The global scope of China’s geostrategic ambitions has become more obvious since Xi Jinping’s accession to power. However, expansionist inclinations first became evident in national security and military circles as early as the mid-1980s. Since that period, Chinese strategic thinkers have been mulling over the dimensions of an enlarged space, deemed necessary to ensure China’s survival. The expansion of this imagined space coincides with the growth of China’s national power and perceptions of global power shifts. Propelled by the fading of the Soviet threat and by the country’s transformation into a world-class economic power, China’s definition of its strategic space expanded dramatically, reaching a truly global scale around 2012.

Heavily influenced by classical geopolitics, the imagined space strategic elites believe they need for their country’s “survival and growth” is much larger than is commonly acknowledged. It extends far beyond the fictional nine-dash line and encompasses more even than the territories lost with the collapse of the Qing Dynasty.

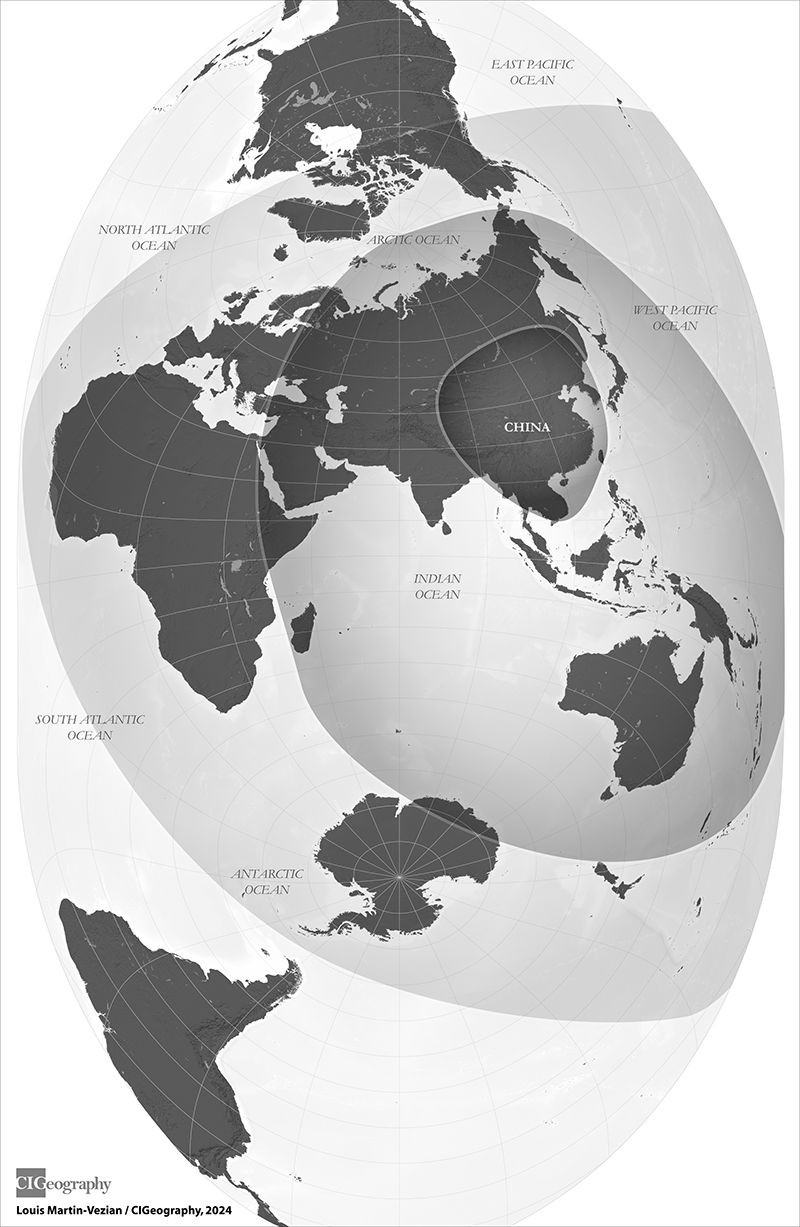

China’s strategic space embraces a vast continental and maritime expanse—a “pan-Eurasian continent” that includes Eurasia (Southeast, South, Central, and West Asia), extending outward toward Western Europe and Africa, as well as its adjacent waters (the South Pacific, Indian Ocean, and Arctic and Antarctic Oceans, and expanding all the way to the Atlantic Ocean). This strategic space is construed not simply as a military area of responsibility but as a realm in which China must exercise a degree of authority translating into both tangible control and intangible influence.

- The global pandemic, Russia’s war against Ukraine, and China’s most recent economic slowdown do not seem to have affected the Chinese elites’ assessment that their country’s power continues to grow relative to that of the United States. At the same time, they may already be facing the prospect of overextension, possibly leading to a revision of their conception of strategic space.

- China’s strategic space is assumed to be inherently contested. Chinese elites see expansion as the natural result of their country’s growing power and interests. At the same time, they recognize the inevitability of external pushback and efforts to contain this expansion. The risk of confrontation or even conflict, especially in what China defines as “strategic new frontiers,” should not be overlooked. The Eurasian continent and its surrounding oceans are crucial, as is the linkage between China’s and Russia’s strategic spaces. China’s maritime and global expansion would not have been possible and could not be sustainable without a secure continental rear area.

- Finally, the further expansion of China’s strategic space might not materialize in the same ways as in previous historical periods, but the exact form that it will take is still unclear at this stage. In a 21st-century context, it is unrealistic to imagine the military conquest of multiple foreign territories across such a vast expanse, similar to the growth of the Roman empire, European colonialism, Japan’s coprosperity sphere, or German Lebensraum (living space). Other tools, including economic and ideological, may be preferred to secure the space that China’s strategists believe is essential to national prosperity and survival.

Nadège Rolland is Distinguished Fellow for China Studies at the National Bureau of Asian Research. Her NBR publications include China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative (2017), “China’s Vision for a New World Order” (2020), and “A New Great Game? Situating Africa in China’s Strategic Thinking” (2021).

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.