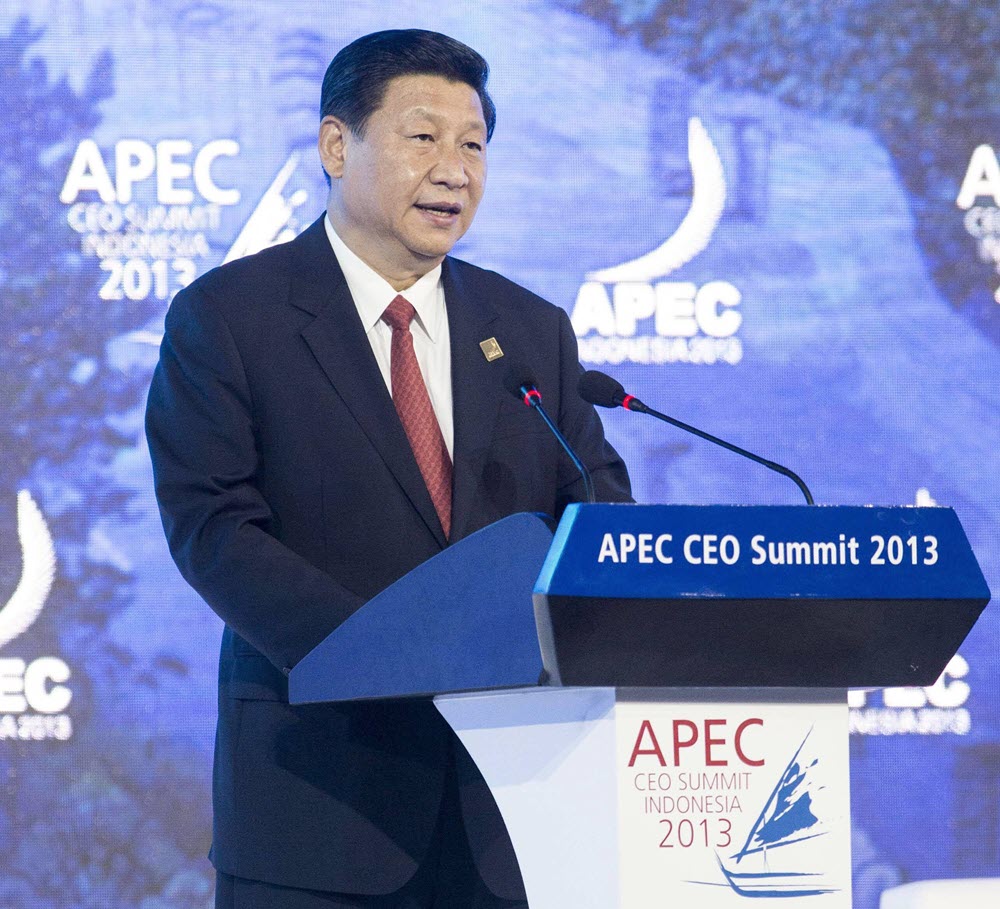

The geopolitical significance of the Pacific and Indian Oceans has been a prominent issue in the Chinese political and diplomatic discourse. In 2013, Xi Jinping called on leaders at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Economic Leaders’ Meeting to “firmly move toward the goal of constructing a common destiny of the Asia-Pacific,” a vision he has since advocated for repeatedly during diplomatic engagements with APEC state leaders.1 With the concept of the “Indo-Pacific,” the geopolitical chessboard of Asia is expanded to highlight the connection between the two oceans, fusing the region into a single geopolitical framework that encompasses multilateral security partnerships, economic and trade integration, and a structure of strategic competition for regional players to balance each other’s influence.

China’s strategic community of policy experts, including those closely affiliated with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) foreign policy organs and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), have extensively analyzed the significance of the Indo-Pacific. Many leading Chinese experts at the time suspected that this concept of Indo-Pacific, which shifted from “Asia-Pacific” to highlight the geostrategic value of the Indian Ocean, would quickly gain traction in the foreign policy of its geopolitical rivals and their close allies, creating new security challenges for China. Over the past decade, the Chinese strategic community has perceived this concept as a geostrategic response to China’s rise—a foreign policy instrument through which the United States, its allies, and partners can shape the security environment around China in their favor. Given the security and economic importance of the region, examining how Chinese strategists understand the Indo-Pacific as a geopolitically competitive space lends essential insight into how China perceives its strategic priorities in the context of security competition with regional countries.

Drivers of the Shift: The Geopolitical Significance of the Indian Ocean

Following then prime minister Shinzo Abe’s speech to the Indian parliament in 2007, the concept of Indo-Pacific gradually gained significance in Japanese and Australian strategic discourse. After Abe’s speech, Chinese strategic thinkers occasionally referred to the new “free and open Indo-Pacific” concept. Still, they did not immediately consider Japan’s goal to bring about the Indo-Pacific concept.2 The geopolitical assessment of connecting the Indian Ocean to Asia’s political landscape came a few years later when the United States began referring to the same concept in the early 2010s. Four drivers stood out in several oft-cited papers by well-connected Chinese scholars: (1) the shifting strategic center of gravity to the East, (2) the growing military and economic importance of the Indian Ocean, (3) the United States’ strategic demand to maintain influence in the Pacific, and (4) regional countries’ pursuit of elevated status through U.S. support.

In a 2013 article, Zhao Qinghai of the China Institute of International Studies, a research institute directly governed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, stated that the “strategic center of gravity” (shijie zhanlue zhongxin) is moving to the East because of the vital economic importance of the Indo-Pacific region, which serves as the “powerhouse of the global economy.”3 Zhao further noted that in terms of geopolitics, the Indo-Pacific has nine of the ten largest ports and seven of the ten largest militaries, making it an unusually dynamic and intricate security environment. The geography would allow a rising India to project its military power to the region by collaborating with Western countries that seek to use India to balance against China’s maritime expansion.4

Liu Zongyi of another state-sponsored think tank, the Shanghai Institute of Imnternational Studies, similarly noted that India is in a naturally advantaged position to leverage the vital geopolitical importance of the Indian Ocean.5 Two-thirds of the world’s maritime oil transport flows through the Indian Ocean, which holds several maritime chokepoints, including the Straits of Hormuz, Malacca, and the Bab al-Mandab.

Wu Zhaoli at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences also argued that the Indian Ocean “has already been incorporated in the grand strategic thinking of the traditional East Asian states,” citing their dependence on imported oil.6 As a result, the growth of Chinese and Indian naval power and the expansion of the two countries’ maritime interests resulted in an “intensifying strategic competition that drives the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean as a connected body.”7

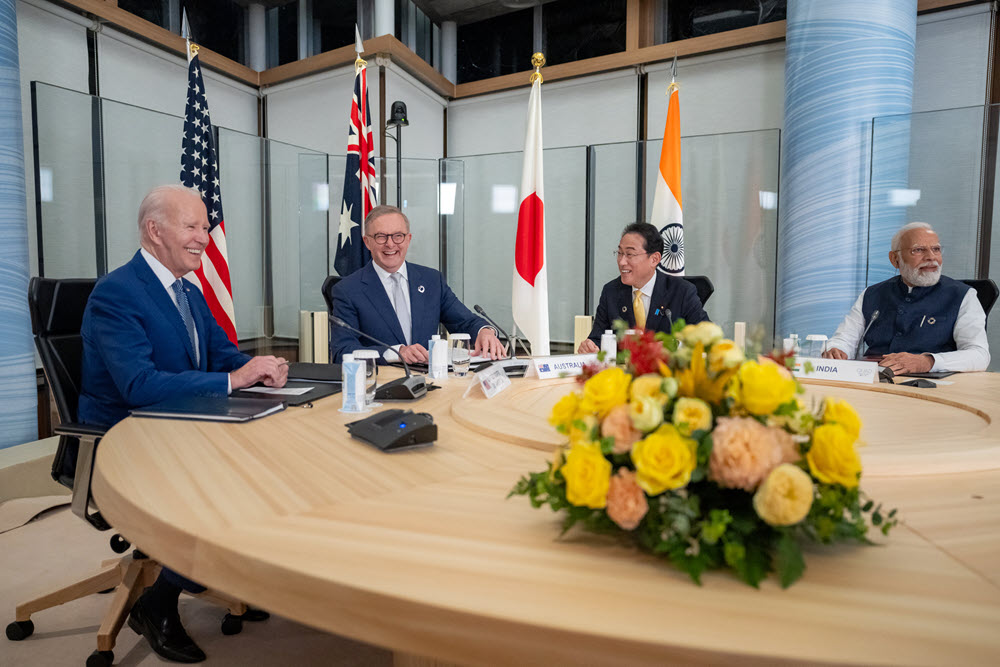

Given the geostrategic importance of the Indian Ocean, Chinese strategists are concerned that the emergence of the concept would reinforce U.S. power in the region. They believe that this construct would enhance the U.S. strategic position in the region through minilateral security cooperation and regional economic integration with liberal economies, particularly India and Australia.8 By boosting India’s prominence in the western Pacific through security cooperation like the Quad (comprising Australia, India, Japan, and the United States), the United States could fulfill the need to create its “strategic space” and defend against China.9

Furthermore, Chinese experts pointed out that the shift to the Indo-Pacific framework serves the interests of regional U.S. partners. By highlighting their geopolitical positions to the United States, these countries can “elevate their status” in the region and “tie the United States down” in the Indo-Pacific for a long-term security guarantee.10 Australia, for instance, actively promoted the Indo-Pacific framework to signal its geostrategic importance to U.S. interests in exchange for continued U.S. security assistance to counter Chinese influence.11 Therefore, from the Chinese point of view, the “Indo-Pacific project” is partly driven by individual state interests that can be advanced by locking in U.S. involvement in the region. Note that the “individual state interests” do not necessarily align with the United States’ strategic priorities and could change over time. This could be the perceptual underpinning of China’s confidence in employing a “wedging” strategy to separate U.S. allies and partners.

Perception of Encirclement and Containment

If the Indo-Pacific as a geostrategic project was born with the overtone of geopolitical competition, the Chinese perception of this project’s motives is a deciding factor in how China assesses the security of its strategic space. President Xi Jinping’s recent speeches make clear that the official Chinese position depicts Western powers as relentless interventionists actively suppressing China’s growth and entirely responsible for the deterioration of the country’s external environment.12 During the 2023 “two sessions,” he claimed that the “Western countries led by the United States have implemented all-around containment, encirclement, and suppression,” thereby creating “unprecedented severe challenges to our country’s development.”13

Not surprisingly, the same perception of containment and encirclement can be observed in the writings of influential Chinese authors. Indeed, well-connected scholars in the Chinese strategic community often must toe the party line under Xi’s rule. Yet the idea of seeing the United States as intending to contain China has been ingrained in Chinese strategic discourse since the end of the Cold War, indicating some level of genuine belief among the strategic studies community.14 For instance, Wu Zhaoli, writing in 2013, categorized the then nascent “Indo-Pacific vision” as an attempt to “contain China’s influence in the Indo-Pacific region, especially in the Indian Ocean.”15 Xia Liping, a well-connected scholar with affiliations with the State Council Development and Research Center, the Taiwan Affairs Office, and the PLA’s Nanjing Military Academy, described the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy as an attempt to expand the hub-and-spoke security system to the Indian Ocean to contain China’s. He envisioned that the previous “Asia-Pacific” framework was “missing a half” on the west side when only Japan and Australia were anchors of the hub-and-spoke system.16 The expansion of the system to India and the Indian Ocean would create “a large arc-shaped network of allies and partners that surrounds the East Asian continent, with Japan and India balancing and pinning China from both west and east” and give “the United States a geostrategic advantage.”17

More recently, the Biden administration released the Indo-Pacific Strategy in 2022, doubling down on the commitment to regional allies and partners while reversing some of the “America first” policies that were considered counterproductive to alliance cohesion during the Trump administration.18 This has only reinforced the conviction that the Indo-Pacific strategy was focused on containing China.19 As Fan Gaoyue, a retired PLA senior colonel who previously taught at the PLA Academy of Military Sciences, put bluntly, the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy “is fundamentally intended to make India the front line of containing China…[to] stop China’s rise and preserve the American global hegemony.”20 Fan’s conviction seems universal in the Chinese strategic community. The inclusion of the Indian Ocean in the arc of containment only reinforces the widely shared view that the Indo-Pacific strategy is further compressing China’s strategic space.

Incorporating the Indo-Pacific into Strategic Discourse

Despite seeing the Indo-Pacific from a containment angle, Chinese strategic thinkers nevertheless express confidence that China can safely exploit the weaknesses and immaturity of this geopolitical construct. This stems from the perception that the key U.S. partners may not always be on board with the United States in encircling China because they have individual economic and trade ties with China that are too costly to cut.

Chinese experts frequently point to the “domestic disagreements” with which countries like India, Australia, and Japan must contend as what may hamstring the development of the Indo-Pacific concept. Specifically, when the concept was gaining prevalence, Chinese strategists doubted whether Australia and India were entirely determined to join forces with the United States to balance against China. They cited India’s long preference for strategic autonomy and Australia’s economic interdependence with China, both of which have significant domestic political pull on these countries’ foreign policy.21 “India’s diplomatic strategy of placing bets on both the United States and China will make the U.S. Indo-Pacific geostrategic construct unattainable,” Liu Zongyi stated.22 Similarly, Wu Zhaoli argued that if the United States “excessively emphasizes the geopolitical aspects of the Indo-Pacific but ignores the intrinsic economic trends in the region, it will only create doubts and concerns in the Australian and Indian strategic communities.”23

Indeed, Chinese writings published during Xi Jinping’s third term affirmed these earlier views. Since 2018, several influential Chinese scholars at state-sponsored think tanks have argued that any explicit leaning toward the United States will create difficult strategic tradeoffs for India and Australia, which must balance their economic relations with China and their security assistance from the United States.24 These countries’ participation in agreements on regional economic integration is often cited as evidence that key U.S. partners have diverse strategic interests that do not fully align with those of the United States, creating challenges for incorporating the Indo-Pacific concept into their respective strategic priorities.

Going forward, China’s foreign policy could reflect what Fan Jishe at the CCP Central Party School describes as “shaping [the U.S. allies’] policies and behaviors” through China’s “relatively complex political, economic, and diplomatic ties with these countries.”25 While some Chinese scholars assess that aligning with the United States could be an increasingly attractive strategic option for India as its economic and military rivalry with China intensifies, most express little concern with the Indo-Pacific concept becoming a successful U.S.-led “united front” against China.26

Conclusion

In the past decade, Chinese strategic thinkers have closely examined the emergence of the Indo-Pacific as a geostrategic construct through which the United States and its regional partners can advance their geopolitical interests in Asia. The strategic community’s attention to the role of India and the Indian Ocean may point to the regime’s renewed efforts to strengthen its geopolitical position and reduce China’s vulnerabilities, such as energy dependence and insufficient force projection over maritime chokepoints. Given the military and economic significance of the Indian Ocean, China will likely expand its economic influence over the Indo-Pacific region and prioritize the force-projection capabilities of its naval assets in the near future.

Furthermore, this essay’s assessment of the Chinese strategic community reveals a sobering thought on understanding strategic thinking in China. By mapping how Chinese strategic thinkers perceive and assess the emergence and construction of the Indo-Pacific, we know that the Chinese view of this concept, while uniformly focusing on geostrategic containment and encirclement, indicates a level of confidence that China can leverage the disparate strategic interests and the economic dependence on China among key U.S. partners to counter the attempts to deny its rise.

What is missing, however, is a reflection or assessment of how China’s behavior is perceived by these countries and whether China appears to be an attractive partner and neighbor. The absence of self-reflection likely results from President Xi Jinping’s relentless push of the CCP’s narrative of victimhood and the increasingly pervasive influence of nationalism. As the party continues to use external threats to justify the legitimacy of its leadership, it must install a hostile image of Western powers and police any thinking that could implicate China’s role in fueling an adverse security environment. This encourages an echo chamber in the strategic studies community and can erode any remaining self-correcting functions once supported by Chinese scholars, both civilian and military.27

Whether Xi believes that the Western powers are indeed bent on seeing China’s fall may not matter. The fact that he publicly repeats this (even if out of political and institutional necessity) is sufficient to discourage the strategic community from serving any self-correcting role within elite foreign policy circles. As such, when China’s behavior persists in appearing more coercive than cooperative, it may drive countries closer to the United States, encouraging them to reduce or eliminate any economic interdependence with China. Paradoxically, the perception of containment and the ensuing aggressive actions that are only perceived as “defensive” by Chinese elites could further convince regional countries to engage in security integration with the United States.

Elliot S. Ji is a PhD candidate in the Department of Politics at Princeton University.

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

ENDNOTES

- Xi Jinping, “Xi jin ping zai ya tai jing he zu zhi gong shang ling dao ren feng hui shang de yan jiang” [Xi Jinping’s Speech at the APEC Economic Leader’s Meeting], Xinhua, October 8, 2013, http://www.xinhuanet.com/world/2013-10/08/c_125490697.htm; and Xi Jinping, “Tuan jie he zuo yong dan ze ren gou jian ya tai ming yun gong tong ti—zai ya tai jing he zu zhi di er shi jiu ci ling dao ren fei zheng shi hui yi shang de jiang hua” [Cooperate in Solidarity to Take Responsibility, Building a Shared Destiny of the Asia-Pacific—a Speech at the 29th APEC Economic Leader’s Meeting], Gazette of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), November 18, 2022, https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2022/content_5729414.htm.

- For limited Chinese reactions to Abe’s speech, see Shu Biquan, “Ri ben hai yang zhan lüe yu ri mei tong meng fa zhan qu shi yan jiu” [A Study on Japan’s Maritime Strategy and Development Trends in the Japan-U.S. Alliance], Pacific Journal 19, no. 1 (2011): 90–98; and Jin Xide, “Ri yin an quan xuan yan yu ‘jia zhi guan wai jiao’” [Japan-India Joint Security Statement and “Value Diplomacy”], Contemporary World, no. 12 (2008): 29–31.

- Zhao Qinghai, “‘Yin tai’ gai nian ji qi dui Zhong guo de han yi” [The Concept of “Indo-Pacific” and What It Means for China], Contemporary International Relations, no. 7 (2013): 17.

- Ibid., 18.

- Liu Zongyi, “Chong tu hai shi he zuo?—‘Yin tai’ di qu de di yuan zheng zhi he di yuan jing ji xuan ze” [Conflict or Cooperation?—Geopolitical and Geoeconomic Choices in the Indo-Pacific Region], Indian Ocean Economic and Political Review, no. 4 (2014): 4–20.

- Wu Zhaoli, “‘Yin tai’ de yuan qi yu duo guo zhan lüe bo yi” [Indo-Pacific: Origins and Multinational Strategy Game], Pacific Journal 22, no. 1 (2014): 33.

- Lin Minwang, “‘Yin tai’ de jian gou yu ya zhou di yuan zheng zhi de zhang li” [The Construct of ‘Indo-Pacific’ and the Pull of Asian Geopolitics], Foreign Affairs Review 35, no. 01 (2018): 20.

- Zhao, “‘Yin tai’ gai nian ji qi dui Zhong guo de han yi,” 16; Wei Zongyou, “Mei guo yin tai zhan lüe yan bian qu shi ji ying xiang ping gu” [The Evolution and Impact of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy], Frontiers, no. 5 (2021): 92–100; and Ye Hailin and Li Mingen, “Mei guo ‘yin tai zhan lüe’ de tiao zheng yu zhong guo zhou bian wai jiao de yin ying” [The U.S.’ Adjustment of Its ‘Indo-Pacific Strategy’ and the Response of China's Neighbourhood Diplomacy], Journal of Latin American Studies 45, no. 1 (2023): 28–49, https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail//11.1160.c.20230228.1006.002.html.

- Zhang Guihong, “‘Yi dai yi lu’ chang yi yu yin tai zhan lüe gou xiang de bi jiao fen xi” [Belt and Road Initiative vs. Indo-Pacific Strategy], Contemporary International Relations, no. 2 (2019): 33.

- Zhao, “‘Yin tai’ gai nian ji qi dui Zhong guo de han yi,” 19.

- Zhang Li, “‘Yin tai’ gou xiang dui ya tai di qu duo bian ge ju de ying xiang” [The Indo-Pacific Approach: Implications for Asia-Pacific Regional Multilateral Scenario], South Asian Studies Quarterly, no. 4 (2013): 1–7.

- Bonny Lin et al., “China’s 20th Party Congress Report: Doubling Down in the Face of External Threats,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 19, 2022, https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-20th-party-congress-report-doubling-down-face-external-threats.

- Keith Bradsher, “China’s Leader, With Rare Bluntness, Blames U.S. Containment for Troubles,” New York Times, March 7, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/07/world/asia/china-us-xi-jinping.html.

- This perception was salient as Chinese scholars observed U.S. and NATO military operations in Kosovo and Afghanistan. For early evidence of the view of containment, see the PLA research on lessons learned from the Kosovo War. Xu Guang and Li Zhengguo, eds., Ke suo wo zhan zheng yan jiu [Research Into Kosovo War] (Beijing: PLA Press, 2000).

- Wu, “‘Yin tai’ de yuan qi yu duo guo zhan lüe bo yi,” 35.

- Xia Liping, “Di yuan zheng zhi yu di yuan jing ji shuang zhong shi jiao xia de mei guo ‘yin tai zhan lüe’” [U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy: Geopolitical and Geoeconomic Perspectives], Chinese Journal of American Studies 29, no. 2 (2015): 37.

- Ibid., 37.

- The White House, “Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States,” February 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf.

- Several Chinese articles review the evolution of U.S. strategy in the Indo-Pacific. See, for example, Huang He, “Mei guo di yuan zheng zhi zhan lüe yan bian zhong de e zhi si wei: Cong‘xuan ze xing e zhi’ dao ‘yin tai zhan lüe’”[The Containment Thinking in the Evolution of American Geopolitical Strategy: From “Selective Containment’” to “Indo-Pacific Strategy”], Journal of Shenzhen University (Humanities & Social Sciences) 35, no. 1 (2018): 72–78.

- Fan Gaoyue, “Mei guo yin tai zhan lüe ji qi shi shi yu ying xiang” [American Indo-Pacific Strategy and Its Implementation and Influence], Northeast Asia Economic Research 5, no. 2 (2021): 102.

- Wu, “‘Yin tai’ de yuan qi yu duo guo zhan lüe bo yi,” 39; Xia, “Di yuan zheng zhi yu di yuan jing ji shuang zhong shi jiao xia de mei guo ‘yin tai zhan lüe,’” 48; and Song Wei, “Cong yin tai di qu dao yin tai ti xi : yan jin zhong de zhan lüe ge ju” [From Indo-Pacific Region to Indo-Pacific System: The Strategic Framework in Evolution], Pacific Journal 26, no. 11 (2018): 33.

- Liu, “Chong tu hai shi he zuo?” 15.

- Wu, “‘Yin tai’ de yuan qi yu duo guo zhan lüe bo yi,” 39.

- Mei guo yin tai zhan lüe ji qi shi shi yu ying xiang,” 106–8; Ye and Li, “Mei guo ‘yin tai zhan lüe’ de tiao zheng yu zhong guo zhou bian wai jiao de yin ying; and Zhang Weiwei, “Zhan lüe fen xi shi jiao xia de bai deng zheng fu ‘yin tai zhan lüe’” [The Biden Administration’s Indo-Pacific Strategy from the Perspective of Strategic Analysis], Peace and Development, no. 2 (2022): 39.

- Fan Jishe, “Cong ya tai dao ‘yin tai’: mei guo di qu an quan zhan lüe de bian qian yu hui gui” [From Asia-Pacific to Indo-Pacific: The Evolution and Return of U.S. Regional Security Strategy], Journal of International Security Studies 40, no. 5 (2022): 52.

- See, for example, Zhao Pu and Li Wei, “Ba quan hu chi : mei guo ‘yin tai’ zhan lüe de sheng ji” [Sustaining Hegemony: The Upgrade of the U.S. “Indo-Pacific Strategy”], Northeast Asia Forum 31, no. 4 (2022): 40–41.

- For a recent analysis of the echo chambers and the information challenge of authoritarian rule, see Tong Zhao, “How China’s Echo Chamber Threatens Taiwan: Xi Jinping Has Unleashed Hawkish Forces He Can't Control,” Foreign Affairs, May 9, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/taiwan/-china-echo-chamber-threatens-taiwan.