This is the introduction to the report “Mapping China’s Strategic Space.” To read the full report, download the PDF.

In September 1939, merely two weeks after Germany’s invasion of Poland, a group of leaders from the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) met with Assistant Secretary of State George Messersmith. The State Department’s policy planning capacity was nonexistent at the time, and CFR leaders offered to help the U.S. government prepare for the postwar world. Staunch internationalists, CFR members believed in greater U.S. involvement and leadership in world affairs, commensurate with the country’s growing economic power. With the State Department’s approval and the Rockefeller Foundation’s financial support, CFR officially launched a project named “Studies of American Interests in the War and the Peace,” aimed at examining the war’s effects on the United States and developing concrete proposals to safeguard U.S. interests once peace again prevailed. During the subsequent five years, several hundred U.S. leaders and experts from civil society, academia, business, and government, organized in five focused study groups, participated in over three hundred meetings and produced close to seven hundred reports dispatched to the State Department and the White House.1

In July 1941, CFR’s Economic and Financial Group completed a study introducing the concept of a “grand area” comprising most of the non-German world and including the “Western Hemisphere, the United Kingdom, the remainder of the British Commonwealth and Empire, the Dutch Indies, China and Japan.” 2 Based primarily on calculations of the need for continued U.S. access to export markets, as well as to raw materials and other products necessary to maintain a maximum defense effort, the definition of a quasi-global geographic sphere of U.S. interests also had military implications. As the report noted: “The United States should use its military power to protect the maximum possible area of the non-German world from control by Germany in order to maintain for its sphere of interest a superiority of economic power over that of the German sphere.” 3 In a world threatened by totalitarian mass conquest, the initial quest for sustained economic defense led U.S. planners to leap “from a hemispheric to a global mental map of U.S. interests and responsibilities,” a shift “which has proved enduring in the eight decades since.”4

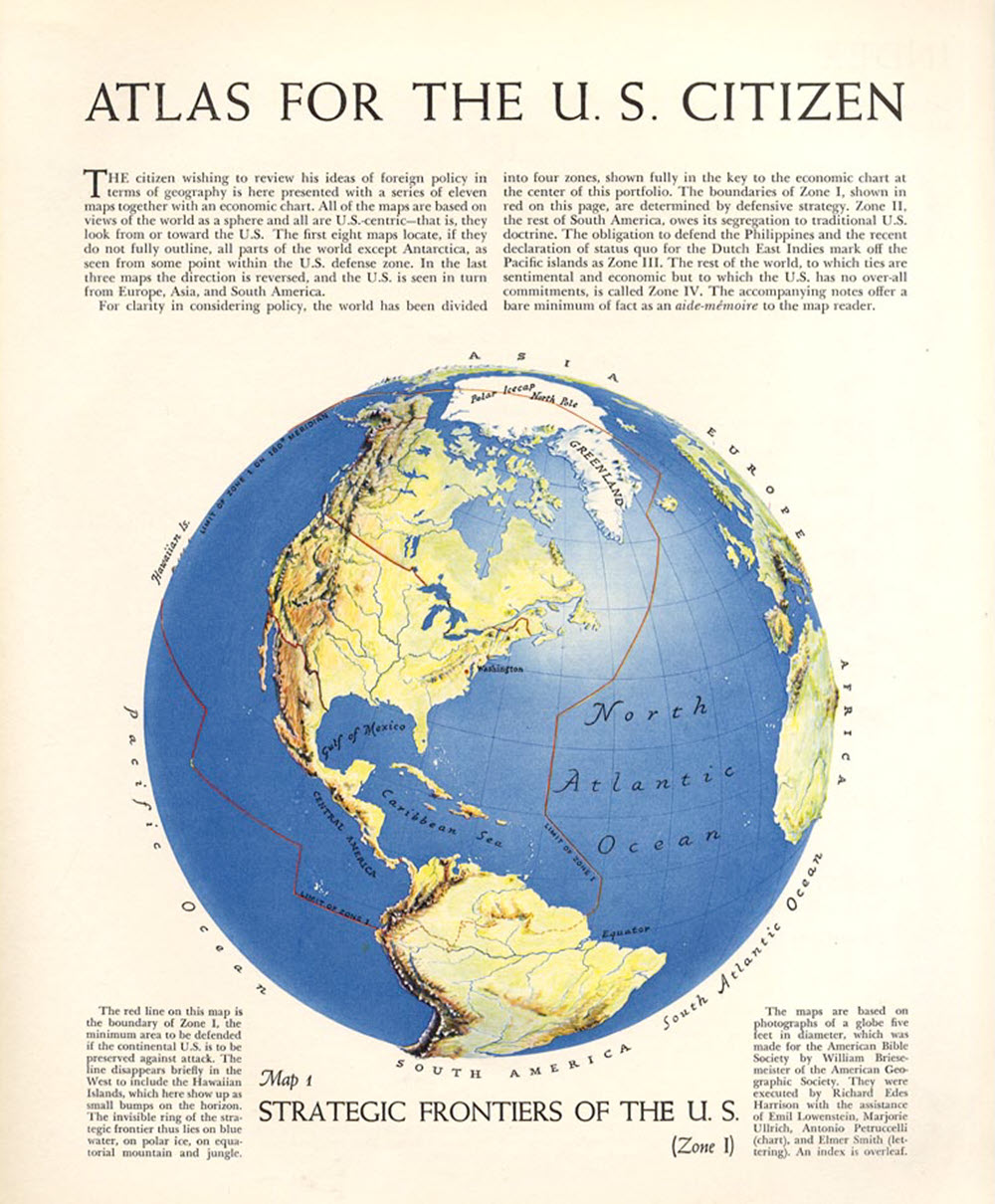

Richard Edes Harrison, “Strategic Frontiers of the U.S.,” Fortune, September 1940, https://www.fulltable.com/vts/f/fortune/aac/0nnt6.jpg.

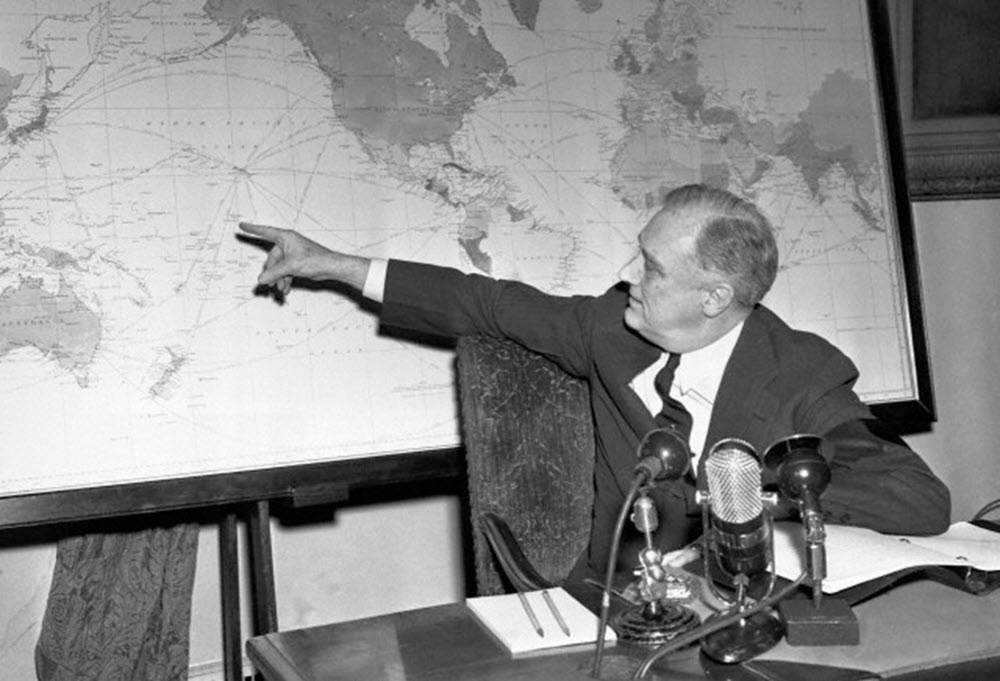

Richard Edes Harrison, “Strategic Frontiers of the U.S.,” Fortune, September 1940, https://www.fulltable.com/vts/f/fortune/aac/0nnt6.jpg.  Franklin D. Roosevelt, February 23, 1942: “I want to explain to the people something about geography—what our problem is and what the overall strategy of the war has to be.” http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FDR-Map-1942.jpg.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, February 23, 1942: “I want to explain to the people something about geography—what our problem is and what the overall strategy of the war has to be.” http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FDR-Map-1942.jpg.

Such discussions of a U.S. “grand area” are not as incongruous in a study pertaining to China’s “strategic space” as one might think. Just like their U.S. counterparts in the early 1940s, Chinese strategists since the mid-1980s have been primarily concerned about the definition of a grand area necessary to ensure their country’s survival and enduring development—a sphere of interest where they would strive to maintain superiority, which they call China’s “strategic space” (zhanlüe kongjian). They too envision enlarged mental maps of interests and responsibilities, and their spatial horizons have over time expanded to the global and even beyond. Both the United States’ “grand area” and China’s “strategic space” deliberations evolved into a proactive, outward- directed endeavor from an initially defensive perspective developed in the face of a perceived existential threat. For the United States, these discussions took place in the context of an ongoing war, with totalitarian powers on the march, engaged in territorial conquest, seizing control of resources, and actively threatening to destroy friendly European and Asian powers, and potentially eventually the United States. For China, the perceived existential threat takes the form of a hostile U.S. global hegemon, which, even at a time of ostensibly friendly cooperative relations, is seen through the lenses of regime insecurity as bent on ideological subversion, economic suppression, and military encirclement. Finally, both grand area and strategic space discussions took place during a period when U.S. and Chinese elites came to believe that their country was experiencing a dramatic increase in its relative material power and sought to obtain an advantageous, even dominant, long-term geostrategic position for their nation once the major existential threat had been beaten back. In sum, similar to the grand area idea, the concept of strategic space is truly about China’s accession to great-power status and pursuit of global primacy.

As ever, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of open-source research when examining emergent strategic concepts in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This report is based on publicly available Chinese-language writings primarily published by military and academic thinkers over the last 40 years and does not include government archives nor personal interviews. As such, it only presents one sliver of what is undoubtedly a bigger, more complex picture involving, among others, government and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders, and is therefore incomplete. In addition, it may be difficult to ascertain the connection between the experts involved in these discussions and the highest political decision-making echelons. However, most of the strategic thinkers cited in this report can be categorized as workers of the state simply because the entities they belong to are organically linked to either Chinese state or CCP organs. Some participants in these deliberations explicitly describe as their main duty serving the leadership’s development of a grand strategy. Nonetheless, these discussions about strategic space are not hosted within a single government-endorsed task force, with an explicit mission to fill in for the state’s planning capacity; rather, they are the product of a massive officially endorsed collective intellectual effort evidently designed to inform the leadership’s deliberations and to support and elaborate on its basic decisions. The participants in these discussions advance like a school of fish—each of them distinct and emanating from different centers across the system, but generally moving in parallel in a similar direction over time. Finally, despite limited exceptions, it is impossible to determine who influenced whom in the process, and whether specific intellectual interests, directions of enquiries, themes, or formulations emerge from government bureaucracies or party organs behind closed doors before they are picked up by intellectuals, or the other way around. It is possible that these interactions are horizontal rather than vertical, and that political and intellectual spheres are constantly interacting via channels hidden to the public eye and mutually nourishing each other’s thinking. The reality of the challenges described above must be recognized—not as a way to dismiss the body of work presented here but as an encouragement to further research.

Although imperfect, the preliminary examination of the strategic space concept introduced by this report illuminates how Chinese elites conceive of an imagined realm well beyond China’s national borders in a way that was previously unthinkable due to the country’s relative weakness. As such, this study serves as an early warning of the future direction in which China’s foreign policy may be headed as its power grows.

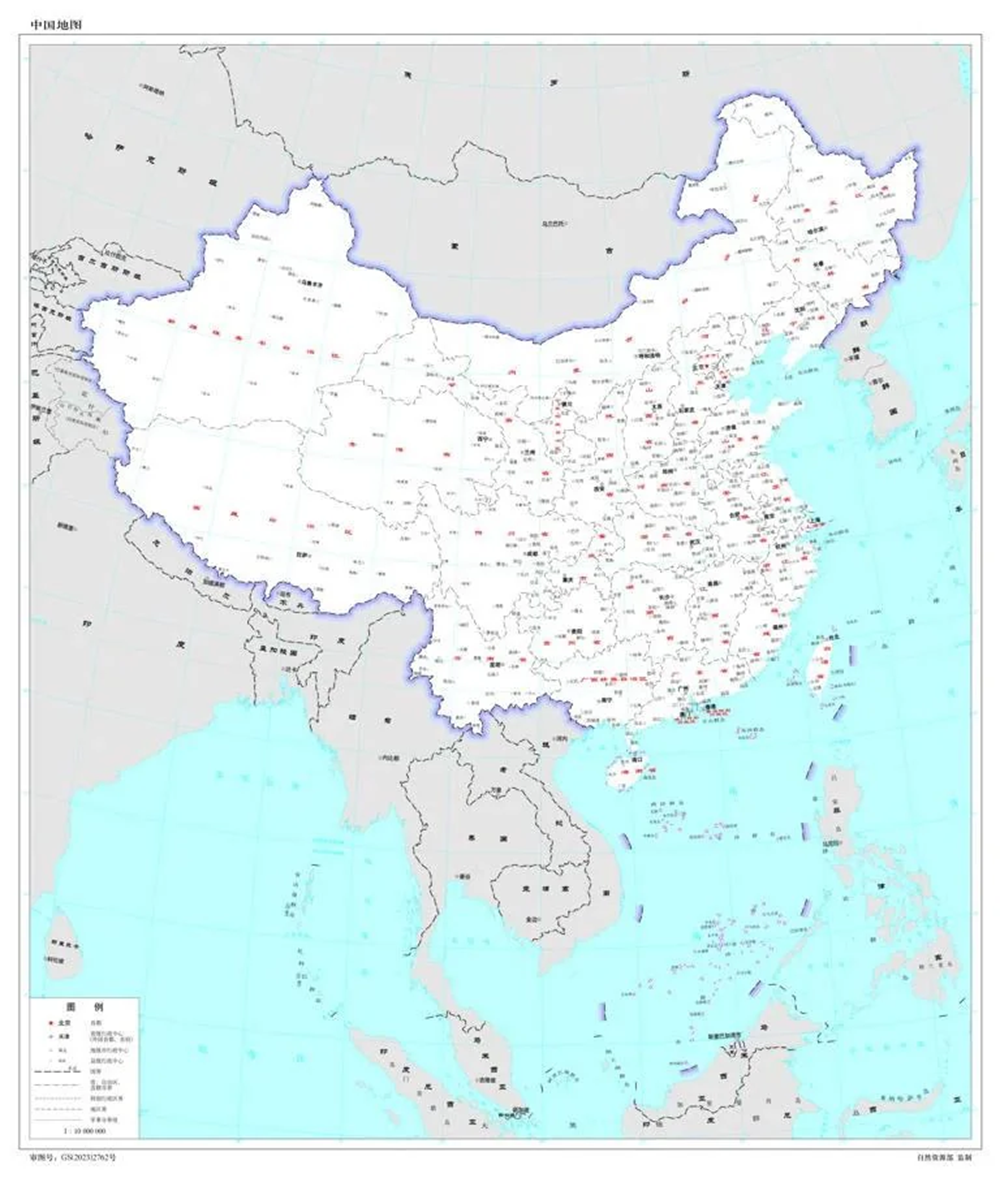

What is under scrutiny is not the recovery of territories lost with the collapse of the Qing empire depicted in “national humiliation maps” or what William Callahan poetically describes as a process of “re-membering”—the re-attachment of previously dismembered limbs to China’s national “geobody” that would eventually reconcile the tension between past unbounded imperial domain and present sovereign nation-state territory.5 In addition to the well-documented, ongoing aggressive behavior exhibited by the PRC in the South and East China Seas and in the Taiwan Strait, recent manifestations of this desire to incorporate disputed territories as its own include the 2023 release of the PRC’s new “standard” map reaffirming Beijing’s claims to sovereignty over both maritime features in the South China sea and around Taiwan, as well as land in the Himalayas and at the border with Russia;6 the regularly updated list of rectified toponyms in disputed areas;7 and the passing of the 2021 Land and State Boundary Law whose language leaves open the possibility of future effective control through construction or occupation.8 Although the PRC’s territorial claims are far from negligible, they are not the main concern of the contemporary strategic thinkers examined in this study. Their strategic horizons do not stop at China’s borders; rather, what they have in mind is a global map of China’s expanded power.

2023 PRC Standard Map published by the Ministry of Natural Resources.

2023 PRC Standard Map published by the Ministry of Natural Resources.

Unpacking the strategic space concept and observing how it has evolved since it first emerged in the mid-1980s brings to light the significance of spatial considerations and the deep-seated influence of classical geopolitics on contemporary Chinese strategic thinking. Descriptions of China’s expansion as an existential, inevitable process suggest a vision of the state that echoes early twentieth-century European geopolitik. This system of thought portrays the state as analogous to an organism that has to struggle for space to survive within a world fraught by intense competition.pdf.9 Chinese contemporary geopoliticians do not go as far as their European forebearers in advocating territorial acquisitions to secure mineral and agricultural resources, but anthropomorphized undertones are reflected in their use of imageries of “choked” and “squeezed” spaces and claims about the need of expanded space for national “survival and growth.” The pervasive influence of classical geopolitics is also apparent in discussions about great-power containment schemes, the strategic advantages conferred to maritime versus continental powers, and the quest for “new frontiers” as desirable extensions of an existing space deemed too constricted for comfort. Geopolitical conceptualizations also take the form of friendly or hostile variable geometries of lines, arcs, circles, spheres, pan-regions, peripheries, and cores. More recent strands of discussion seem to converge toward the definition of a realm unbound by territorial borders and framed in civilizational terms, in which imperial resonances can be found. As Oxford professor Vivienne Shue hypothesizes, “an updated ideal of imperial China and of China as an empire could be what [is] actually inhabiting political imaginations in Beijing.”10

To paraphrase Sir John Robert Seeley’s infamous 1883 essay in which he rejected the concept of a “little England” in favor of a “greater Britain” whose history is “not in England but in America and Asia,” the foundation of a “greater China” is not happening “in a fit of absence of mind” but has been hashed over by a diligent intellectual hivemind for several decades.11 Leaders of the collective brain that includes geographers, international relations specialists, and practitioners appear to belong predominantly to military and national security circles. These thinkers seem to wield enough influence within the party-state system that their ideas end up reverberating and, at times, eventually being endorsed at the highest political level.

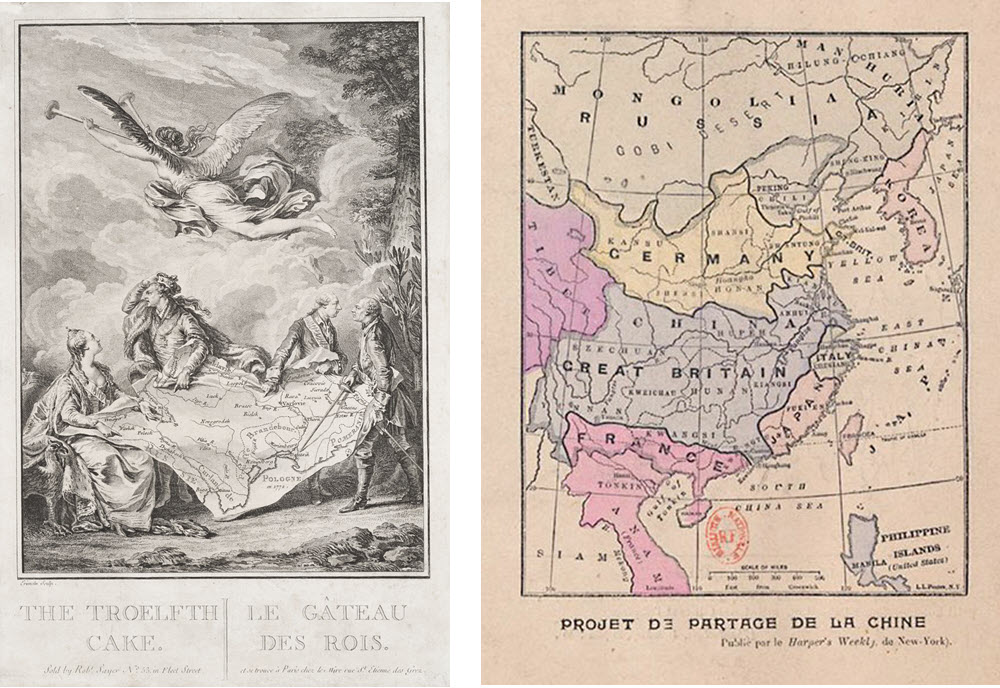

Of course, the significantly expanded Chinese strategic space they collectively describe still exists mainly in the depths of their imaginations. But the mental maps they are delineating could anticipate a desired future reality that aligns with another dream expressed by Xi Jinping himself—that of China’s great resurgence.12 After all, as John Brian Harley writes, lands were “claimed on paper before they were effectively occupied,” and in this sense “maps anticipated empire.” 13 Even if contemporary strategists do not publicly display any intention of reproducing European precedents and carving up the world both on paper and on the ground,14 their imaginary strategic space maps reflect their intimate beliefs about China’s proper place in the world—not its localization in world geography, but its “rightful place” at the center of the world and at the top of the international system.

“The Troelfth Cake – Le gâteau des rois,” 1773, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Allegory_of_the_1st_partition_of_Poland.jpg.

“The Troelfth Cake – Le gâteau des rois,” 1773, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Allegory_of_the_1st_partition_of_Poland.jpg.

“A Forecast of the Partition of China,” Harper’s Weekly, July 4, 1900, https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/boxer_uprising/bx_essay02.html.

Demarcating China’s strategic space is therefore really an exercise in “re-centering” China to reflect the rise of its power and the shift of the world’s center of gravity from the Atlantic to the Asia-Pacific. Whether candidly acknowledged as a result of China’s self-confidence in its growing power, or half-heartedly concealed so as not to bear the abominated stain of imperialism, the degree of Beijing’s ambitions is unmistakable. It appears in plain sight in the novel planisphere projections that Chinese Academy of Sciences geographer Hao Xiaoguang has been working on since the early 2000s. Hao’s vertical map, which centers the Southern Hemisphere on China and pushes the United States to the periphery, was officially adopted in 2013 and has since been displayed in classrooms throughout the country.15

Looking back 40 years, it in hindsight is possible to discern three overlapping waves of focused intellectual interest that have accompanied the maturation of the idea of an expanded strategic space for China and its subsequent execution at the political level. These periods are examined sequentially in the core chapters of this report. After a first section that examines the emergence of the “strategic space” concept, its definition, and eventual propulsion into officialdom in 2013, the second chapter considers how Chinese intellectual elites reinvested in geopolitics at the end of the Cold War and the lessons they learned from a discipline long considered as toxic because of its association with imperialism. The turn of the century marks the beginning of a second period, a “golden decade” during which PRC analysts were absorbed by the concept of power. The third chapter follows their deliberations in lockstep as they attempt to define China’s core interests, ponder its maritime and continental geopolitical nature, learn from successes and failures of past rising powers, and assess how to position China relative to other great powers. As they grew increasingly confident about their country’s ascending trajectory as well as increasingly apprehensive about its security environment, Chinese strategic thinkers began developing a new grammar of expansion and delineating more precisely the extended contours of China’s strategic space, a process that is revealed in chapter 4. The concluding chapter explores whether and how the global pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and China’s most recent economic challenges have affected the mental map of China’s strategic space.

Nadège Rolland is Distinguished Fellow for China Studies at the National Bureau of Asian Research. Her NBR publications include China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative (2017), “China’s Vision for a New World Order” (2020), and “A New Great Game? Situating Africa in China’s Strategic Thinking” (2021).

Read the chapters online:

Introduction: Mapping China’s Strategic Space

Chapter 2: The Return of Geopolitics

Chapter 3: “Positioning” China: Power and Identity

Chapter 4: The Logic and Grammar of Expansion

Chapter 5: Conclusion: A New Map?

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

ENDNOTES

- This section draws heavily from G. William Domhoff, “The Council on Foreign Relations and the Grand Area: Case Studies on the Origins of the IMF and the Vietnam War,” Class, Race and Corporate Power 2, no. 1 (2014): 1–41.

- Ibid.

- Stephen Wertheim, “To the Grand Area and Beyond: The Sudden Transformation of the United States’ Strategic Space,” National Bureau of Asian Research, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, August 23, 2023, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/to-the-grand-area-and-beyond-the- sudden-transformation-of-the-united-states-strategic-space.

- Wertheim, “To the Grand Area and Beyond.” For an enlightening examination of the evolution of the U.S. conceptualization of its geostrategic space as reflected in 1940s map projections, see He Guangqiang, “Erzhan qijian Meiguo diyuanzhanlüe kongjian guannian bianqian: Jiyu ditu touying de shijiao” [The U.S. Geostrategic Space Concept’s Transformation during World War II: A Perspective Based on Map Projection], Scientia Geographica Sinica 39, no. 5 (2019).

- William A. Callahan, “The Cartography of National Humiliation and the Emergence of China’s Geobody,” Public Culture 21, no. 1 (2009): 141–73. See also John Agnew, “Looking Back to Look Forward: Chinese Geopolitical Narratives and China’s Past,” Eurasian Geography and Economics 53, no. 3 (2012): 301–14.

- The 2023 edition of the national map is available from China Daily at https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202308/28/ WS64ec91c2a31035260b81ea5b.html.

- “India Rejects China’s Renaming of 30 Places in Himalayan Border State,” Reuters, April 2, 2024; Ralph Jennings, “Why Is China Renaming Disputed Locations around Asia?” Voice of America, January 6, 2022; “Ziran ziyuan bu guanyu yinfa ‘gongkai ditu neirong biaoshi guifan’ de tongzhi” [Notice of the Ministry of Natural Resources on the Issuance of “Representation Standards for Public Maps Content”], State Council Information Office (PRC), February 6, 2023, https://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2023/content_5752310.htm.

- “The PRC’s Land Borders Law,” U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, October 23, 2023, https://www.pacom.mil/Portals/55/Documents/Legal/ J06%20TACAID%20-%20PRC%20LAND%20BORDERS%20LAW%20-%20FINAL.pdf?ver=zp6y0pfpaAWoL5KOv0KDYg%3D%3D.

- Christopher Hughes identified this trend in PRC domestic politics in his seminal article “Reclassifying Chinese Nationalism: The Geopolitik Turn,” Journal of Contemporary Chin 20, no. 71 (2011): 601–20.

- Vivienne Shue, “Re-imagining China (and China Studies) in the Post Post–Cold War” (keynote speech at Dansk Institut for Internationale Studier, Copenhagen, November 26, 2021), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WV04_SBGmLA. See also Vivienne Shue, “Regimes of Resonance: Cosmos, Empire, and Changing Technologies of CCP Rule,” Modern China 48, no. 4 (2022): 679–720.

- John Robert Seeley, “The Expansion of England,” 1883, available at https://web.viu.ca/davies/H479B.Imperialism.Nationalism/Seeley. Br.Expansion.imperial.1883.htm.

- Emmanuel Dubois de Prisque, “La cartographie en Chine du ‘rêve chinois’ à la réalité géopolitique” [Chinese Cartography from the ‘China Dream’ to Geopolitical Reality], Outre-Terre 1, no. 38 (2014).

- John Brian Harley, “Maps, Knowledge, and Power,” in The Iconography of Landscape: Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design, and Use of Past Environments, ed. Denis Cosgrove and Stephen Daniels (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 277–312.

- The imagery of China being “carved up like a watermelon” by great powers during the late Qing period endures to this day as part of the CCP-sanctioned narrative of national humiliation. See Rudolf G. Wagner, “‘Dividing Up the [Chinese] Melon, Guafen 瓜分’: The Fate of a Transcultural Metaphor in the Formation of National Myth,” Journal of Transcultural Studie 8, no. 1 (2017): 9–122, https://heiup.uni- heidelberg.de/journals/index.php/transcultural/article/view/23700/17430. See also Yiqing Xu and Jiannan Zhao, “The Power of History: How a Victimization Narrative Shapes National Identity and Public Opinion in China,” Research and Politics 10, no. 2 (2023).

- An image of Hao Xiaoguang’s map is available at http://www.hxgmap.com/imag3/1309dst.jpg. See also Sun Zifa, “Hengshu kan shijie, you he da butong? Zhuanfang shu ban shijie ditu bianzhi zhe Hao Xiaoguang” [What Is the Big Difference between Looking at the World Vertically and Horizontally? An Exclusive Interview with Hao Xiaoguang, Compiler of the Vertical World Map], China News Service, April 14, 2021, https://www.chinanews.com.cn/cul/2021/04-14/9454454.shtml.