Many scholars characterize the first three decades of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule, or what is commonly called Mao’s China, as part of the Cold War. When it comes to China, however, I find this characterization misleading. It is my view that there never was a Cold War China, and this condition deeply shaped the CCP’s strategic space from the 1940s to the 1970s.1

To American ears, the claim that Cold War China did not exist might sound ridiculous. Did not the United States wage a Cold War against China to defend freedom, markets, and democracy against international socialism? Yes, it did. But that is an American viewpoint. Across the Pacific, the CCP leadership instilled in the Chinese people a drastically different understanding of geopolitics. The term “cold war” (leng zhan) had no place in Chinese discourse during Mao Zedong’s tenure in power, appearing in the mass media only a few times. This is why I maintain that the Cold War was not a salient concept in the CCP’s mental map of China’s strategic space during the Mao era, which this commentary will survey.

War and Revolution in the Mao Era

The most important concepts undergirding the CCP’s strategic mental map under Mao were war and revolution. Waging revolution against foreign imperialism to build a new socialist China had played a driving role in the CCP’s rise to power, and after seizing control of the state apparatus, the party took its central task to be militantly continuing the revolution. The CCP’s commitment to defending revolution was also why Chinese leaders recognized the term “cold war” to be a misnomer for global affairs. In Mao’s China, geopolitics could be cold for a bit but not forever, since socialist revolution was an affair of fiery passions against capitalism and imperialism.2 As Mao memorably said, “Revolution is not a dinner party.”3

The CCP’s revolutionary outlook on world affairs bolstered its conviction that the U.S.-led capitalist bloc sought to employ its geopolitical ascendancy to constrain China’s strategic space on the international stage, if not completely wipe the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and other socialist states off the map. Faced with this perilous geostrategic situation, the CCP strived to expand its influence abroad. To push back against the U.S. empire, the CCP famously leaned to one side and signed a strategic alliance treaty with Moscow in 1950. From this strategic partnership, Beijing obtained not only military and economic training and equipment but also help in establishing central agencies to oversee national development and spread Chinese influence worldwide.4

The CCP’s decision in 1950 to participate in the Korean War partially resulted from Beijing’s ambition to export China’s revolution. It was Joseph Stalin, though, that bestowed the CCP with the authority to promote revolution in Asia and granted China final say on Kim Il-sung’s plan to invade South Korea. Stalin hoped to thereby avoid fighting the United States directly, while drawing its attention away from Europe. His gambit worked, and Beijing backed Pyongyang to consolidate CCP control at home, buttress China’s standing in the global struggle against imperialism, and keep a security buffer between the U.S. military and China’s northeastern industrial heartland.5 The Korean War, however, also restricted China’s strategic space, as Washington instituted an international embargo and encircled China with security agreements and military bases from South Korea to Southeast Asia.6

Concerned about the outbreak of another war in China’s vicinity, the CCP treated development as a matter of national security, reducing consumption to channel more resources into expanding China’s heavy industrial defenses and locating some industrial facilities in the interior, far from potential front-lines.7 The Chinese government also made military-like discipline and martial language pervade everyday life, and state media regularly reminded the public to prioritize safeguarding the revolution against foreign and domestic dangers.8

For Beijing, one manifestation of U.S. hostility was granting China’s seat in the United Nations to Chiang Kai-shek’s regime in Taiwan.9 The United States’ marginalization of the PRC, however, only reinforced the CCP’s sense of the Chinese revolution’s centrality in world history, which Mao had already declared in 1947 to be at the fulcrum of two major global conflicts. The first conflict centered on the U.S. government’s drive to rally capitalist countries around containing Communism. The second conflict was Soviet-U.S. competition in what Mao called the “intermediate zone”—that is, Africa, Latin America, and Asia.10

Mao maintained that China occupied a unique position in both conflicts. For China not only supported the Soviet Union’s drive to build a socialist sphere of influence that rivaled, and eventually surpassed, the U.S.-led capitalist bloc. The CCP’s experience of fighting against imperialism and engaging in rural revolution was also more akin than the Soviet Union’s experience to the political and economic conditions of countries in the developing world. In taking this geopolitical stance, Mao reaffirmed China’s prominence in global affairs. Washington could hem in socialist China and threaten its security, but Mao and his colleagues were determined to not be contained. Their aspiration was for China’s revolution to act as a strategic template for national liberation movements and for underdeveloped countries to overcome present-day inequities and form a more egalitarian and industrialized postcolonial world.11

From War to Diplomacy

After the Korean War ended in 1953, Beijing shifted its principal tactic for enlarging China’s strategic space from waging war to engaging in diplomacy. At the center of this new approach were the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, announced in 1954. This policy called for the mutual respect of territorial integrity and noninterference in other countries’ internal affairs. Zhou Enlai drummed up support for this platform on a tour of Asia as well as at the Bandung Conference in Indonesia, where he and Indian president Jawaharlal Nehru endorsed third world countries not aligning with either the Soviet Union or the United States. Through this diplomatic offensive, Beijing challenged U.S. efforts to isolate China by establishing third world contacts and preventing certain Southeast Asian countries, some of which the CCP furnished with aid, from leaning toward Washington.12

In the late 1950s, Mao began to delink China’s strategic space from the Soviet Union’s. Wanting to reinforce his own personality cult, he disagreed with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s criticism of Stalin. Mao also saw Khruschev’s support for peaceful coexistence with the capitalist bloc as tantamount to abandoning the global fight against imperialism.13 Seeking to chart out an independent Chinese socialist path, Mao launched the Great Leap Forward in 1958 to accelerate the PRC’s transformation into an industrial powerhouse, using the second Taiwan Strait crisis to stoke nationalist fervor.14 When the campaign caused a massive famine, Beijing publicly expressed its discontent with Soviet policies for the first time, likely to divert attention from the domestic disaster.15

After the Great Leap Forward, Mao continued to exploit international strains to shore up his influence at home, mobilizing nationalist sentiment for a war with India in 1962.16 In so doing, Mao rang the death knell on Chinese participation in the Non-Aligned Movement and proceeded to cast himself as global socialism’s leader, claiming that the Soviet Union had turned into a revisionist regime where bureaucratic and technical elites prioritized their privileges over waging revolution.17 Following Mao’s orders, Zhou Enlai sought to persuade countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America to side with Beijing in the Sino-Soviet dispute and take the Chinese revolution as a model of national liberation.18

In parallel, Defense Minister Lin Biao worked with CCP colleagues to boost Maoism’s political prestige by distilling Mao’s ideas in the Little Red Book and printing over a billion copies distributed to Chinese and foreign audiences. In 1965, Lin asserted that Mao’s thought on the people’s war was “a spiritual atom bomb” that third world countries could deploy to “encircle” the first and second world and establish a new global order in which U.S. and Soviet domination no longer defined international relations.19 The CCP also invited foreign leaders and political activists to see the Chinese revolution’s accomplishments, and it offered some foreigners training in guerilla warfare, agitprop, and rural revolution. To further bolster Maoism’s global reach, the party funneled aid to third world national liberation movements and socialist insurgents, despite China’s limited resources.20

From Revolution to Reform

With these diplomatic maneuvers, the CCP increased China’s ties with radical groups abroad. Many third world governments, however, objected to Chinese support for revolutionaries in their midst and were more interested in the scale of Moscow’s or Beijing’s developmental assistance than the politics of the Sino-Soviet split.21 The CCP’s push to expand its global strategic space in the 1960s also alarmed many in Washington, who thought that if one national domino toppled into socialist hands, Beijing would only become more determined to knock more countries over into its sphere of influence.22 To contain Communist expansion, the United States enlarged its military footprint in Southeast Asia, a strategic action that the CCP mirrored by supplying China’s most extensive military and economic support to regional revolutionary groups.23

Beijing became especially worried about U.S. military activities in countries south of China after the Tonkin Gulf incident in August 1964, when Washington bombarded North Vietnam. With the flames of war growing higher on China’s doorstep, CCP leaders endorsed Mao’s suggestion that China prepare for a foreign invasion by dividing China into three war zones: a first front in the northeast and on the coast, a second front behind coastal provinces and in the far west, and a third front in central China. To the final zone, the CCP allocated around 40% of the national capital construction budget between 1964 and 1980 to build a massive military industrial complex to which the party could retreat if international adversaries occupied or damaged China’s industrial core along the coast and in the Northeast.24

Inspiration for the third front came from four sources. The first was Mao’s view that Chiang Kai-shek and Stalin made inadequate industrial preparations prior to World War II. Second, the CCP’s base areas from the 1930s and 1940s informed the government’s decision to hide and disperse projects in mountains and caves. Third, the CCP’s top brass had seen the destruction that American planes had caused during the Korean War and recognized the strategic value of seeking safety underground. Fourth, like other Cold War leaders, Mao and his colleagues considered anything visible to be militarily vulnerable, particularly given the PRC’s miniscule navy and air force and inability to launch a nuclear strike on Moscow until 1971 and on Washington until 1981.25

While the third front’s existence was kept secret until 1978, the CCP constantly warned the public that China’s security was in jeopardy. The government framed every citizen’s vigilance and hard work as vital to strengthening the nation’s economy and military readiness. The United States or the Soviet Union might invade at any moment, and so China’s citizenry had to give its all to prepping the nation for war.26 Mao and his supporters also continued to proclaim the Chinese revolution’s global significance during the Cultural Revolution, begun by Mao in 1966. Beijing called on people everywhere to stand up against American imperialism and the Soviet Union, which putatively sought to restore capitalism in China and end the socialist revolutionary project worldwide.27 To enhance the Chinese revolution’s global clout, the CCP continued to invite third world radicals and members of the European and American left to conduct tours and training in China, providing some with military and economic assistance. Most notably, it provided North Vietnam with an estimated $20 billion in aid and 430,000 Chinese troops in the late 1960s and early 1970s.28

While the CCP augmented China’s influence with radical groups abroad, the Cultural Revolution wreaked havoc on the third front in 1967 and 1968 as the CCP’s concerns about foreign penetration precipitated domestic attacks on people suspected of sympathizing with China’s international rivals.29 The party center resurrected the third front in 1969, when Beijing became worried that Sino-Soviet border skirmishes might prompt Moscow to launch a full-scale invasion.30 Preparing for war remained the party’s top economic priority until the United States lifted its trade embargo in 1971. President Richard Nixon visited China the following year, and Washington began to withdraw from Vietnam.

In the wake of this geostrategic pivot, the CCP leadership came to no longer view war with the United States or the Soviet Union as a historical inevitability. With the flames of war no longer looming ominously on the horizon, Beijing wound down the third front, cut defense spending, invested more in raising living standards, and slowly opened China’s doors to foreign trade. In this new security environment, Deng Xiaoping made “peace and development” the guiding principle of Chinese foreign policy. Chinese strategic thinking continues to echo this momentous decision, even as Beijing’s concerns about a new war with the United States, cold or hot, intensify every day.31

Covell Meyskens is an Associate Professor in the Department of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School and author of Mao’s Third Front: Militarization of Cold War China (2020).

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

The Chinese people will never forget the blood debt of American imperialism, circa 1951. | PC-195a-s-004 (chineseposters.net, Private collection)

The Sino-Soviet Alliance for Friendship and Mutual Assistance promotes enduring world peace, circa 1950. | PC-1950-s-002 (chineseposters.net, Private collection)

Together we oppose aggressive warfare and defend the peace in the Far East and the world! 1952, January. | BG E15/860 (chineseposters.net, Landsberger collection)

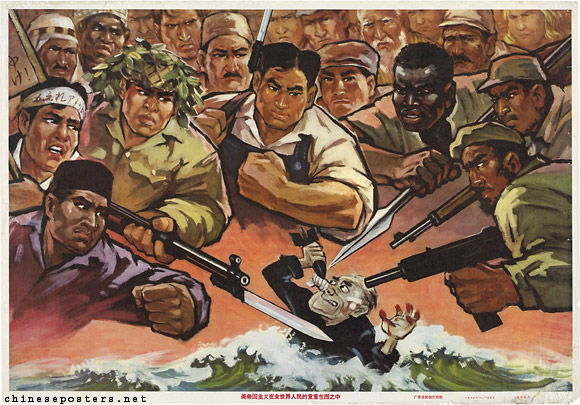

American imperialism is encircled ring upon ring by the people of the world, 1965. | PC-1965-001 (chineseposters.net, Private collection)

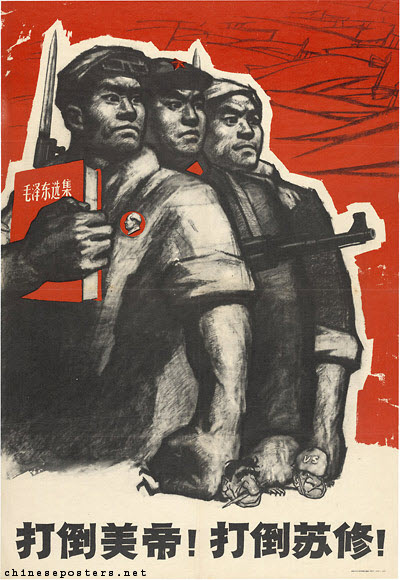

Down with American imperialism! Down with Soviet revisionism! 1969, February. | PC-1969-003 (chineseposters.net, Private collection)

ENDNOTES

- Covell Meyskens, Mao’s Third Front: The Militarization of Cold War China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 20–21.

- Chen Jian, “China’s Changing Policies toward the Third World and the End of the Global Cold War,” in The End of the Cold War and the Third World: New Perspectives on Regional Conflict, ed. Artemy Kalinovsky and Sergey Radchenko (New York: Routledge 2011), 102–4.

- Mao Zedong, “Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan,” March 1927, available at https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-1/mswv1_2.htm.

- Thomas Bernstein and Hua-Yu Li, eds., China Learns from the Soviet Union, 1949–Present (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2010); and Hua-yu Li, Mao and the Economic Stalinization of China, 1948–1953 (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2006).

- John Garver, China’s Quest: The History of the Foreign Relations of the People’s Republic (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 61–65.

- Bruce Cumings, “The Origins and Development of the Northeast Asian Political Economy,” International Organization 38, no. 1 (1984): 19–20.

- Nicholas Lardy, Economic Growth and Distribution in China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978), 40, 70–72, 88, 187–88.

- Judith Shapiro, Mao’s War against Nature: Politics and the Environment in Revolutionary China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 70–75; and Lardy, Economic Growth and Distribution in China, 1–3.

- Garver, China’s Quest, 304.

- Chen Jian, China’s Road to the Korean War: The Making of the Sino-American Confrontation (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 18–21.

- Chen, “China’s Changing Policies,” 102–4; and Jeremy Friedman, Shadow Cold War: The Sino-Soviet Competition for the Third World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 39–40.

- Garver, China’s Quest, 105–12.

- Garver, China’s Quest, 114–15, 153–56.

- Garver, China’s Quest, 142–45.

- Felix Wemheuer, A Social History of Maoist China: Conflict and Change, 1949–1976 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 157.

- Bertil Lintner, China’s India War: Collision Course on the Roof of the World (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- Maurice Meisner, Mao’s China and After: A History of the People’s Republic (New York: Free Press, 1999), 300.

- Gregg Brazinsky, Winning the Third World: Sino-American Rivalry during the Cold War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 195–230.

- Matthew Galway, The Emergence of Global Maoism: China's Red Evangelism and the Cambodian Communist Movement, 1949–1979 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2022), 58, 67.

- Galway, The Emergence of Global Maoism, 74–75.

- Brazinsky, Winning the Third World, 195–230.

- Odd Arne Westad, The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 119; and Mark Atwood Lawrence, The Vietnam War: A Concise International History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 68–82.

- Galway, The Emergence of Global Maoism, 55–84, 137–99; and Xiaobing Li, The Dragon in the Jungle: The Chinese Army in the Vietnam War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

- Meyskens, Mao’s Third Front, 4–10.

- Meyskens, Mao’s Third Front, 43–47, 73, 84; and Guowuyuan sanxian jianshe tiaozheng gaizao guihua bangong shi sanxian jianshe (Beijing, 1991), 15–16.

- Meyskens, Mao’s Third Front, 22, 2933.

- Li Danhui and Xia Yafeng, Mao and the Sino-Soviet Split, 1959–1973 (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2018), 273–88.

- Robeson Frazier, The East Is Black: Cold War China in the Black Radical Imagination (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 202; Li, The Dragon in the Jungle; and Xiaobing Li, Building Ho’s Army: Chinese Military Assistance to North Vietnam (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2019).

- Meyskens, Mao’s Third Front, 140–48.

- Meyskens, Mao’s Third Front, 148–53.

- Meyskens, Mao’s Third Front, 227–368.