neighboring Countries,” Xinhua, October 26, 2013, https://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/china//2013-10/26/content_17060905_2.htm.

- Bohman et al., “The Old Logic Behind China’s New Economic Weapons.”

- See, for example, Gregory C. Allen, Emily Benson, and Margot Putnam, “Japan and the Netherlands Announce Plans for New Export Controls on Semiconductor Equipment,” CSIS, April 10, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/japan-and-netherlands-announce-plans-new-export-controls-semiconductor-equipment.

- Nicholas L. Miller, “The Secret Success of Nonproliferation Sanctions,” International Organization 68, no. 4 (2014): 913–44. For an example of work that argues that China’s sanctions have had a deterrent effect on target behavior, see Naoise McDonagh and Sascha-Dominik Dov Bachmann, “Economic Coercion and Grey Zone Competition: Reassessing the China-Australia Case,” Pacific Affairs 98, no. 1 (2025): 53–77.

- On the link between the Dalai Lama and China’s sanctioning, see Andreas Fuchs and Nils-Hendrik Klann, “Paying a Visit: The Dalai Lama Effect on International Trade,” Journal of international economics 91, no. 1 (2013): 164–77; and Ketian Zhang, China’s Gambit: The Calculus of Coercion (Cambridge University Press, 2024), 162–88.

- See H.K.T. Nguyen, “Mapping a Decade of Disputant and Non-disputant Behaviors in the South China Sea Dispute,” Marine Policy 165 (2024): 106189; Zhang, China’s Gambit, 53; and Andrew Chubb, “Dynamics of Assertiveness in the South China Sea: China, the Philippines, and Vietnam, 1970–2015,” NBR, NBR Special Report, no. 99, May 2022.

- “China Asks Korea Not to Supply Products Using Rare Earths to U.S. Defence Firms, Paper Reports,” Reuters, April 22, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/china-asks-korea-not-export-products-using-rare-earths-us-defense-firms-paper-2025-04-22; Jenny Leonard, Mackenzie Hawkins, and Takashi Mochizuki, “China Warns Japan of Retaliation for Possible New Chip Curbs,” Bloomberg, September 2, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-09-02/china-warns-japan-of-retaliation-over-potential-new-chip-curbs; and Nectar Gan, “Beijing Warns Countries against Colluding with U.S. to Restrict Trade with China,” CNN, April 21, 2025, https://www.cnn.com/2025/04/20/business/china-warns-countries-us-trade-war-intl-hnk.

- Ryan McMorrow et al., “China Tightens Grip on Tech, Minerals and Engineers as Trade War Spirals,” Financial Times, February 15, 2025, https://www.ft.com/content/d48e9a90-ba6a-42bb-9da7-58db89643f86.

- “China Slaps Sanctions on Korean Shipbuilder Accused of Helping U.S.,” Financial Times, October 14, 2025, https://www.ft.com/content/f8255bd7-a9ae-4a97-bcab-b79efdc02897.