With an increasingly powerful People’s Republic of China (PRC) under paramount leader Xi Jinping engaging in meteoric military-maritime buildup and pressing disputed sovereignty claims with increasing assertiveness, it is more important than ever to consider Beijing’s “mental map”: how its leaders regard the physical nature of strategic space. As Andrew Rhodes argues cogently, “Being able to ‘think in space’ is a crucial tool for decision-makers, but one that is often deemphasized.”1 This applies to understanding both how PRC leaders envision China’s strategic space and how it is evolving in practice.

Beijing pursues a disciplined hierarchy of national security priorities in a pattern that Peter Dutton terms “concentrism”: “The strongest power is reserved for managing and securing its periphery, the next ring is a zone of disruption of potential attacking powers, and the third is to venture beyond the first two largely at the sufferance of stronger regional powers.” He refers to these three spheres, respectively, as “zones of control, influence, and reach.”2 The resulting “ripples of capability” in China’s military forces, extending in progressively descending circles of intensity outward from PRC shores, remain best viewed overall “through the lens of distance.”3

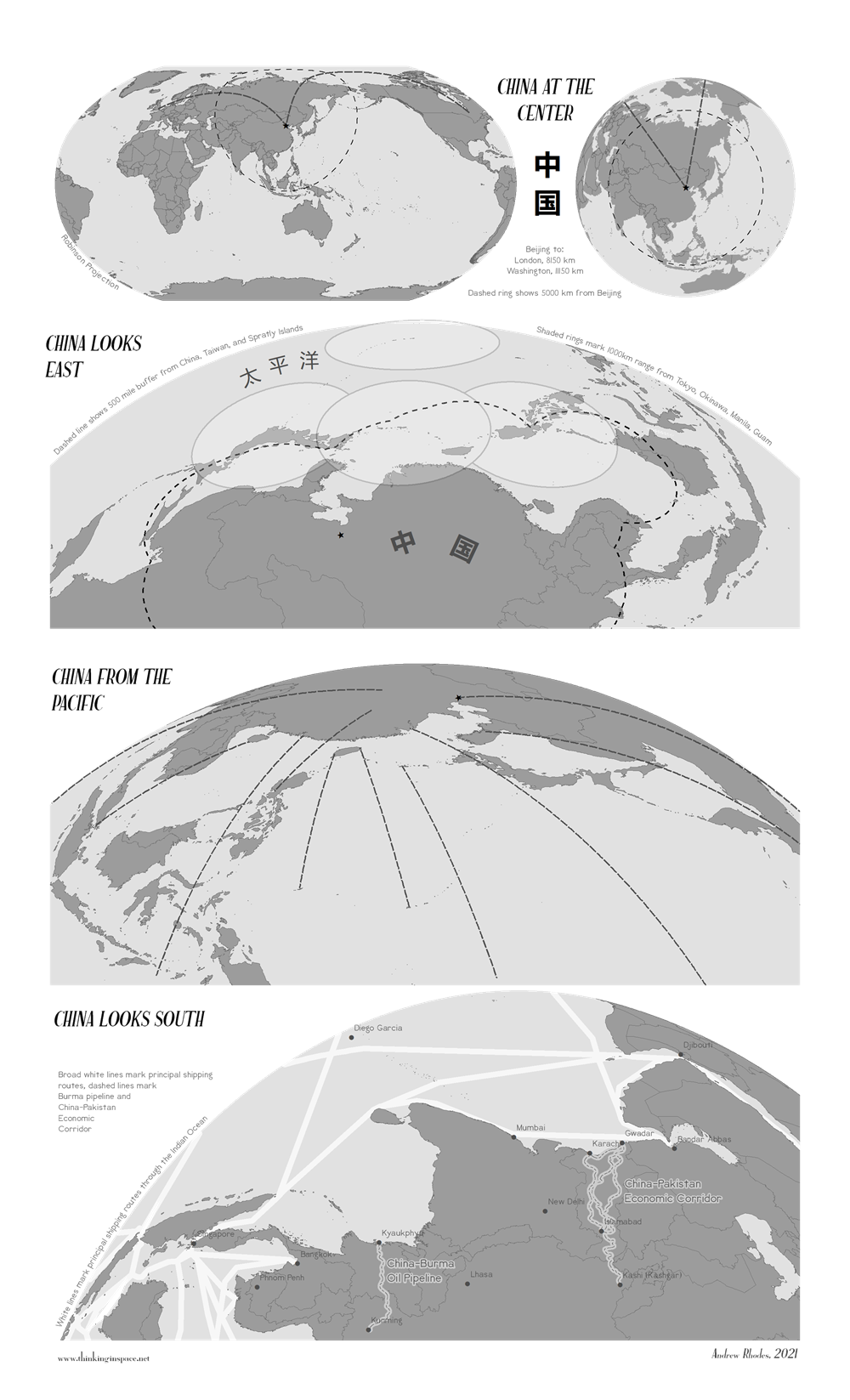

Per the mental map of Xi and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) the PRC has achieved relatively smooth expansion of influence overland through Central Asia to Europe and the Middle East. It is still working on a more contested project of maritime expansion but has made considerable progress there as well. Beijing’s ambitions also extend to frontier domains. Regarding the projection of sea power, China faces difficult opponents and geography. It is nevertheless becoming an increasingly formidable opponent to neighbors over sovereignty disputes, none more so than Taiwan. The map below by Rhodes offers perspectives on Beijing’s geostrategic location.

History and Geography

The PRC’s consistent, incremental security priorities draw on historical and spatial fundamentals.4 The CCP has followed the precedent of dynastic China in expanding along relatively predictable geophysical lines, but it has done so with unprecedented focus and determination, which has thus far yielded steady, substantive progress. Party-army capture of the Chinese state in 1949 set the stage for achieving the next layer of security: party-state administration of core historic heartland. Next came control of ethno-religious minority borderlands, with Tibet being invaded in 1950 and subjugated the following year. China then spent much of the Cold War defending the integrity of its self-defined land borders. In 1962, it defeated India in a border conflict. In 1969, PRC forces preemptively attacked Soviet counterparts on the Ussuri River’s contested Zhenbao Island to deter broader incursions by thousands of Soviet troops deployed along China’s disputed northern border. In 1979, China waged a bloody border war to punish Vietnam for invading Cambodia and deposing the Khmer Rouge. This conflict was followed by years of episodic skirmishes.

Meanwhile, China’s seaboard faced important flashpoints unresolved by civil war. In 1950, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) captured Hainan Island and subsequently secured the mainland coastline and airspace by limiting and ultimately halting Kuomintang coastal raids, harassment, and subsequently U.S.-sponsored U-2 overflights.5

However, it failed to wrest the heavily fortified offshore islands of Kinmen and Matsu from Kuomintang control, shelling them intermittently instead. Following the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Mao Zedong indefinitely postponed an invasion of Taiwan slated for 1950–51. Taiwan Strait crises erupted in 1954–55, 1958, and 1995–96. Today, a Taiwan contingency is the PLA’s lead planning scenario. China’s military strategies of 1993, 2004, and 2014 focus geographically on Taiwan and its surroundings and emphasize achieving the sophistication necessary to prevail in a contingency potentially involving the U.S. military.

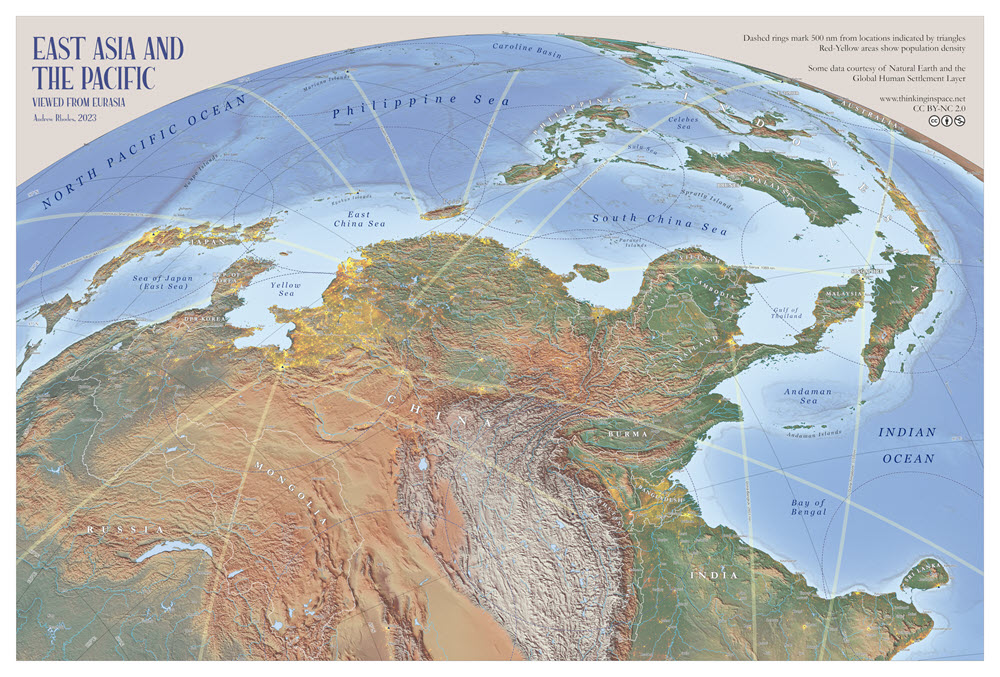

History and geography still matter today. Although China has now settled its land border disputes with all neighbors save India and Bhutan, its achievements in the maritime domain are mixed. Leaders under Xi Jinping regard extensive outstanding claims in the “near seas”—the Yellow, East China, and South China Seas—as historical injustices that must ultimately be rectified, thereby demonstrating the CCP’s unique ability to reclaim China’s rightful place. Beijing has the world’s most numerous, extensive disputed island/feature claims, with the largest number of counterparties. Foremost among these unresolved sovereignty issues is whether Xi can achieve his goal of bringing Taiwan under CCP control within his time in power.

This is a question of tremendous import for the world, the region, and the PRC’s future strategic space. It also highlights the direction of Beijing’s thinking. PRC defense white papers and the “main strategic direction” of the PLA’s doctrine codify a focus on the southeast maritime direction. Standard wall maps in the PRC understandably center on China, with key geopolitical rivalry extending across the Pacific and various economic interests and ties snaking westward across Eurasia. The map below by Rhodes captures the world as it looks from Beijing out to the disputed southeastern seaboard and beyond.

Even China’s third sea force (after its navy and coast guard), the Maritime Militia, is an integral part of the country’s armed forces with critical peacetime and wartime roles, including in a potential cross-strait amphibious invasion. All three sea forces are the world’s largest by number of ships. This seaward surge reflects the confluence of strategic fundaments, the enduring shaping power of geography, and geohistorical implications. Powered by the world’s second-largest economy and defense budget, China has gone to sea with scale, sophistication, and sea power components that no continental country previously sustained in modernity. They are supplied by the world’s largest shipyard infrastructure, yielding the fastest expansion of production capacity and largest military buildup since World War II.

On the civilian side of China’s sprawling waterfront, sea power is supplemented by the world’s largest fishing fleet by number of vessels and fishers, commercial fleet by shipping capacity, merchant marine, and marine economy overall. China also boasts a large nationally flagged tanker fleet and globe-girdling port infrastructure. Xi, living out previous generations’ dreams to truly develop the “blue economy,”6 is personally guiding China’s transformation into a comprehensive “great maritime power.”7 Awe-inspiring high-seas capabilities should dispel any remaining illusions that China is a hidebound continental power paying lip service to maritime affairs.

China’s Evolving Maritime Geography

For all this progress, comparing and contrasting PRC military strategies and capabilities as they apply to the “near seas” versus the “far seas,” the airspace above, and the related and supporting capabilities in other domains reveals persistent gradients. PRC naval strategy and attendant changes in warfare area capabilities have evolved over successive eras, with greater responsibilities in each new phase adding a new layer to the previous core.8 While the innermost core of “near seas active defense,” established in 1985, retains priority, Xi Jinping added a “far seas protection” strategy in 2015. Moreover, since around 2019 the PLA Navy has pursued an emerging combination of “near seas defense, far seas protection, [global] oceanic presence, and expansion into the two poles.”9

Already China and its military have achieved a status and confidence unseen in nearly two centuries and unprecedented in sophistication and geographic scope—going, literally and figuratively, where elements of Chinese state power never went before. This enables production and projection of military power in unprecedented ways. The extent to which China can deliver force sustainably over increasing distances to further its burgeoning interests is one of the key questions of 21st-century geopolitics—with major consequences for Beijing’s role and footprint in the world and for U.S. and allied interests.

Here, as in so many areas, much depends on topic and framing. As a consequential leader taking China in a more determined and dangerous (for neighbors, the United States, and other potential opponents) direction with regard to military issues than his post-Mao predecessors did, or a baseline alternative paramount leader likely would, Xi himself matters significantly. China’s first navalist leader, having in 2018 called for a “world-class navy,”10 he is a personalist strongman pursuing a personality cult and historical legacy in the same league as that which Mao attained before the Cultural Revolution. All these factors drive China harder and faster in military maritime development than they would have without Xi.11

Geographic constraints still matter, but somewhat less, and differently. They are not static and unchallenged: how they manifest, and to what extent, evolves constantly. One significant source of change is geoengineering. Long ago, constructing the Great Wall and Grand Canal fundamentally reshaped Chinese strategic space, with maritime implications.12 Under Xi, China in 2014 began engineering an extraordinary externalization of its coastal defense posture through extreme augmentation and fortification of features it occupies in the South China Sea. Similarly impactful is the country’s growing presence in a vast network of PRC-developed and -funded ports, including some offering naval access. China’s establishment of its first overseas military facility in Djibouti has been followed quietly in Ream, Cambodia, with a portfolio of other locations under consideration.

Since the Cold War, the Pacific Islands have evolved for China as barriers, springboards, benchmarks, and now vectors of influence and disruption of U.S. power projection. Acute Pacific land scarcity makes these “chains” of islands encircling the Eurasian landmass strategically pivotal for great powers contending for mastery over the region. While imperial Japan and Germany had strategic conceptions in this regard, it was Douglas MacArthur who formally linked the “chain of islands” to U.S. constraint of Communist hostility.13 A decade ago, Du Wenlong, a senior researcher at the PLA Academy of Military Science, declared the PRC’s success in escaping such strategic confinement: “The Chinese navy has the capability to cut the first island chain into several pieces. Now the chain is fragmented.”14

In 1921, Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel “Pete” Ellis observed that the area east of what PRC strategists subsequently termed the second island chain, traversing Guam and the Marshall, Caroline, and Palau Islands, formed “a ‘cloud’ of islands stretching east and west.”15 Just as PRC strategists discovered and repurposed island chains as China became able to project power out to, and then through, them, PRC strategists may well embrace an even broader “second island cloud” concept as PRC activities vis-à-vis Pacific Island countries increase and diversify. Rhodes’s map below offers a decided improvement over the truncated island chain maps in the Pentagon’s annual reports on China’s military power and a fitting supplement to the PLA Navy’s more extensive tracing of these strategic features.16

Beyond the island chains, the PRC’s geographic weightings defy enduring precision. A leading 2013 publication contains a section on the need to “expand [China’s] strategic space.”17 A subsection advocates a subsequent layer of PLA Navy emphases: “expanding to the two oceans” (the Pacific and Indian) as well as adjoining littoral regions, a preponderance of global water space akin to the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command’s vast jurisdiction.18 It also mentions the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and Arctic Ocean.19 This Indo-Pacific construct subsequently faded from official documents but endures in some serious sources. “The Pacific Ocean issue is the key to whether China’s maritime territorial rights and interests can be secured,” a 2020 article advocating a “two ocean strategy” maintains, “while the Indian Ocean is more about being the transportation artery for the development of China’s economy and production.”20

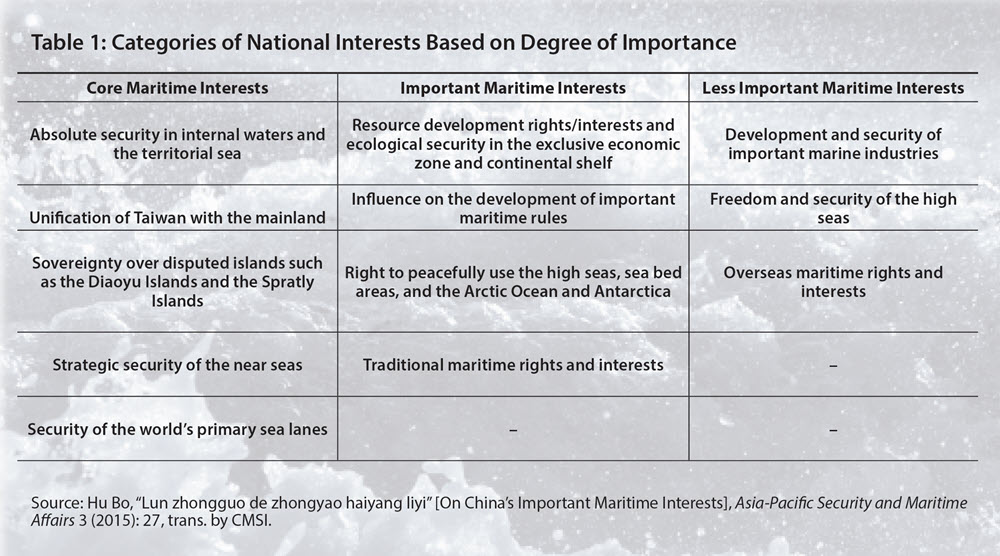

Hu Bo, a scholar at Peking University, articulates a “hierarchy of national interests” far more systematically than the PRC’s intentionally vague official statements. As his matrix presented in the table below illustrates, however, overlapping priorities resist clear-cut geographic demarcation.

Overall, available PRC writings suggest a tentative prioritization of maritime spheres: (1) near seas and first island chain, (2) waters out to the second island chain, (3) the western Pacific out to a third island chain bisecting Hawaii and the northern Indian Ocean, (4) the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and Arctic Ocean, and (5) beyond. Few sources explicitly delineate such layers, but few, if any, disagree.21

Additionally, Beijing may advance dramatically in “new strategic frontiers,” where it enjoys particular room for maneuver as rival powers struggle to invest the requisite resources to compete in less-established areas featuring extreme conditions. China is already attempting to achieve a more comprehensive, active presence globally, including in geophysically extreme zones of particular importance, such as sea depths and the seabed, outer space, and the Arctic and Antarctic. Major General Xiao Tianliang emphasizes that “the view of time and space in war has undergone profound changes…the battlespace is expanding rapidly…. Space and cyberspace have become new commanding heights of military competition.”22 The map below projects Beijing’s maritime priorities geographically. It illustrates the aforementioned maritime strategic zones and offers the best official depiction available of key Maritime Silk Road sea lanes in Xi’s BRI.23 It also plots the PLA Navy’s current bases as well as potential future first-priority and second-priority ports that might conceivably offer special access and support.24

Constraints on China’s Power in the Maritime Domain

China is developing capabilities to project power globally and throughout emerging domains. It does so multifariously, including through enhanced overseas presence and activities in order to secure citizens, assets, and access to material resources while attempting to circumvent or neutralize chokepoints. Beijing may well make considerably greater strides worldwide and muster forces with robust global influence and reach. Indeed, Xi’s call for a “world-class navy” by 2049 demands no less.

However, China’s geography and political system impose an unusually severe power-distance (“loss of strength”) gradient. Radiation out into contested spaces and domains increases reliance on vulnerable land facilities, other fixed support points, and concentrated platforms such as carriers. China’s homeland supports a dense network of potent counter-intervention capabilities, but the intensity with which it is incentivized and able to project military power attenuates markedly with distance from shore. Beijing has progressively less reason to project power maximally at longer ranges, particularly under potentially contested conditions.

In the maritime domain, in particular, chokepoints and barriers—many with proximate U.S., allied, and partner military facilities and presence—are another hindrance to China projecting peak power even farther from its shores. Analysts at the PLA Naval Research Institute acknowledge that, “according to the law of diminishing marginal utility, the strategic power that Chinese sea power can exert in the Indian Ocean is extremely limited.” Moreover, “the sea routes by which China can enter the Indian Ocean are extremely narrow: China must choose from a very small number of straits such as the Strait of Malacca and the Strait of Sunda, which are very easily blockaded and controlled.”25 It is not just a matter of distance or power gradients; geography still matters greatly. Projecting power outward in some directions, or through some straits and potential chokepoints, may be much harder than in others.26

Closer to home, rising domestic expectations and Beijing’s need for popular legitimacy amid economic volatility, an economic slowdown, or other setbacks may motivate both geostrategic retrenchment and increased reliance on nationalism. Along virtually any strategic trajectory that China might follow, cross-strait security seems far from guaranteed. This much is clear: at a time when China under Xi Jinping is unprecedently powerful in the maritime domain, Taiwan is increasingly targeted and vulnerable.

Andrew S. Erickson is a Professor of Strategy in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the U.S. Naval War College.

The views expressed are the author’s alone. He thanks Ian Chong, Peter Dutton, Ian Easton, Isaac Kardon, Conor Kennedy, Daniel Koss, Ryan Martinson, Andrew Rhodes, and anonymous reviewers for invaluable inputs.

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

ENDNOTES

- Andrew Rhodes, “Thinking in Space: The Role of Geography in National Security Decision-Making,” Texas National Security Review 2, no. 4 (2019): 90–108, https://tnsr.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Rhodes_TNSR-Vol-2-Issue-4.pdf.

- This quote is from correspondence with the author and colleagues on September 8, 2023, and subsequent in-person discussions. Dutton elaborates: “China pursues its security through interior strategies that involve the development of rings of security around central areas of national interest. The Chinese have long felt vulnerable from the sea and their current maritime strategy seeks to reduce that vulnerability by extending a ring of maritime control around China’s periphery.” He adds that “the aim of China’s regional maritime strategy is to expand China’s interior to cover the maritime domain under an umbrella of continental control.” Peter A. Dutton, testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Committee Hearing on China’s Maritime Disputes in the East and South China Seas, January 14, 2014, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/AS/AS28/20140114/101612/HHRG-113-AS28-Wstate-DuttonP-20140114.pdf.

- Andrew S. Erickson, “Through the Lens of Distance: Understanding and Responding to China’s ‘Ripples of Capability,’” University of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, Policy Brief, no. 9, January 2012, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9t8894kv.

- From early dynastic days, China’s self-defined strategy, doctrine, and security interests have embodied its own internal politics and geography. Nearly every Chinese regime that successfully establishes a strong, unified state and achieves domestic order has sought to maximize its control or influence over a geographically grounded strategic periphery; and thereby set regime boundaries at the maximum level permitted by geophysical, economic-administrative, and military-political constraints. Accordingly, regime vicissitudes generate corresponding patterns of peripheral territorial expansion and contraction. For further discussion, see Michael D. Swaine and Ashley J. Tellis, Interpreting China’s Grand Strategy: Past, Present, and Future (Santa Monica: RAND Corporation, 2000), 9–45, https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1121.html.

- The PLA was successful in raising the cost of these activities and thereby reducing them, but they continued well into the early 1970s and were only halted by U.S. political decisions after Richard Nixon went to China.

- Andrew Rhodes, “The 1988 Blues—Admirals, Activists, and the Development of the Chinese Maritime Identity,” Naval War College Review 74, no. 2 (2021): 61–79, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol74/iss2/6.

- Liza Tobin, “Underway—Beijing’s Strategy to Build China into a Maritime Great Power,” Naval War College Review 71, no. 2 (2018), https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol71/iss2/5.

- Xu Qi, “Maritime Geostrategy and the Development of the Chinese Navy in the Early Twenty-First Century,” China Military Science,” trans. Andrew S. Erickson and Lyle J. Goldstein, Naval War College Review 59, no. 4 (2006): 46–67, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol59/iss4/5.

- Ryan D. Martinson, “The Role of the Arctic in Chinese Naval Strategy,” Jamestown Foundation, China Brief, December 20, 2019, https://jamestown.org/program/the-role-of-the-arctic-in-chinese-naval-strategy. See also Camilla T. N. Sorensen, “The Polar Regions as New Strategic Frontiers for China,” National Bureau of Asian Research, January 25, 2024, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/the-polar-regions-as-new-strategic-frontiers-for-china.

- Ryan D. Martinson, “Maritime Strategy and Naval Transformation” (paper presented at “Going Global? The People’s Navy in a Time of Strategic Transformation” conference, Newport, May 6, 2019); and Liu Lijiao and Chen Wenhua, “Gaige kaifang yilai haijun zhanlüe lilun de fa zhan ji jingyan qishi” [Theoretical Development of Naval Strategy since Reform and Opening Up and Implications for Today], China Military Science 6 (2018): 62, trans. by the China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI).

- Most notably, Xi has broken with Deng Xiaoping’s, Jiang Zemin’s, and Hu Jintao’s prioritization of the economy, diplomacy, and long-term development. He instead emphasizes near-term party power and control as well as expensive, technologically risky, state-of-the-art military megaprojects and coercion at increasing cost to China’s international image, foreign relations, societal demands, and future economic growth.

- “The Grand Canal…epitomizes how Chinese state-builders reconfigured the empire’s political geography in defiance of natural drainage systems,” explains a revealing analysis. “The history of Chinese state-building is at least in part a history of state-builders overcoming geographically predetermined patterns.” More broadly, Qing rulers’ mental map and administrative priorities across a vast empire reflect challenges and statist solutions that resonate today. See Daniel Koss, “Political Geography of Empire: Chinese Varieties of Local Government,” Journal of Asian Studies 76, no. 1 (2017): 161.

- Douglas MacArthur, “Old Soldiers Never Die” (address to Congress, Washington, D.C., April 19, 1951), available at https://www.loc.gov/resource/mcc.034/?sp=4&st=image.

- “China Sails through First Island Chain,” China Daily, August 2, 2013, http://en.people.cn/90786/8350100.html.

- Andrew Rhodes, “The Second Island Cloud: A Deeper and Broader Concept for American Presence in the Pacific Islands,” Joint Force Quarterly 95 (2019): 46–53, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-95/jfq-95_46-53_Rhodes.pdf.

- Andrew S. Erickson and Joel Wuthnow, “Barriers, Springboards and Benchmarks: China Conceptualizes the Pacific ‘Island Chains,’” China Quarterly 225 (2016): 1–22.

- Shou Xiaosong, ed., 战略学 [Science of Military Strategy] (Beijing: Military Science Press, 2013), 244–47.

- Ibid., 246.

- For further analysis, see Andrew S. Erickson, “Doctrinal Sea Change, Making Real Waves: Examining the Naval Dimension of Strategy,” in China’s Evolving Military Strategy, ed. Joe McReynolds (Washington, D.C.: Jamestown Foundation, 2016), 99–132.

- Sun Liang et al., “Woguo weilai zuozhan fangxiang tazhan fenxi yanjiu” [Analysis and Research Regarding the Future Expansion of China’s Operational Direction], Ship Electronic Engineering, May 5, 2020, 8, trans. by CMSI.

- Yuan Peng, who is the vice minister of the Ministry of State Security and was formerly president of the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, offers a terrestrial equivalent. He explains that the “great periphery” for BRI “should be a ‘concentric circle’ structure with China at the core, specifically including ‘three rings.’ The ‘inside ring’ consists of the fourteen countries contiguous to China on land; for particular geographical and historical reasons, these are irreplaceably important for China. The ‘middle ring’ consists of the maritime countries extending from the ‘inner ring,’ and also areas from the west Pacific to the Indian Ocean to the Middle East and then to parts of central Asia and Russia that are not directly contiguous on land with China. The ‘outer ring’ continues to extend out to the circle of Africa, Europe, and America, including the poles.” Yuan Peng, “Guanyu xin shiqi zhongguo da zhoubian zhanlüe de sikao” [Thoughts on China’s Great Periphery Strategy in the New Period], Contemporary International Relations 10 (2013): 31.

- Xiao Tianliang, “‘Zuozhan yun’ ba lianhe zuozhan tui xiang geng gao cengci” [“Operational Cloud” Promotes Joint Operations to a Higher Level], PLA Daily, January 5, 2016, http://military.people.com.cn/n1/2016/0105/c1011-28013286.html.

- This map is based on a map produced by No. 1206 Plant, which is an enterprise supporting China’s military that produces military and civilian maps, atlases, books, periodicals, and magazines. A physical copy was viewed by the author. Further background on the map is available at https://baike.baidu.com/item/%E5%8F%A4%E4%BB%8A%E4%B8%9D%E7%BB%B8%E4%B9%8B%E8%B7%AF%E2%80%9C%E4%B8%80%E5%B8%A6%E4%B8%80%E8%B7%AF%E2%80%9D%E5%85%A8%E6%99%AF%E5%9C%B0%E5%9B%BE/50005431.

- Beyond existing bases in Djibouti and Ream, Cambodia, the next set of prioritized PLA Navy ports could include Khalifa, Abu Dhabi; Gwadar, Pakistan; and Hambantota, Sri Lanka. For further discussion, see Isaac B. Kardon and Wendy Leutert, “Pier Competitor: China’s Power Position in Global Ports,” International Security 46, no. 4 (2022): 9–47, especially the appendix; Cristina L. Garafola et al., The People’s Liberation Army’s Search for Overseas Basing and Access: A Framework to Assess Potential Host Nations (Santa Monica: RAND Corporation, 2022), https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1496-2.html; and Clark Banach and Jacob Gunter, “How the BRI Is Shaping Global Trade and What to Expect from the Initiative in Its Second Decade,” Mercator Institute for China Studies, Global Competition Tracker, December 1, 2023, https://merics.org/en/tracker/how-bri-shaping-global-trade-and-what-expect-initiative-its-second-decade. A second set of potential PLA Navy ports includes Chittagong, Bangladesh; Bata, Equatorial Guinea; Kribi, Cameroon; Luganville, Vanuatu; Nacala, Mozambique; and Nouakchott, Mauritania. See Alexander Wooley et al., “Harboring Global Ambitions: China’s Ports Footprint and Implications for Future Overseas Naval Bases,” AidData, William & Mary, July 2023, 1–4, 35–37, https://www.aiddata.org/publications/harboring-global-ambitions.

- Li Jian, Chen Wenwen, and Jin Jing, “Yinduyang hai quan geju yu zhongguo hai quan de yinduyang tazhan” [Chinese Sea Power Expansion and the State of Sea Power in the Indian Ocean], Pacific Journal 22, no. 5 (2014): 74, trans. by CMSI.

- In light of these challenges, researchers at the PLA Navy Submarine Academy discuss how PRC submarines can play a crucial role in “expand[ing] maritime strategic space,” “protect[ing] Far Seas strategic channels,” and “protect[ing] security of Far Seas passages.” Hu Dongying, Huang Rui, and Cai Guangyou, “Tuijin qian jian bingli zouxiang yuanyang de ji dian sikao” [Several Thoughts on Advancing the Submarine Force to Distant Oceans], Ship Electronic Engineering 1 (2017): 1–3, trans. by CMS.