In the German Kaiserreich (1871–1918) there existed a complex political culture of imperialism, much of which was entangled with other aspects of German public life. The culture comprised many elements, and from them more than one imperialist ideology was constructed. This commentary focuses on four particularly important aspects of German imperialist culture.

A few caveats are required upfront. These observations about German imperialism adopt the standpoint of political culture as the concept is employed by political anthropologists. I will attempt to identify certain connected sets of attitudes, beliefs, speech forms, images, and repeated behaviors that informed the aims and actions of Germans who considered themselves to be imperialists, that gave meaning to their ideological constructions, and that filled in their maps of the world. Although political culture is not a particularly useful approach to accounting for or predicting specific events, it can facilitate understanding of the contexts in which decisions are made.

The Specter of Great Britain

Images of Britain loomed over German public life throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The affective aspects of these images were often contradictory, even in the minds of individuals: fear, desire to emulate, envy, admiration, and occasionally disdain. During the period of the Kaiserreich, images of the United States tended increasingly to become connected to those of Britain, often through the category “Anglo-Saxon.” To Germans thinking, talking, and writing about their country’s relationship to the world overseas, Britain was unavoidable. The British had apparently defined the forms though which modern Europeans engaged with the rest of the globe, and they possessed the naval and financial power to structure such engagements to their own liking. Germans often exaggerated the practical extent of British power. Those with significant knowledge of commerce usually realized that the current world economy had been created not by the British alone but through the activity of Europeans of various nationalities, no small number of whom had been Germans. What the British had done was coordinate an international effort, maintain a loose hegemony over it, and bend it to their own advantage.1

To Germans who consciously advertised themselves as “imperialists,” images of Britain were even more central. Most were aware that they were directly imitating a British political fashion, with attendant terminology, that had appeared in the 1870s and 1880s. As a form of political expression and as a way of conceptualizing political action, the “new imperialism” was largely an adaptation of a British product. Although in fact the wide array of ideological and practical elements that came quickly to be attached to imperialism in Germany arose from many sources, they were mostly constructed so as to appear to be derived from and validated by the British imperial experience. Modes of colonial governance, “native policies,” models for colonial architecture, and the foreign policy stance known as “Weltpolitik” were represented in this way. Even when it came to Eastern Europe, where imperialists made much of centuries of German movement and colonization, it was the forms of Anglo-Saxon settlement in North America and Australasia that were customarily taken as the appropriate models for future German expansion.

To imperialists, Britain was at once the aspirant model for Germany and the prime obstacle to achieving equivalent status. Anglo-Saxon success at managing migration and establishing new European societies was admired by imperialists, but the ability of these societies to absorb emigrant Germans and to “de-Germanize” them was perceived as dangerous. Although British naval power was not as great a danger as were the French and Russian armies, it certainly was a threat to German overseas aspirations. This explains the need to build a fleet that could engage the British navy and perhaps encourage British cooperation in German imperial expansion. Caught in the complexity of their obsession with the imperial Britain that they imagined, German imperialists could almost not help advocating policies that in practice worked against the accomplishment of many of their aims.

The Weight of History

Constructions of history are a fundamental part of the political cultures of modern nations. Nineteenth-century Germany was no exception. Indeed, the performance of Germans in constructing their national history served as a model for other peoples around the world. In the political culture of imperialism in the Kaiserreich, certain propositions were generally accepted. Historically, Germans were colonizers. Imperialist imaginations portrayed the spread of Germans into the Slavic East during the Middle Ages as the principal cause of the region’s economic and intellectual advancement so as to legitimate their expansionary aspirations in the present. Likewise, the fact that Germans had once ruled areas now part of the Russian empire was frequently taken as establishing a right to do so again.

Imperialists also drew on the conventional German narrative of more recent times, in which Germans had continually been taken advantage of by other countries. Although individual Germans and German firms had been significant participants in the establishment of European overseas hegemony, their participation had taken place under the protection of Spain, the Netherlands, and in later years Britain, resulting in no significant political gains for the German states. The contemporary consequences of having no overseas empire were, so it was said, potentially dangerous. Germany had become a major exporter of capital, and German firms were involved in commerce throughout the world, but typically as parts of networks of business relations centered in Britain and often dominated by British companies. German banks were active in the United States, but the principal firms on Wall Street were showing distressing tendencies to align themselves with those of the City of London.

To convinced imperialists (supported by the directors of German firms seeking various forms of state backing), this meant that Germany had to move decisively to establish a powerful political presence around the globe. German investors in the late nineteenth century were doing very well in a financial and commercial world in which Britain—and increasingly, the British-American connection—held the upper hand, but who knew when that might change? And of course it did change in 1914, with the anticipated consequence of Germany’s being cut out of international financial markets. The onset of World War I must at least to some extent be ascribed to the aggressive policies that the German imperialists had demanded as a way to prevent that very consequence.

Pride and Self-Doubt

Another significant element of the political culture of German imperialism appears at first glance to be entirely social-psychological: a pattern of connected attitudes that evinced both intense pride in the recent accomplishments of Germans and fear that Germans, as a people, would be unable to maintain the same pace in the future. Similar patterns can be found in most modern political cultures and ideologies. What is interesting in the case of German imperialism is the specific forms that the pattern took. Racial factors (in the broadest sense of the term) were heavily emphasized. General xenophobia and feelings of racial revulsion played a role, but among imperialists racism was typically embodied in more “objective” assertions. German pride in constituting one of the world’s ruling peoples was often linked to suspicion that other peoples of equivalent status (the British especially) did not sufficiently appreciate German capacities, as well as to fear that contemporary Germans would fall short of the mark. With regard to non-European peoples, the counterpoint to racial pride was also fear: in the colonies, fear that miscegenation would undermine the racial superiority on which colonial rule rested; in Asia, fear that Japan and China possessed the capacity to wrest control of the world from European hegemony.

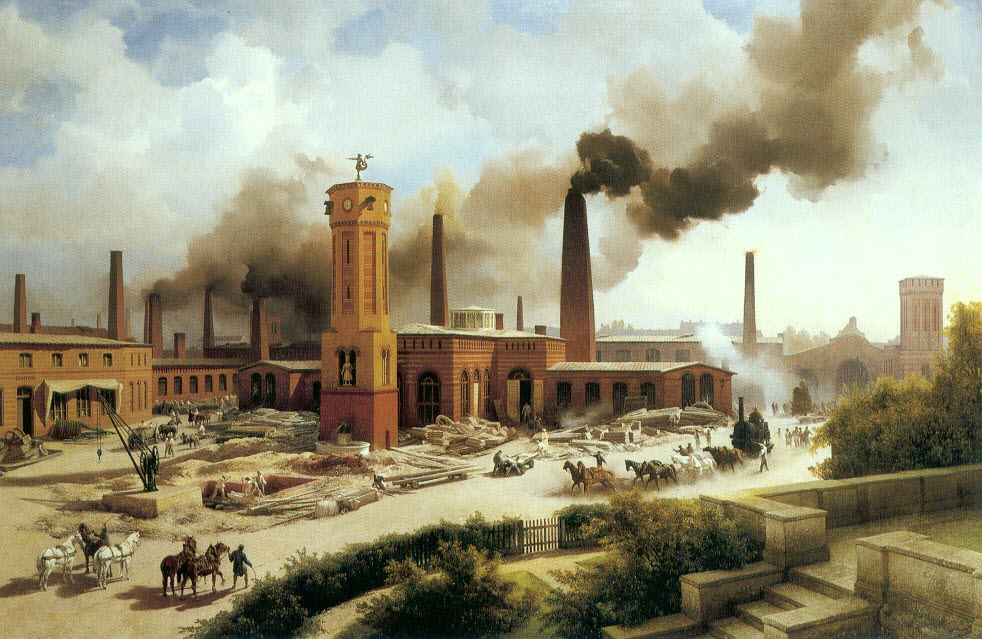

There were also domestic sources, such as the fear that a socialist working class would destroy the social order that had produced German progress in the nineteenth century or the fear that modern society and industrialization would undermine the cultural and personal virtues that made the Germans a great people. What came next was essentially the same. German imperialists argued that something must be done to prevent these fears from being realized: rally the working classes to imperial expansion, ship Germans off to settlement colonies where they can develop the personal qualities needed to prevent racial decay, ban miscegenation in the colonies, prevent China from becoming a larger, more dangerous Japan.

The Imperatives of Geopolitics

What has been said already about imperialism in the Kaiserreich can be visualized as features of a mental map. This map was metaphorical and heuristic, and also full of inconsistencies and contradictions. But imperialism had an advantage over many other varieties of German political culture in that it was easily presented on “real” maps, which imparted to it an impression of objective reality. Of course, others could use maps as well. Otto von Bismarck is said to have dismissed a map of colonial Africa, and by implication arguments made from it, by saying, “Here is France, here is Russia, and we are in the middle. That is my map of Africa.”

Representational geography was not simply a rhetorical device, however. It was part of the conceptual structure of imperialism. Latent in imperialist maps was a Hobbesian geopolitics that held that if a country did not adjust its relations with other nations to its own benefit, some other country would. German imperialists could look at a map of China and perceive the country as a promising market, but only if Germany had the power to reserve a large piece of it for itself. They could look at a map that showed Germany’s largest actual and potential trading partners (Britain, Russia, and the United States) and see markets from which they would be cut off unless Germany followed an aggressive naval policy and an expansionary colonial one.

When confronted with Bismarck’s map of a potentially encircled Germany, imperialists ran into difficulties. Fear of encirclement was an aspect of most geopolitical imaginaries in Germany, whether imperialist or not. Bismarck himself, dubious about imperialism, was briefly willing to accept limited colonial expansion in part because he thought it might set off a colonial race among the other powers that would keep them from uniting. He lived to regret it. More thoroughgoing imperialists had to convince others, and themselves, that increasing German power and territory overseas would somehow counter the implications of Bismarck’s map, or else that Germany needed to acquire a territorial “buffer” around its borders, even though trying to do so would almost undoubtedly bring the encircling states together.

Within the framework of a political culture, maps are not objective portrayals of reality. Instead, they objectify assumptions on which other elements of the culture rest and render those assumptions as unquestionable imperatives. These imperatives were extremely persuasive in the context of German imperialism, not only as instruments with which politicians and interest groups tried to convince others to do what they wanted but also as assertions in which many of the same politicians and groups believed implicitly.

Conclusion

There were several other aspects of imperialist culture in the Kaiserreich, but the four discussed above are the ones most likely to interest readers concerned with similar phenomena in other places and times. These four are an emphasis on Britain as an imperial model and threat; the use of German history as a source of motives for expansion; an attitudinal context of national, ethnic, and racial pride matched by self-doubt; and a set of geopolitical imperatives embodied in ideologically loaded cartography.

I have not attempted to discuss the sources or purposes of these aspects of imperialist culture. I have only hinted at their effects on Germany’s performance in world politics, which ranged from mildly self-defeating to utterly disastrous. Moreover, the specific circumstances under which imperialism functioned in German and European politics in the 19th century were quite different from those obtaining in the 21st century (except, perhaps, in the case of contemporary Russia). But an examination of the political culture of German imperialism may suggest useful insights into present-day political cultures.

In the Kaiserreich, the culture of imperialism did not extend to all parts of the politically active public. Like most political cultures, it was far from homogeneous. It contained numerous practical and ideological contradictions, some of which, when they affected national policy, produced undesirable results. Although many persons in positions of authority recognized this problem, they did remarkably little about it, treating the growing dangers arising from imperialism as though they were inevitable. More than a century later, we can see that they were probably mistaken. Can we see this with regard to some of the similar beliefs that arise from our own political cultures?

Woodruff D. Smith is Professor of History Emeritus at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

“Flags of a Free Empire, Showing the Emblems of British Empire throughout the World,” 1910. | Wikipedia: Public Domain

Proclamation of Wilhelm I as emperor of Germany at Versailles, France, in 1871. | Wikipedia: Public Domain

The BASF chemical factories in Ludwigshafen, Germany, 1881. | Wikipedia: Public Domain

Ironworks Borsig, Berlin, 1847. | Wikipedia: Public Domain

Map of German Reich 1871–1918. | Wikipedia: CC BY-SA 2.5