This is chapter 1 of the report “Mapping China’s Strategic Space.” To read the full report, download the PDF.

Before mapping what constitutes the strategic space of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), we must begin with defining what the concept entails. Broadly speaking, it can be described as the imagined space beyond China’s national borders that its leaders consider as vital to the pursuit of national political, economic, and security objectives and to the eventual achievement of China’s rise. Driven by both defensive and offensive motives, Beijing’s interest in seeking additional strategic space may be interpreted as a form of 21st-century imperial expansion. Although the “strategic space” terminology was not officially endorsed until 2013, detailed discussions of “strategic frontiers” began to emerge in Chinese military circles in the late 1980s. Well before the appearance of such specific language, however, Mao Zedong had already thought about securing and expanding China’s strategic space, as his involvement in the Korean War, his negotiations with Joseph Stalin over Mongolia and the Soviet border, his Theory of the Three Worlds, and the early 1970s clarification of claims to the South China Sea can attest. As will be further developed in the subsequent chapters, the evolution of China’s strategic thinking about the nexus between geography, space, and power is a gradual process and the result of both domestic politics and changes in China’s international security environment. For now, this chapter will focus on explaining what “strategic space” means.

Two Chinese documents provide detailed descriptions of “strategic space.” The first is a 1987 newspaper article signed by a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) senior officer who would later become the deputy director of the PLA General Staff Department. The second is a chapter in the 2013 edition of the Science of Military Strategy, an essential authoritative source that “reveals how some of the PLA’s top strategists assess China’s security environment, how military force should be used to secure China’s interests, and what kinds of military capabilities the PLA should develop in the future.”1

Origin Story

The origin of the strategic space concept can be traced back to Chinese military circles at a time when the PLA was undergoing significant doctrinal changes. During the three decades of Mao’s rule, his military doctrine had been based on his belief that, in case of an invasion, China’s geographic landmass would provide the strategic depth necessary to absorb, disperse, and defeat the enemy’s attack. His wary eye was fixated on China’s giant northern and western neighbor, the Soviet Union, the former revolutionary brother in arms with whom Mao had parted in the early 1960s. In a nutshell, his general command to his troops was to “lure the enemy in deep and actively defend.” In March 1980, Deng Xiaoping and the marshals who sat in the Central Military Commission (CMC) discarded the first half of Mao’s command and enjoined the military to focus instead on frontier defense and “active defense.” 2 The leadership’s engagement in a thorough reassessment of China’s threat environment culminated in the 1985 CMC meeting’s endorsement of Deng’s decision to shift away from preparing for total war against a massive Soviet attack.

Instead, the PLA was to get ready to fight local wars,3 i.e., “conflicts of relatively low intensity and short duration [that] could break out virtually anywhere on China’s periphery.” 4 This fundamental doctrinal shift henceforth flipped the PLA’s mental conceptualization of the strategic space it would have to operate in: from a focus on the threat of a massive-scale invasion that would mainly be coming from China’s northern and northwestern continental borders and would be faced by “luring” enemy fighters deep into the Chinese territorial landmass to a focus on conflicts possibly occurring at multiple locations along all of China’s “strategic frontiers” (zhanlüe bianjiang), which would require PLA forward deployments, including outside the national territory.

In the context of these doctrinal shifts, M. Taylor Fravel understands strategic frontiers in strictly military terms as “forward areas”—a comprehensive system of border defense including a unified land, sea, and air defense.5 Michael Swaine offers a more intricate description: “The Chinese principle of ‘strategic frontier’ is intended to encompass the full range of competitive areas or boundaries implied by the notion of comprehensive national strength, including land, maritime, and outer space frontiers, as well as more abstract strategic realms related to China’s economic and technological development.” 6 Former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe gave his own interpretation of the meaning of this concept in a 2010 speech at the Hudson Institute:

- Since the 1980s, China’s military strategy has rested on the concept of a “strategic frontier.” In a nutshell, this very dangerous idea posits that borders and exclusive economic zones are determined by national power, and that as long as China’s economy continues to grow, its sphere of influence will continue to expand. Some might associate this with the German concept of “lebensraum.”7

One of the most detailed and early explanations of the strategic frontier concept can be found in a 1987 PLA Daily article signed by Senior Colonel Xu Guangyu.8 Several international experts on the PLA have acknowledged it in their writings.9 Abe’s speechwriters must have studied it too, as will become apparent in the following description. Xu’s original text is not accessible anymore, but, fortunately, there remains a 1988 English version translated by the Foreign Broadcast Information Service.10 The article is worth unpacking as it gives precious indications about the strategic elites’ early mental map of China’s present and future strategic space. Xu writes from his perspective as a military strategist pondering the implications for the Chinese armed forces of the doctrinal revolution recently introduced by Deng Xiaoping and the CMC. His analysis rests on the fundamental question of the adequation between national defense forces requirements and national strategic goals “expressed…primarily in the different pursuit of geographic borders and strategic boundaries.” 11

Whereas geographic borders comprise “territorial land, territorial waters, and corresponding territorial air” (in other words, the three dimensions of national territory over which the government exerts sovereign rule), Xu notes that strategic frontiers are not as well defined. Yet, they “determine a country’s and a people’s living space” and are related to “a country’s interests that [its] military forces are actually able to control.” Even for a vast country like China, there are limits to what the land can provide, but progress in science and technology will enable humankind to “greatly expand [its] conquest of natural space” and “obtain all sorts of riches” it needs for its existence. For more narrowly focused military reasons, pushing the battlefield “from the geographic border to the strategic boundary” is also necessary to obtain an “early warning space and a strategic depth that are vastly larger than formerly” and will enable “earliest discovery and interception of enemy intrusions.” While geographic borders are internationally recognized and “relatively stable and defined,” strategic frontiers may “extend and retract” as comprehensive national power increases or decreases. Although they are defined by “the ability of military power to extend effective control” over them, they are in reality the “embodiment” of a country’s total “real power”—national economy, science and technology, politics, society, national defense, and foreign relations—that backs up national power. Indeed, “only countries that are strong and prosperous in a total sense can possess the power to push their strategic boundaries beyond their geographic borders.” Both “complement each other”: power enables “effective and stable” expansion, while expansion strengthens and supports power. Finally, strategic frontiers are contested spaces in which various powers compete to develop and expand: a “visible” space comprising “large tracts of continental shelf and the high seas, polar regions, and outer space,” as well as an “invisible” space of “power spheres and ideology.”

Xu’s description makes it clear that he does not understand strategic frontiers only as narrow buffer zones protecting the approaches of a country’s national territory, nor as a mere equivalent to the strategic depth usually coveted by military planners. Referring to the enduring existence of strategic frontiers throughout history, he chooses two telling examples: Genghis Khan’s continental empire, which Xu coyly describes as “strategic boundaries on land that were historically unprecedented in their vastness,” and the British empire, whose gunboats opened “strategic ocean frontiers” and enabled its “global ability to control the seas.” Could “strategic frontiers” actually be a euphemism for imperial expansion? To assuage the reader’s possible concerns about his implicit intent, Xu makes an agile distinction between, on the one hand, “hegemonist countries” with a global appetite and expansionist countries that seek “regional aggressionist” strategic frontiers and, on the other hand, “peace-loving countries” that only seek “legitimate” strategic frontiers. Unsurprisingly, China is described in the next sentence as a “peace-loving socialist country whose strategic goals are extremely clear cut”: peace and development. Xu’s implacable demonstration ensues. A peaceful and stable external environment is indispensable to achieve the double national objectives of quadrupling the gross national output value by the end of the 20th century and of China taking off during the 21st century to ensure “entering the ranks” of leading world powers by 2049. Achieving these national objectives and safeguarding its legitimate interests therefore necessitates that China “possesses” and “maintains” a multidimensional enlarged strategic space: land, sea, air, deep sea, and outer space strategic frontiers; “security space, living space, scientific and technical development space”; and “space for economic activities.” Winning the “required space for security and development is completely synonymous with the strategic policy of active defense that China pursues,” Xu asserts. This is “neither expansion of geographic borders nor expansionist or hegemonic aggressive expansion of strategic boundaries.” Presumably this is something that the reader will find reassuring.

Official Debut

The 2013 edition of the Science of Military Strategy displays many similarities with Xu Guangyu’s ideas, albeit this time using the term “strategic space” (zhanlüe kongjian) rather than “strategic frontiers.” The concept is explicitly defined as follows:

-

Strategic space is the area necessary for a nation or a country to resist against external interference and aggression, and maintain its own survival and development. Its outer edge depends not only on the national interests’ scope of expansion, but also on the distance within which military capabilities can be projected.… The national strategic space is based on the country’s territorial land, sea, airspace, and other areas under sovereign jurisdiction, and can appropriately extend and radiate according to the needs of maintaining its security and development. Strategic space expands along with the development of human economic, scientific and technological, and warfare activities, donning different features and characteristics depending on time periods.12

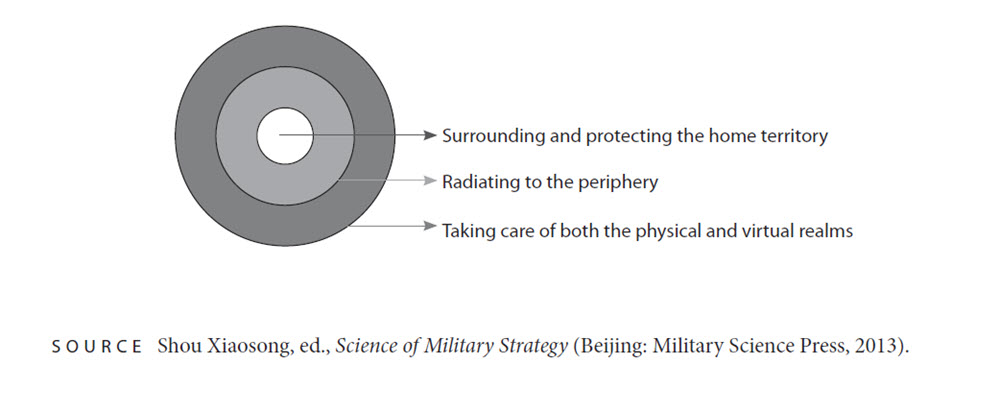

Similarly to Xu, authors of the 2013 Science of Military Strategy acknowledge that strategic space is multidimensional. Whereas Xu’s article identified three dimensions (land-sea, space, and ocean depths), the Science of Military Strategy distinguishes five of them (land, sea, air, outer space, and cyberspace) that appeared at different points in history as a result of technological advances. In the “agricultural age,” strategic space was essentially a flat, land-based surface. With progress in sea and air navigation technologies during the “industrial age,” it became a three-dimensional space. In the 1950s, outer space was added as a fourth, “high frontier” dimension. Finally, the introduction of information network technologies in the 1960s created a fifth, intangible dimension in which human society, production, and warfare now also operate.13 The traditional conception of strategic space as a flat land surface is therefore obsolete and needs to give way to a “new strategic space view,” which strives to “externally push the strategic forward edge from the home territory to the peripheral, from land to sea, from air to space, and from tangible spaces to intangible spaces, to expand the strategic depth and gradually form into a new three-dimensional strategic space: of surrounding and protecting the home territory, radiating to the periphery, and taking care of both the physical and virtual realms” (see Figure 1).14

FIGURE 1 Three-dimensional strategic space

Like Xu, the 2013 Science of Military Strategy recognizes the mutually reinforcing interaction between comprehensive national power and the extent of a country’s strategic space: “Strong comprehensive national power provides a robust support to the expansion of strategic space, while the expansion of strategic space also provides an important condition for the strengthening and promotion of comprehensive national power.” 15 Both documents have also in common their acknowledgment of the inherently contested nature of strategic space. Not only is it the case that one country’s “natural extension” will “inevitably” bump against “adjacent regions under sovereign jurisdiction,” 16 but global commons (space, cybernetworks, deep sea, and polar regions) have become “hot spots for strategic struggles” because “some developed countries take advantage of their own superiority” to create “obstacles for latecomers.” 17

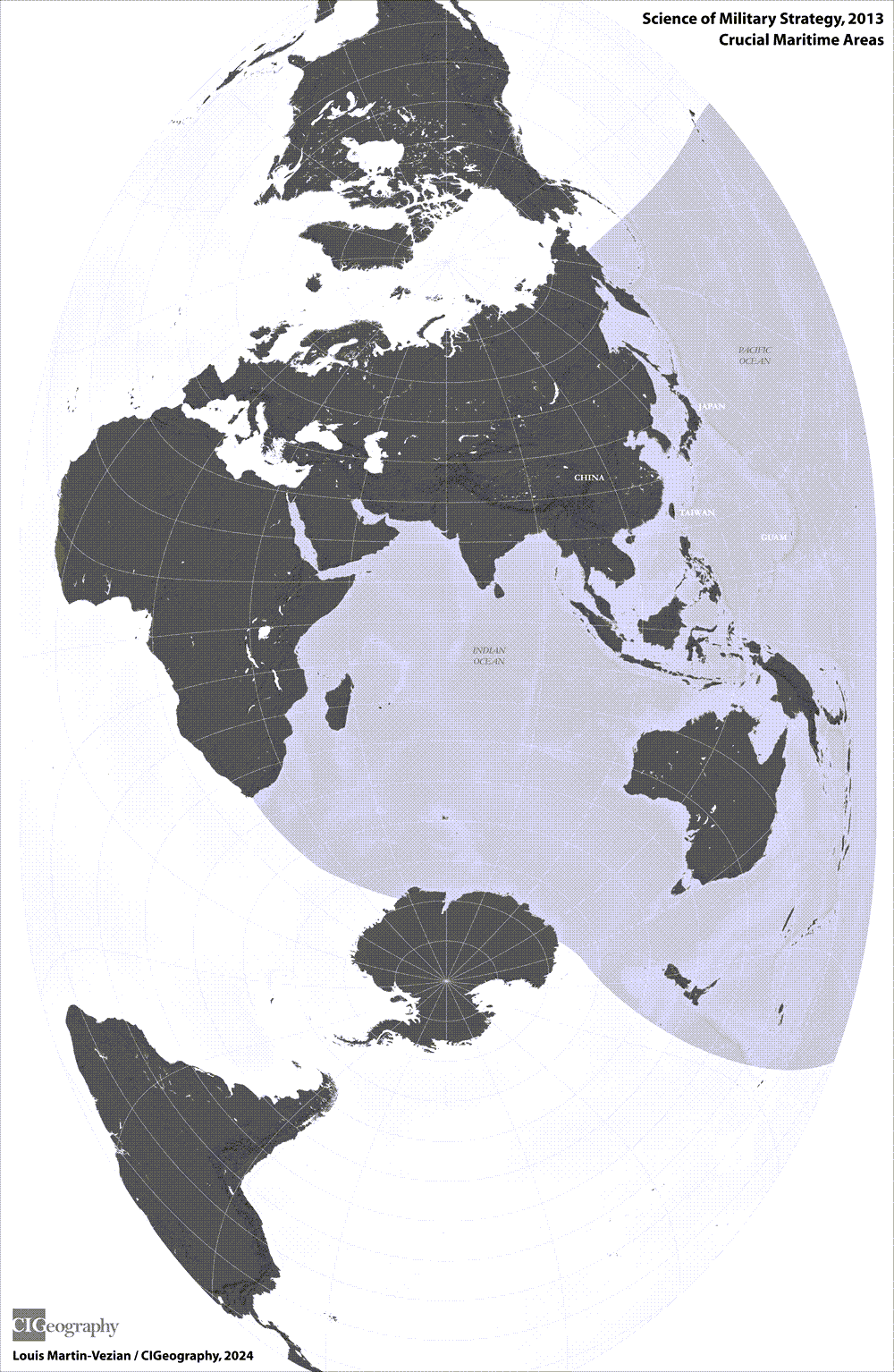

Finally, although the 2013 Science of Military Strategy does not go as far as Xu in describing strategic space as the equivalent of an imperial realm, it resonates with the senior colonel’s depiction of China’s defensive and peace-loving expansionism. The document recommends that China produce an overall plan ensuring a smooth future expansion process, stipulating, in particular, that the country “walk[ed] the road of expansion possessing the characteristics of the times and Chinese characteristics,” while maintaining a “peaceful development path” and a “military strategy defensive in nature.” 18 It thus advocates for China to “moderately expand” its strategic space.19 To that effect, China should “gradually push forward” in space and cyberspace (the “pivot”) as well as in the maritime area (the “focus”).20 In an initial effort to delineate the extent of China’s strategic mental map, the document describes this maritime area as including “the Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, as well as the littoral regions of neighboring Asia, Africa, Oceania, North America, South America, Antarctica and others,” altogether covering over 50% of the globe. This area is “crucial in influencing our nation’s future strategic development and security. It is also the intermediate zone for our access to the Atlantic Ocean region, the Mediterranean Sea region, and the Arctic Ocean region” (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 China’s maritime strategic space according to the 2013 Science of Military Strategy

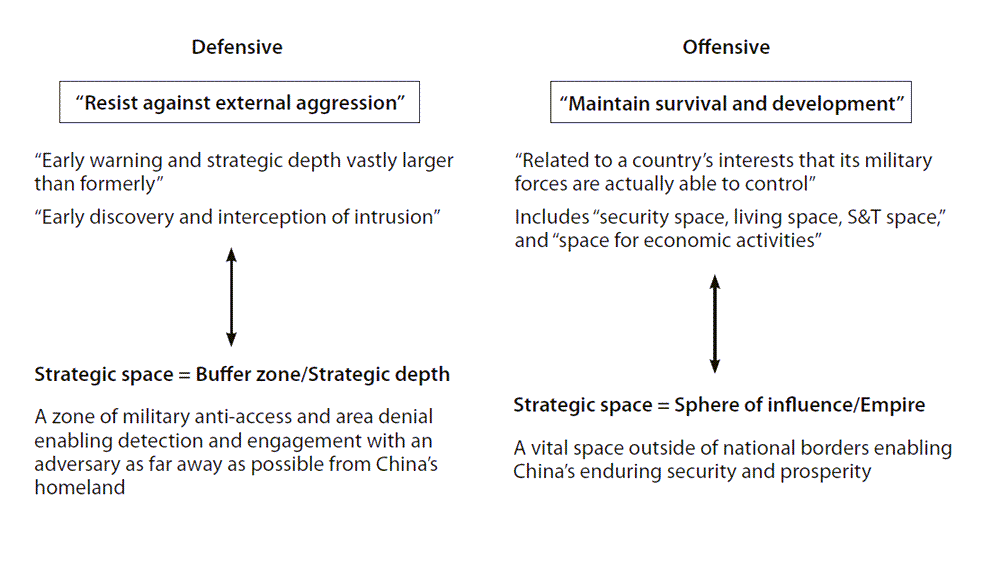

It is not totally surprising that discussions of expansion should emerge from military circles. After all, their mission is to safeguard and defend their country’s national interests. If these interests were to expand around the globe, then the projection range of the PLA would eventually need to grow accordingly. Therefore, military planners need to anticipate the scope, size, and direction of their nation’s future strategic space. Only then can they start building a force that is able to “protect China’s legitimate rights and interests,” “operate on a battlefield removed from China,” move rapidly over great distances, and fight in any of the future battlefield’s multiple dimensions.21 However, as discussed above, the strategic space concept not only covers future military areas of responsibility. It introduces the idea of outward expansion as indispensable to the enduring survival of the country, and such expansion is not narrowly confined to territorial conquest. To that effect, military expert Jacqueline Deal believes that strategic space will be used by the PLA to “make it safe for the PRC to coerce regional powers and, over time, to spread the [Chinese Communist Party’s] own rules and norms.” 22 As the 2013 Science of Military Strategy notes, strategic space relates to the “future destiny of the nation” in the process of its rise.23 Reduced to a simple equation, strategic space equals territory under national jurisdiction plus any space beyond that may be vital to the pursuit of national economic and security objectives and the enduring survival of the Chinese state. Its dual nature is summarized in Figure 3. The following chapters will unpack the perceived constraints imposed on China’s strategic space and the promises its expansion offers, as seen by Chinese strategic thinkers since the end of the Cold War.

Figure 3 The dual nature of strategic space

Nadège Rolland is Distinguished Fellow for China Studies at the National Bureau of Asian Research. Her NBR publications include China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative (2017), “China’s Vision for a New World Order” (2020), and “A New Great Game? Situating Africa in China’s Strategic Thinking” (2021).

Read the chapters online:

Introduction: Mapping China’s Strategic Space

Chapter 2: The Return of Geopolitics

Chapter 3: “Positioning” China: Power and Identity

Chapter 4: The Logic and Grammar of Expansion

Chapter 5: Conclusion: A New Map?

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

ENDNOTES

Read the chapters online:

Introduction: Mapping China’s Strategic Space

Chapter 2: The Return of Geopolitics

Chapter 3: “Positioning” China: Power and Identity

Chapter 4: The Logic and Grammar of Expansion

Chapter 5: Conclusion: A New Map?

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.