China’s strategic conception of and engagement with outer space has evolved over time depending on each major leader’s personal ambition for the country as well as the international environment they faced. Under Mao Zedong, China’s strategic interest in the space sector was for military development and technological prestige.1 During Deng Xiaoping’s reign, the country’s space interests added a dimension of economic and social development as part of a general focus on high-tech investment. Xi Jinping’s strategic vision for China’s engagement in outer space appears to be more comprehensive, with a focus on the global political prestige afforded to space powers and the influence accrued to shape international rules and norms as a result. Foundationally, Xi’s expanded focus is still rooted in emphasizing leadership in space as crucial to achieving military modernization, innovation, technological advancement, and economic and social development.

This essay argues that under Xi, China has more fully recognized the strategic importance of outer space. Xi’s China has identified space development and exploration as a key to not only transforming the country into an aerospace power but also achieving the larger “Chinese Dream” of becoming a strong, “nationally rejuvenated” nation. It first presents a historical overview of the foundations of China’s space sector, followed by a breakdown of the strategic drivers for China’s space engagement in the context of its larger national modernization effort and their future implications. The essay concludes with a summary of themes commonly associated with China’s discussion of space as a frontier of science and its role in helping achieve national technological self-reliance.

Historical Background: The Evolution of China’s Strategic Thinking about Space

Military foundations. China’s space program is founded on the country’s initial interest in supporting its ballistic missile and nuclear industry development.2 In 1956, China established the Ministry of Defense Fifth Academy—considered the birthplace of China’s space program—following Premier Zhou Enlai’s proposal to the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that the nation establish an institution dedicated to improving R&D for missiles, technology, and manufacturing.3 A year prior, U.S.-educated aerospace engineer Qian Xuesen—the “father” of China’s space program—was deported from the United States to China and, while visiting the Harbin Institute of Military Engineering, stressed that China must keep pace with foreign missile and technology development.4

Qian Xuesen played a key role in China’s “Two Bombs, One Satellite” project,5 initiated in 1958 and primarily focused on developing China’s first nuclear weapon, by supporting its space component. Overly optimistic timelines for product delivery, constant shifts in political priorities, and turmoil under Mao ultimately scaled back space-specific development goals (see Appendix 1 (PDF)). During the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, the space program was shielded under the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), in part thanks to rocket program chief designer Zhao Jiuzhang’s proposal to share resources between the satellite and ballistic missile programs.6 On April 24, 1970, China became the fifth nation to launch its own satellite. The successful launch bolstered the CCP regime at home and abroad by providing a major technological achievement to be used in domestic propaganda and demonstrating China’s ability to deliver nuclear warheads to the mid-Pacific via the Long March 1 rocket. During the Mao era, space-relevant technologies and investments were primarily meant for military use.7

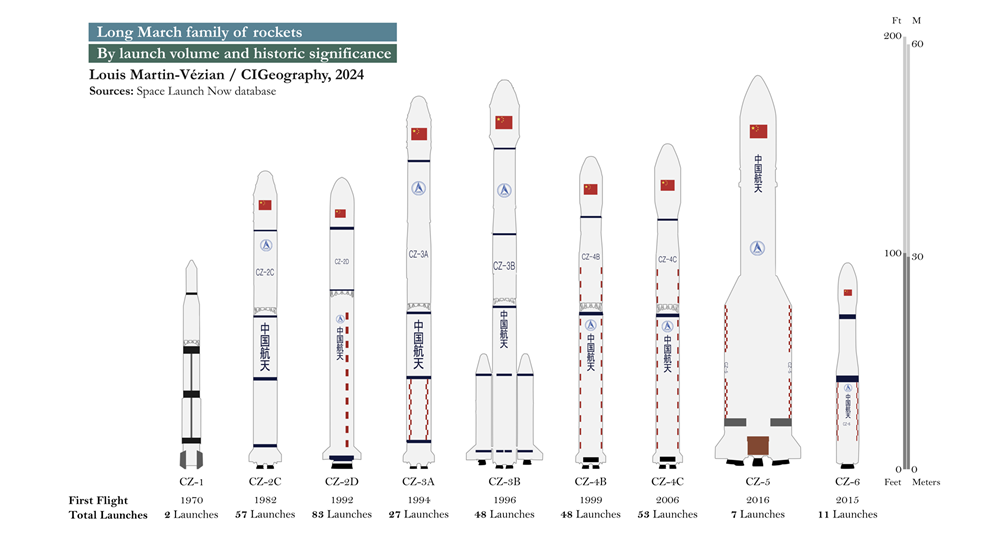

Years of first flight and numbers of launches of Long March rockets.

Economic shifts. Beginning with Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s, China’s space sector expanded its focus to support economic and social development as part of an overall effort to strengthen domestic science and technology infrastructure.8 Deng’s approval of the 863 Program in 1986 initiated China’s focus on developing domestic capabilities to produce advanced technologies across a variety of industries, including space.9 As a result, China’s space program had more dedicated resources and government support, allowing for long-term planning, and had societal and commercial impacts, such as via the introduction of satellite television throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.10

In the early 1990s, the U.S. military’s use of ground- and space-based information systems in the First Gulf War led PLA strategic thinking to conclude that the military use of space would be critical for future warfare. The PLA’s 2015 military reorganization is the latest effort that reflects the Chinese military leadership’s assessment that space is a major battlefield that the PLA needs to control in order to win wars. Current modernization efforts focus on joint force operations and have led to the consolidation of military space, cyber, and electronic warfare forces into the new PLA Strategic Support Force, while the PLA Second Artillery Corps became the Rocket Force, overseeing nuclear and ballistic missiles and other glide vehicles.11

An expanded strategic role. The early 21st century has seen China’s space program achieve a number of milestones, including its first crewed space mission in 2003 and an anti-satellite missile test in January 2007.12 Since 2019, globally recognized Chinese space program successes include being the first country to land a lunar rover on the far side of the Moon (Chang’e-4, 2019), deploying its own global navigation satellite system (GNSS) (BeiDou, 2020), becoming the third nation to successfully land and establish communication with a rover on Mars (Zhurong, 2021), and completing its own space station (Tiangong, 2022).13

Orbitual paths of BeiDou satellites.

From the late 1990s onwards, the United States began to impose restrictions on space-related technology transfers, prompted by the 1999 Cox Report, which relayed concerns about nuclear missile and weapons of mass destruction technology transfer and has been described by some U.S. political analysts as a “worst-case assessment.”14 The Cox Report was followed by the 2011 Wolf Amendment, which requires NASA and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy to receive approval from Congress before engaging with China’s civil and commercial space entities.15 During this time, China has turned the relative isolation of its space sector into a motivating factor to actively cultivate its domestic commercial space industry alongside adjacent industries of relevant interest, such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and new materials, and champion national space efforts across society.

In 2014, China’s National Development and Reform Commission released Document 60, which gave private investors and entrepreneurs the opportunity to compete with state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the space sector.16 While SOEs continue to lead China’s space programming, the opening of the commercial space sector led to provincial governments out-funding the central government in terms of R&D contracts for space products and services, likely seeking a considerable economic boost as a result in the future.17 Meanwhile, likely to cultivate societal buy-in to the its burgeoning space program, China in 2016 inaugurated its annual Space Day, held on April 24 to commemorate the launch of the country’s first satellite.18

Looking forward, China’s private spaceflight companies continue to pursue avenues for advanced yet cheaper launch technologies, with major foreign commercial launch successes like SpaceX serving as a goalpost for China-based entrepreneurs.19 Other major plans include the deployment of a national broadband satellite internet constellation in low-earth orbit,20 the expansion of applications and services that use the BeiDou satellite system as part of the Belt and Road Initiative’s Digital Silk Road, and landing a person and establishing a base on the Moon by the 2030s.21 Strategically, the completion of the BeiDou GNSS affords China freedom from having to rely on foreign GNSS (e.g., the United States’ GPS, Russia’s GLONASS, and the European Union’s Galileo). Additionally, fielding a national broadband satellite constellation builds network resilience and expands national satellite internet coverage. China appears on course to achieve its space program ambitions under Xi Jinping.

Modern international space law has not kept pace with the current global space landscape, which involves more national and commercial actors than when the foundational treaties were introduced (see Appendix 2 (PDF)).22 Additionally, while guidelines promulgated by leading space nations, such as the 2020 U.S. Artemis Accords, seek to provide a shared set of principles for responsible space activity, these frameworks are not legally binding.23 As China’s status as a global space power has risen to arguably second in the world only to the United States, its interests have grown to include shaping international space law and norms.24 The Chinese government has indicated a high interest in the formulation of international space rules, such as by increasing its engagement with the International Telecommunication Union, the UN body responsible for managing the radio-frequency spectrum and satellite orbits.25

Drivers and Implications: Space in China’s National Modernization Effort

Based on government statements and the sector’s development history, the main strategic drivers of China’s space program are innovation in science and technology, military modernization, economic and social development, and global prestige. Each of these drivers align with core CCP interests, including providing public goods and services, building a world-class modern military, framing the party in a politically competent and prestigious light, and modernizing the nation. Table 1 lists the core drivers of China’s space program and their respective key points.

Table 1: The Primary Strategic Drivers of China’s Space Program

Xi has repeatedly noted that the aerospace dream is an important part of China’s larger ambition of becoming a “strong country.”26 Becoming a strong country is fairly synonymous with achieving China’s “national rejuvenation” and would likely entail the CCP viewing China’s national development situation in a favorable light. This would include viewing military modernization efforts as a success, including the PLA’s ability to conduct joint force operations for quick and decisive battles. As a result, China would likely have greater confidence in the PLA’s ability to fight modern wars against a more technologically advanced opponent in its near abroad. This confidence would likely increase the chances of the CCP considering the use of military force in the near term as a viable option to right key historic wrongs—specifically, unification with Taiwan.

The physical nature of the space domain makes observing and accurately assigning intent or implications more challenging than in other domains, particularly given the current lack of agreed global rules and norms.27 Additionally, although not detailed here, other drivers such as bureaucratic inertia, defense establishment influence in securing budgets, or personal favoritism toward space from top decision-makers likely play a role in China’s space-related activities. Although we can infer strategic interests and ambitions from a study of China’s space program history, government statements, and activity in the space domain, verifying concrete conclusions about the country’s true intentions is a challenge.

Themes: Frontier Domains as Natural Environments That Spur Innovation

Common themes across Chinese government space-related policy documents and speeches include calls for sector self-reliance; overcoming the natural challenges that space presents through advancements in science, technology, and innovation; and the strategic role that space plays in diplomacy and international prestige.28

Self-reliance. The Chinese government’s major focus on cultivating self-reliance is a theme in a number of government space-related speeches and documents. Between 2018 and 2020, Xi Jinping called for Chinese people in the space sector to “carry on the spirit of ‘Two Bombs, One Satellite’”—a phrase that also appears in the 2021 space white paper (see Appendix 3 (PDF)).29 The phrase serves as a call to action for sector-specific professionals to overcome the inherent difficulties and hurdles of engagement with the space domain through hard work, likely regardless of whether the challenge is technological, bureaucratic, or domain-specific.

Overcoming challenging environments through technology and innovation. Chinese government policy documents, such as the 14th Five-Year Plan and releases from the Ministry of Natural Resources, have highlighted space and other physical frontier domains as important for science and technology development. Sometimes referred to as “deep space, deep sea, and deep earth,” these physical frontiers are often featured for their role in spurring innovation and domestic and global cooperation in advanced technologies due to their naturally challenging environments.30 Technologies highlighted in connection with these domains tend to focus on improving natural disaster monitoring and response; addressing energy, resource, and environmental needs; supporting Chinese business efforts; and boosting China’s global influence.31 The deployment of modern information systems, such as BeiDou, is frequently highlighted as key in supporting innovation-driven development and deepening integration between science, technology, and the economy via various services that can be provided as a result.

Diplomacy and international prestige. The Chinese government sees space as a vehicle for diplomacy via economic, scientific, and technological collaboration and has regularly voiced support for working with interested countries. As China’s space capabilities have grown, more statements have seemingly appeared highlighting the country’s growing ambition to take a leading role in the global arena of space engagement. A key example of this is the phrase “promote the construction of a community of common destiny in the field of outer space,” which frequently shows up in China’s 2021 space white paper. 32 A version of the phrase also appears in the 2011 space white paper.33 However, the full phrase appears to only prominently take shape in the 2021 edition, suggesting an expansion of China’s space ambitions following a rapid maturation in national space capabilities and globally recognized milestones in the space domain.

“A community of common destiny” is likely intentionally vague; it appears to play to the globalist narrative of exploring space in service to humanity’s overall advancement as a species and overcoming national divisions on Earth. Underlying the phrase is the recognition that great powers continue to be the dominant players in the space domain while developing space powers follow; however, the narrative allows for an image of great-power benevolence and an invitation for developing countries to follow strong spacefaring countries into the future, likely to the service and benefit of China’s space diplomacy efforts.

Conclusion

China’s strategic interests and thinking about the space domain have grown from a primarily military focus of supporting the development of a nascent ballistic missile program to current ambitions to become a global space power and leader in all avenues of the space sector, including playing a more prominent role in shaping the domain’s international rules and norms. To the CCP, space is a domain of strong powers led by great powers. Historically, strong countries have been the only ones capable of pulling together both the national and international resources necessary to challenge the boundaries of human possibility in a hostile environment. In the modern era, strong countries have used space systems to improve military communications and precision. At each step, great powers have led the way. From the party’s perspective, space represents a naturally challenging environment that humanity should seek to overcome through hard work, determination, and technological innovation. The domain lends itself neatly to the CCP’s goal to foster economic, scientific, technological, and innovative strength in order to socially develop and modernize at home, as well as assume its place as a global political leader.

Under the focused efforts of Xi Jinping, China has seen numerous space milestones, all of which are particularly impressive considering the country’s relative isolation from sustained or large-scale international space cooperation. Looking forward, given the importance space plays in China’s larger national rejuvenation efforts across defense, economic, technologic, and social development, Xi’s emphasis on the strategic importance of space will likely continue.

Khyle Eastin is a Senior Intelligence Analyst at CrowdStrike, where he focuses on China and foreign and defense affairs in Asia, and a Nonresident Fellow at the National Bureau of Asian Research.

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

Year of first flight and numbers of launches of Long March rockets. | Louis Martin-Vézian/CIGeography, 2024; Sources: Space Launch Now database.

Orbitual paths of BeiDou satellites | Louis Martin-Vézian/CIGeography, 2024. Sources: Celestrak, Test and Assessment Research Center of China Satellite Navigation Office; TLE Computation: CIGeography Ground Track Generator.

ENDNOTES

- Bleddyn E. Bowen, Original Sin: Power, Technology and War in Outer Space (New York: Oxford University Press, 2023), 89.

- Bowen, Original Sin, 88.

- Li Shu Heng, “Lǎo wǔ yuan: Zhōngguó hángtiān liùshí jiǎzǐ de qǐdiǎn” [The Old Fifth Academy: The Origin of 60 Years in Chinese Spaceflight], China Aerospace Magazine, July 29, 2016, http://zhuanti.spacechina.com/n1411844/c1412221/content.html.

- Bowen, Original Sin, 89–90; and “Qian Xuesen: The Man the U.S. Deported – Who Then Helped China into Space,” BBC, October 26, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-54695598.

- China’s “Two Bombs, One Satellite” effort focused on the development and successful testing of the country’s first nuclear bomb and hydrogen bomb and the launch of a satellite (Dongfanghong 1).

- Bowen, Original Sin, 91–93.

- Bowen, Original Sin, 93.

- Bowen, Original Sin, 94.

- Joel R. Campbell, “Becoming a Techno-Industrial Power: Chinese Science and Technology Policy,” Brookings Institution, April 29, 2013, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/becoming-a-techno-industrial-power-chinese-science-and-technology-policy; and Namrata Goswami and Peter A. Garretson, Scramble for the Skies: The Great Power Competition to Control the Resources of Outer Space (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2020), 205–6.

- Anthony Kuhn, “Company Town: Chinese Wiring the Countryside for Satellite TV: Television: Program Is the First Experimental Step in Building a Nationwide Direct-to-Home System,” Los Angeles Times, September 23, 1999, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1999-sep-23-fi-13335-story.html.

- “Lùjūn lǐngdǎo jīgòu huǒjiànjūn zhànluè zhīyuán bùduì chénglì dàhuì zài běijīng jǔháng Xíjìnpíng xiàng zhōngguó rénmín jiěfàngjūn lùjūn huǒjiànjūn zhànluè zhīyuán bùduì shòuyǔ jūnqí bìngzhì xùncí” [PLA Rocket Force and Strategic Support Force Establishment Ceremony Is Held in Beijing, Xi Jinping Grants a Military Flag and Delivers a Speech to the Strategic Support Force and Rocket Force], Xinhua, January 1, 2016, http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2016-01/01/c_1117646667.htm.

- Shirley Kan, “China’s Anti-Satellite Weapon Test,” Congressional Research Service, CRS Report for Congress, RS22652, April 23, 2007, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/RS22652.pdf.

- State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), 2021 Zhōngguó de hángtiān [China’s Aerospace Sector in 2021] (Beijing, January 2022), https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2022-01/28/content_5670920.htm.

- U.S. House of Representatives, “Report of the Select Committee on U.S. National Security and Military/Commercial Concerns with the People’s Republic of China,” January 3, 1999, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRPT-105hrpt851/pdf/GPO-CRPT-105hrpt851.pdf; Jonathan D. Pollack, “The Cox Report’s ‘Dirty Little Secret,’” Arms Control Association, April 1999, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/1999-04/cox-reports-dirty-little-secret; and Joseph Cirincione, “Cox Report and the Threat from China,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 7, 1999, https://carnegieendowment.org/1999/06/07/cox-report-and-threat-from-china-pub-131.

- U.S. Congress, “Department of Defense and Full-Year Continuing Appropriations Act, 2011,” https://www.congress.gov/112/plaws/publ10/PLAW-112publ10.htm.

- National Development and Reform Commission (PRC), “Guówùyuàn guānyú chuànxīn zhòngdiǎn lǐngyù tóuróngzī jīzhì gǔlì shèhuì tóuzī de zhǐdǎo yìjiàn” [Guiding Opinions of the State Council on Innovating Key Areas of Investment and Financing Mechanisms and Encouraging Social Investment], November 26, 2014, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2014-11/26/content_9260.htm.

- Irina Liu et al., “Evaluation of China’s Commercial Space Sector,” Institute for Defense Analyses, Science and Technology Policy Institute, September 2019, iv, https://www.ida.org/-/media/feature/publications/e/ev/evaluation-of-chinas-commercial-space-sector/d-10873.ash.

- “China Kicks Off Its Space Day, Showcases Images of Mars,” State Council (PRC), Press Release, April 24, 2023, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202304/24/content_WS64468233c6d03ffcca6ec987.html.

- Liu Yang, “Zhōngguó hángtiān jìshù zhuānjiā: 2023 yòu jiāng shì yīgè hángtiān dà nián” [Chinese Aerospace Technology Specialist: 2023 Will Be Another Big Year for Aerospace], Global Times, January 5, 2023, https://mil.huanqiu.com/article/4BAb95WTtt4; “Zhōngguó hángtiān bùbì xiànmù SpaceX” [China’s Aerospace Sector Does Not Need to Admire SpaceX], Paper, June 2, 2020, https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_7652560; and Zhou Feng, “Zhōngguó, zěnme jiù méi chūlái yīgè SpaceX?” [China, How Have You Not Produced a SpaceX Yet?],” Sina, January 22, 2022, https://finance.sina.com.cn/tech/2022-01-22/doc-ikyamrmz6830271.shtml.

- “Zhōngguó xīngwǎng’chénglì!” [China Satellite Internet Is Established!], Chengdu University of Information Technology, School of RF Microelectronics, May 7, 2021, https://rfic.cuit.edu.cn/info/2095/1173.htm; and “Wǒ guó chénggōng fāshè wèixīng hùlián jìshù shìyàn wèixīng” [China Successfully Launches Internet Test Satellite], Xinhua, July 9, 2023, http://www.news.cn/politics/2023-07/09/c_1129740518.htm.

- China National Space Administration, “Guójì yuèqiú kēyánzhàn hézuò huǒbàn zhǐnán” [International Lunar Research Station Partner Cooperation Reference], June 16, 2021, https://www.cnsa.gov.cn/n6758823/n6758839/c6812148/content.html.

- Sophie Goguichvili et al., “The Global Legal Landscape of Space: Who Writes the Rules on the Final Frontier?” Wilson Center, October 1, 2021, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/global-legal-landscape-space-who-writes-rules-final-frontier.

- NASA, “The Artemis Accords: Principles for Cooperation in the Civil Exploration and Use of the Moon, Mars, Comets, and Asteroids for Peaceful Purposes,” October 13, 2020, https://www.nasa.gov/artemis-accords.

- State Council Information Office (PRC), 2021 Zhōngguó de hángtiān.

- Véronique Glaude and Cessy Karina, “Synergies for Outer Space Sustainability: Lessons from ITU Experiences,” International Telecommunication Union, October 27, 2022, https://www.itu.int/hub/2022/10/space-sustainability-synergies.

- “Fēitiān yuánmèng | Wěidà shìyè dōu shìyǔ mèngxiǎng Xíjìnpíng zhèyàng yǐnlǐng hángtiān qiáng guó mèng” [Flying to Realize Our Dreams | Greatness Begins with Dreams: Xi Jinping on Leading the Dream of a Strong Aerospace Country], People’s Daily, October 31, 2022, http://cpc.people.com.cn/n1/2022/1031/c164113-32555442.html.

- Bowen, Original Sin, 170–71.

- The 2000, 2006, 2011, and 2021 space white papers are available at the China National Space Administration website: https://www.cnsa.gov.cn/n6758824/n6758845/index.html.

- “Fēitiān yuánmèng”; and State Council Information Office (PRC), 2021 Zhōngguó de hángtiān.

- Zhao Jingyan, “Chuàngxīn kējì, xiàng shēn kōng shēn hǎi shēn dì tǐngjìn” [Innovative Technologies Support Advances in Deep Space, Deep Sea, and Deep Earth], China Mining Industry News, October 8, 2016, https://www.mnr.gov.cn/dt/hy/201610/t20161008_2333031.html; and Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, Zhōnghuá rénmín gònghéguó guómín jīngjì hé shèhuì fāzhǎn dì shísì gè wǔnián guīhuá hé 2035 nián yuǎnjǐng mùbiāo gāngyào [The People’s Republic of China 14th Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and Long-Range Objectives for 2035], March 13, 2021, https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-03/13/content_5592681.htm. An English translation of the text is available at https://cset.georgetown.edu/publication/china-14th-five-year-plan.

- Zhao, “Chuàngxīn kējì, xiàng shēn kōng shēn hǎi shēn dì tǐngjìn.”

- State Council Information Office (PRC), 2021 Zhōngguó de hángtiān.

- State Council Information Office (PRC), 2011 Zhōngguó de hángtiān [China’s Aerospace Sector in 2011] (Beijing, December 2011), https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2011-12/29/content_2618562.htm.