This is chapter 3 of the report “Mapping China’s Strategic Space.” To read the full report, download the PDF.

Rather than being determined by geography, a state’s geostrategy is mainly influenced by political factors. Political forces use geography to explain why and how the state thinks of directing resources, and how it exercises power. Power, or at least the self-perception of power, is the most fundamental factor that shapes a state’s mental map, observes Jakub Grygiel: “A polity endowed with geopolitical heft will naturally cast a wider look at the world, whereas a state with scarce resources will focus on its immediate neighborhood and borders. One definition of a great power is a state with interests, and the ability to influence the geopolitical dynamics, beyond its borders.”1 Great powers “broaden their geostrategic vision because of a conscious decision, not in a moment of absentmindedness.”2 There is no such thing as inadvertent empires; they are the result of “deliberate, largely self-interested choices” of decision-makers.3

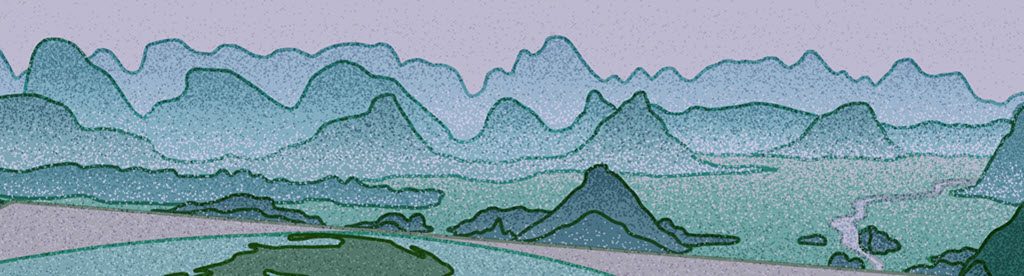

China’s broadening conceptualization of its strategic space coincides with the growth of its national power. This process has been accompanied by a sustained collective effort stretching over several decades during which political and intellectual elites have been transfixed by the concept of power. How to define it, how to quantify it, what it consists of, and how much of it China holds in comparison with other countries were all issues investigated by Chinese strategists long before their foreign counterparts began asking “whither China.” 4 Viewed from the outside, China’s assessment and acknowledgment of its national power has been a deliberate and incremental process of maturation involving academic, political, and military analysts and practitioners. Multiple interlocking discussions have occurred since the end of the Cold War, with a visible spurt starting at the turn of the century. During the following “golden decade” (see Figure 1), the government and academic strategic community wrestled with major issues pertaining to China’s power and identity, such as the constituting elements of power, the definition of core interests, success and failures of past rising powers, and the imperative of becoming a maritime power for candidates aspiring to great-power status. The task of assessing the specifics of where China should go could only be tackled once the broader question of where China stands had been addressed. On the eve of Xi Jinping’s accession to the Chinese Communist Party’s commanding heights, the collective judgment on this deceptively simple question can be summarized as follows: China is a rising power, a composite land-sea country, which must become a maritime power. This chapter will pull apart the interwoven discussions that led to this conclusion, before examining in chapter 4 the strategic community’s response to the next logical question: What should be China’s strategic direction?

FIGURE 1 The “golden decade” of PRC research on power

Assessing China’s Power

On the question of power, People’s Liberation Army officers appear, here too, as key thought leaders breaking ground for the rest of the Chinese intellectual community. In the early 1990s, military researchers from the strategic studies department of the Academy of Military Sciences led by Senior Colonel Huang Shuofeng developed extensive index systems and equations to assess and compare the comprehensive national power (zonghe guoli) of different countries in the world, including China.5 Acknowledging that military strength is but one element determining a country’s ability to prevail in international competition, 6 Huang introduced the idea of aggregating a variety of factors, both material and immaterial, during a 1984 study session ordered by Deng Xiaoping to assess China’s future security environment up to the dawn of the 21st century.7 Deng understood the crucial importance of developing China’s material power, for both domestic and international reasons, and he heretofore made this the cornerstone of his grand strategy. Thus, in late 1992, while in Zhejiang, he enjoined his comrades to “seize the opportunity to develop ourselves and constantly improve our comprehensive national power.”8

Throughout the following decades, Chinese researchers in both academia and government continued to dedicate large portions of their time and intellectual energy to assessing China’s national power and comparing it to the world’s top great powers. Researchers under Wang Songfen’s leadership of the Chinese Academy for Social Sciences (CASS), 9 academics at Tsinghua University,10 the Comprehensive National Power research group of the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR),11 and another dedicated research group within China’s National Bureau of Statistics12 each used their own set of indicators, parameters, and calculations in order to situate China relative to other great powers.13 Their conclusions differed on the timeline for China surpassing the United States in aggregate power,14 but their evaluations converged on its overall upward trajectory and ever narrowing power gap with the world’s leading nation.15 This perception was confirmed after the turn of the century and again after China overtook Japan as the second-largest world economy in 2010.

In addition to the quantification of China’s national power, the first decade of the 21st century saw an increased collective interest in studying power in all its facets and dimensions. Jiang Zemin had announced at the 16th Party Congress held in 2002 that “the first two decades of the 21st century are a period of important strategic opportunities, which we must seize tightly, and which offers bright prospects.”16 The official recognition of China’s new status as a rising power, first expressed in late 2003 in the form of the “peaceful rise” slogan (soon dropped in favor of the blander “peaceful development” formulation), was immediately followed by a series of overlapping discussions revolving around power and its applications.17 Chinese scholars began to wrestle with the definition of China’s national “core interests” and the question of how to be more proactive in asserting and defending them.18 This discussion continued even after the leadership officially issued a list in 2009.19 During the same period, Chinese political leaders, journalists, and academics also demonstrated a keen interest in the concept of soft power, a notion that was studied in detail for several years. They eventually reached the conclusion that it was “still a weak link in the country’s pursuit of comprehensive national power.”20 Hu Jintao’s October 2007 report to the 17th Party Congress explicitly made reference to soft power and outlined the need to enhance it by promoting the virtues of Chinese culture.

In parallel with these discussions, starting around 2005, academic circles began to investigate China’s grand strategy, prompted both by the need to “conduct a comprehensive assessment of the various problems that have appeared or may appear in the process of China’s rise” and by the international discussion regarding the so-called Beijing Consensus.21 In 2006, in an effort to educate the wider Chinese public on growing international power and influence, the national television broadcast a twelve-part program on the “rise of great powers” with contributions by historians of Peking University. Whether the top leadership actively encouraged the production of the series is uncertain. Robert Eng notes that a 2003 seminar on the historical lessons for the development of a major world power, attended by members of the Chinese Communist Party Politburo, was “undeniably a catalyst” for the program, which “served the political agenda of the party leadership united in pursuing the goal of the peaceful rise of China.” The documentary indeed focused on “the institutional, technological or ideological reasons for the rise of the great powers rather than on colonial wars, violence and exploitation.”22

Taken together, the collective discussions occurring over a period spanning from the end of the Cold War to after the global financial crisis reflect an increased awareness of China’s ascending power and upward trajectory. This adjusted self-perception led another large group of thinkers to begin to examine the issue of China’s “positioning” (dingwei).23 “Positioning” China does not mean finding a spot in world geography but trying to determine the implications of its growing economic, military, and political power for its international status, identity, place, and role in the world. As Wang Jisi noticed at the time, not without amusement, “few people in the world are as enthusiastic about their country’s ‘international positioning’ as Chinese scholars and commentators.”24 In the first decade of the new century, and even more so after the global financial crisis and following China overtaking Japan as the second-largest world economy in 2010, no one seemed to have any doubt about the basic fact that China was rising. But was it a regional or world power? A developing or developed country? A status quo or revisionist power? Put simply, was China a great power? When addressing these questions, most scholars still “held an equivocal view, acknowledging both the growth and weakness of…Chinese power.”25

Many of them remained cautious and recommended that China continue to abide by Deng’s advice to “keep a low profile” for fear of provoking counter responses. Analysts of its “positioning” cautiously concluded that China was a developing, still relatively backward, regional, major, powerful player, with some global influence.26 Their assessment of China’s position on the world stage reflected the country’s imperfect transformation into a world power, still caught in its old chrysalis but already showing unquestionable signs of an ability to unfurl its wings.

The Maritime Expanse as China’s “Ultimate Frontier”

Whereas China’s position on the global geopolitical chessboard can be subject to debate and evolve over time, positioning the country geographically should be straightforward enough: it is a continental power located in the eastern part of Eurasia, with a territory only second in size to Russia’s and an 18,000-kilometer coastline, ranking fourth in the world in total length and bordered by four seas—the Bohai, Yellow, East China, and South China Seas. China claims an additional 3 million square kilometers of maritime territory, including over 6,500 coastal islands, most of which are within 100 nautical miles of the mainland.27

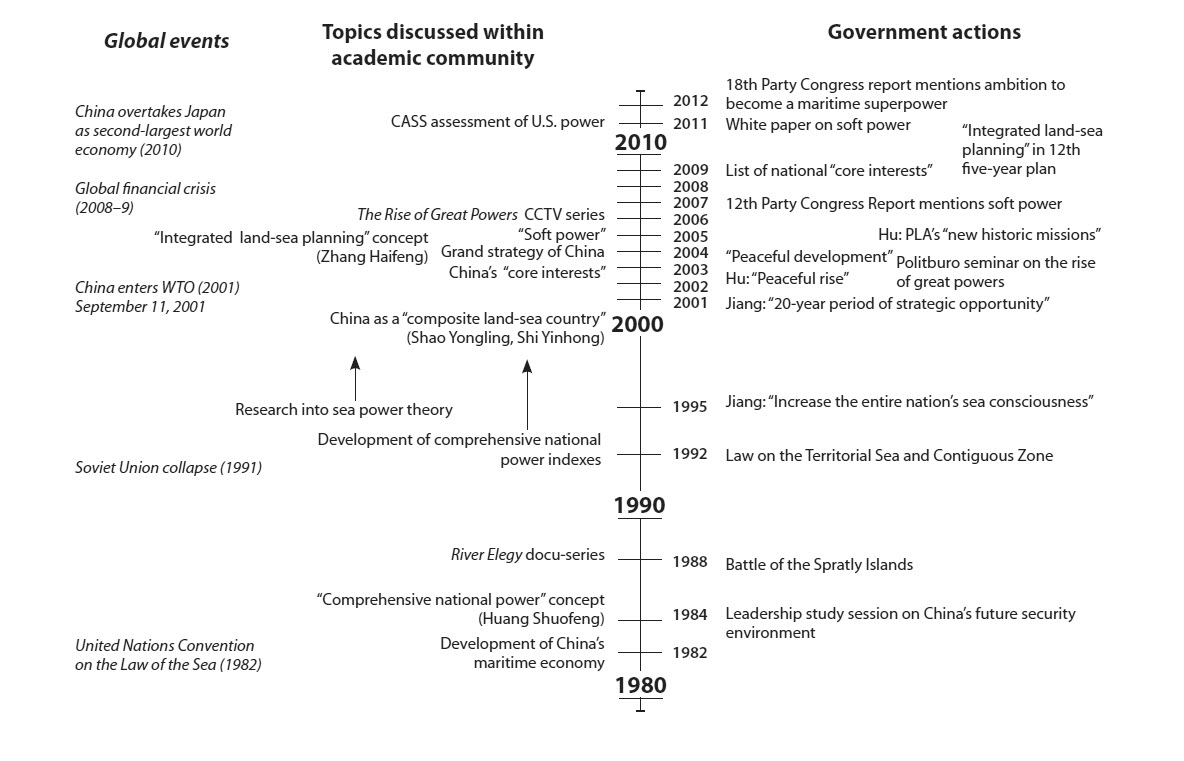

Yet geography is not necessarily destiny. For most of its history, China turned its back to the sea, and in the modern period, it did not start considering the maritime expanse more systematically as an area of geostrategic significance until the early 1980s. Extensive geophysical surveys in the Yellow and East China Seas conducted under the direction of the United Nations in the late 1960s indicating the presence of rich oil and hydrocarbon deposits had awakened Beijing’s interest in potentially exploiting marine resources. But it was the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that catalyzed Beijing’s desire to claim exclusive economic zones and continental shelves as potential additional territory over which to exert its sovereign rights. In the early 1980s, the State Oceanic Administration and CASS supported the organization of expert conferences on the development of China’s maritime economy.28 As the country began to turn to an export-led economic model, General Liu Huaqing, a military commander who led the PLA Navy from 1982 to 1988, used the expansion of China’s maritime frontiers as a justification for reallocating resources away from the land forces and to the navy. Liu oversaw the PLA Navy’s modernization and foresaw its future expansion beyond the country’s coastal waters and the so-called “island chains” constraining China’s access to the Pacific Ocean on its eastern flank (see Figure 2).29

FIGURE 2 The island chains

The oceans quickly became perceived as an “ultimate frontier” (zuihou bianjiang) for China: crucial as transportation arteries, being potential providers of food, energy, and mineral resources, and imperative for military power projection and nuclear second-strike capabilities, they were imperfectly conquered by humankind and vigorously contested by powers eager to “occupy new vital spaces,”30 including China itself. Today, China’s desire to expand its strategic space is nowhere more evident than in the maritime domain. Its incremental seaward turn sealed its positioning as a global power. As Renmin University professor of international politics Wu Zhengyu writes, the development of sea power is inextricably linked to exerting global influence, which also means that “if a country seeks to pursue a world power or world leader status, or even global hegemony, then mastering sea power may be the way to go.”31

For Andrew Rhodes, China’s budding maritime identity arrived at a crossroads in 1988, when the sea inadvertently became the symbol of two radically different visions for the future of the country:

-

A decade after the launch of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, the movement that sought democratic political reforms and a new Chinese culture was developing powerful momentum and ties to the outside world—only to meet tragic suppression a year later at Tiananmen Square. At the same time, the PLA, and the PLAN in particular, was in the midst of its own reform and new engagement on the global stage.32

Whereas the enthusiastically pro-reform TV series River Elegy (He shang) used the oceans as a representation of progress, freedom, and openness to the world, the military skirmishes over the Spratly Islands involving the PLA displayed a nationalist side that considered the oceans as a contested space that China had to secure for itself.

The conflation of geography and politics was again on full display in 1996. In the run-up to Taiwan’s first presidential election in March 1996, the PLA launched large-scale exercises that included the firing of ballistic missiles and the simulation of an amphibious assault, which were met with the deployment of two U.S. carrier battle groups to waters off Taiwan.33 The crisis injected a new dose of nationalism into domestic politics and reshaped the debate over maritime power in favor of hard-liners and the PLA Navy. Four months later, nationalist, anti-U.S., and anti-Japan sentiments flared up again as groups of “angry youths” (fenqing) and military commentators attacked the “revival of Japanese militarism” after right-wing sympathizers from the Nihon Seinensha (Japan Youth Federation) travelled to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands to renovate a lighthouse.34 Anti-Japanese demonstrators took to the streets, following in the footsteps of the late 1970s Defend Diaoyutai Movement (Baodiao, or Baowei Diaoyutai yundong) that erupted in the United States, Taiwan, and Hong Kong as “a grassroots crusade against a perceived plot by Japan and the U.S. to encroach on the Chinese territory” of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands.35 As a response, the Chinese political leadership sought to minimize the potential damage to its relations with Tokyo, as well as its own legitimacy, and “treated the issue with great care.”36 The convergence of nationalism and geography, which materialized in plain sight at that critical juncture, continues to shape the geopolitical arguments and strategic thinking occurring in China almost three decades later.

Summoning China’s “Sea Consciousness”

In addition to self-evident economic and military factors, China’s decision to turn seaward was accelerated by the collapse of the Soviet Union. With China freed from the threat that its former Soviet neighbor once posed on its northern flank, and having settled most of its land borders, China’s security environment had now “eased on land,” prompting the gradual reorientation of its strategic priorities toward the sea in search of “further development space.”37 China’s maritime surroundings provide “the way out for the continued survival and prosperity of the Chinese nation,” noted a Chinese geographer in 1992, and effectively controlling these waters “would greatly enhance our comprehensive national power and strengthen our political position in the Asia-Pacific region, and even in the world.”38 The early 1990s witnessed a “resurgence of research on sea-power theory.”39 The government introduced the Law on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone in February 1992, laying claim to the South China Sea. Academic journals and news media began publishing articles that called for China to increase its “sea consciousness,” echoing Jiang Zemin’s declaration during his 1995 inspection of a PLA Navy unit in Hainan: “Developing and using the sea will have more and more significance to China’s long-term development. We certainly need to understand the sea from a strategic highpoint, and increase the entire nation’s sea consciousness.”40 Lively internal debates about sea power ensued among strategic analysts. At the turn of the century, they were broadly divided between those who advocated for China to become a fully fledged sea power, those who backed the development of both land and sea power, and those who pushed for China to become a land power with some naval capabilities, but not a fully fledged maritime nation.41

The political leadership, recognizing both the military and economic value of the oceans, decided in favor of aggregating all these options. Hu Jintao’s 2004 call for the PLA to take on “new historic missions” redefined the Chinese navy’s operational scope beyond the coastal “near seas” and justified naval engagement in “distant seas” missions.42 That same year, Zhang Haifeng, the former director of the State Oceanic Administration’s political department and a PLA Naval Academy instructor, put forward the concept of fully integrated land and sea planning (luhai tongchou), merging the two spaces into a “single map” in support of the national economy and development.43 His idea was eventually incorporated into the government’s March 2011 12th Five-Year Plan laying out national development priorities.44 A few months later, the leadership officially expressed China’s ambition to become a “maritime superpower” (haiyang qiangguo), as enshrined in the 2012 18th Party Congress report.45

The rationales and strategic thinking behind China’s incremental transformation into a maritime power, the role of nationalism as a driver of its naval ambitions,46 and the importance of Mahanian theories in influencing China’s vision for itself as a world-class sea power,47 as well as the impact of the general evolution from a brown to a blue water mentality on the PLA Navy’s capacities, operational doctrine, and tactics, have been thoroughly studied in recent decades by U.S. naval experts, and I will not duplicate their research here.48

I will focus instead on the question of how Chinese elites made the connection between space and power, between geographic positioning and decision-making, and between China’s geopolitical identity and the contours of its expanded mental map. If, as Spykman observed, “a land power thinks in terms of continuous surfaces surrounding a central point of control, while a sea power thinks in terms of points and connecting lines dominating an immense territory,”49 then how is China (or Chinese decision-makers) “thinking in space”?50

A “Composite Land-Sea Power”

In late 2000, a PLA colonel specializing in military strategy and a prominent international relations scholar from Renmin University coauthored an article positioning China geopolitically by describing it as neither a continental nor a maritime power, but as a “composite land-sea country” (luhai fuhe guojia). That is, China has both a continental depth lacking natural obstacles and coastlines facing the open seas. The two authors, Shao Yongling and Shi Yinhong, described how this positioning had presented an “acute” double vulnerability for the PRC during the Cold War, both at sea because of the United States’ efforts to “implement a policy of blockade against China and establish a crescent-shaped military encirclement to isolate and block China” and on land because of the Soviet Union’s threat “hanging like a sword of Damocles over the Chinese people’s head.”51 Since the 1960s, the Chinese leadership relegated its maritime interests to a secondary position and focused instead on preparing for a massive Soviet military invasion coming from its northern continental border.52 The absolute priority of defeating the Soviet Union was “not only the prominent content of our political life, but also the core tasks of our economic and national defense construction, and the main spearhead of our military struggle.”53 The end of the Cold War “fundamentally changed” China’s strategic landscape: with its northern land frontiers at their most secure historically and the normalization of its relations with Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries, China was now presented with “a broad space to open up to the outside world and develop at sea.”54

Reviewing the strategic decisions made historically by countries with similar hybrid continental- maritime characteristics, such as France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain, Shao and Shi noted that whereas the “characteristics of maritime and continental nations are unchangeable, the path taken by land-sea composite countries is the result of a choice.” Successfully expanding in both directions at the same time requires “both luck and great diplomatic skill and finesse” and may end up dispersing limited resources. Hence, “China’s road to becoming a powerful country lies in getting rid of the strategic choice dilemma and double vulnerability” and in applying a principle of strategic concentration: if China wanted to expand at sea, it would have to first ensure that its continental backyard is secured. To this end, the two strategists advised strengthening relations with Russia and Central Asian countries. They concluded, rather presciently, that “under the new historical conditions, we can fully establish a new Silk Road connecting the Eurasian continent.”55 Being a composite land-sea power could be, according to some observers, the “best configuration” and an “indispensable” geopolitical feature for becoming a world power56 Yet, after carefully examining historical precedents, many Chinese strategists caution decision- makers about the various pitfalls China must avoid in its quest for greater strategic space. In two essays published in 2010 and 2012, Wu Zhengyu, a prominent geopolitical analyst specializing in sea power, warned that the transformation of composite land-sea countries into sea powers would lead to pressures coming both from neighboring countries that would react to changes in the regional balance of power and from the dominant maritime power that would perceive the growing capabilities of an emerging sea power as a marker of global ambitions meant to challenge its own hegemonic position. Regardless of the composite land-sea country’s intentions (including when they were largely defensive), both neighbors and the global hegemon would inevitably focus on the development of the rising power’s naval capacity to measure the extent of the threat, just as American scholars have done with regard to China’s rapidly increasing maritime power.57 Other experts echo Shao and Shi’s points about the two-front vulnerability of composite land-sea countries, the risk of dispersion of resources, and these countries’ difficulty in maintaining a sustainable strategic direction over the long term.58

If they try to expand simultaneously on land and at sea, composite land-sea powers may be confronted with what Jiang Peng calls “Wilhelm’s dilemma”: eliciting balancing alliances from their neighbors while misinterpreting the hegemon’s reaction—be it appeasement or hostility—as a justification for further advancing in the direction of expansion. Appeasement will be interpreted as weakness and lack of determination from the part of the hegemon to counter the rising power’s expansion, while a strong opposition will give the rising power an incentive to push harder in search of a way to “break the hegemon’s strategic encirclement.59 Jiang’s thorough study of pre–World War I Germany’s geopolitical positioning alternates between implicit and explicit parallels with the situation currently faced by the Chinese leadership.60 He notes, for example, that over the twenty years prior to the outbreak of World War I, Kaiser Wilhelm’s desk was covered with research reports on topics such as the necessity to develop a powerful navy, to build the Baghdad- Berlin railway, and to struggle for hegemony over Europe. The German emperor eventually agreed with all of them, thinking they would “bring prestige to the monarch and to the country.”61 This description makes it difficult for the reader not to transpose the scene onto Xi Jinping’s office, his desk piled high with PLA demands for a strong navy, Belt and Road infrastructure-building project proposals, and memos promoting an “Asia for Asians” ideal.

If you are a rising composite land-sea power, be a Bismarck, not a Wilhelm, advocates Jiang Peng, and choose your geopolitical positioning wisely. Instead of seeking a position as a “world power” with both land and sea capabilities, define yourself strictly as a regional continental power and “resist the temptation to pursue greater power and prestige.” Maintain a strong political decision- making center capable of coordinating and guiding the demands of various domestic interest groups. Resist those who are obsessed with “naval nationalism” and who believe that a strong navy is key to ensuring the transportation lifeline of your export-oriented economy, safeguarding national overseas interests, defending national sovereignty, and enhancing global strategic influence. Be self-restrained: Bismarck understood that there was no such thing as “absolute security” for a nation with overseas commercial interests or colonies, and that any German attempt to surpass Britain’s sea power would “trigger a futile arms race or be completely offset by the combined superiority of the British and French navies.” Jiang concludes that rising composite land-sea powers that follow Bismarck’s example will not be confronted with a “squeezing and containment” of their two geo-spaces. For China not to fall into “Wilhelm’s dilemma,” it should pursue a “regional land-power strategy of prudence, patience and moderation—not prematurely touching the sensitive geopolitical nerves of the United States, the sea power hegemon, in East Asia.”62 Jiang’s words of caution, written in 2016, may already have come too late.

China at the Center

Looking at the evolution of the discussions within China’s strategic community over the span of twenty-plus years, the consolidation of the self-perception regarding the nation’s growing power becomes gradually apparent. In addition to the sustained dedication to evaluating China’s power and comparing it to that of other nations, the focus incrementally shifted to discussing what the country should do with its increasing capabilities. This changing self-perception is not only the result of national calculations and assessments, confirmed by World Bank and International Monetary Fund projections of China’s future economic performance; it is also a product of recurrent, unsolicited external prompts. Throughout the first decade of the 21st century, foreign excitement about the supposed advent of a “Beijing Consensus,” a “G-2,” or “Chinamerica,” along with official invitations for China to become a responsible stakeholder in the existing international system, regularly validated the self-assessment of Chinese elites. Despite converging evidence of China’s future upward trajectory, further reinforced by the country overtaking Japan as the second-largest world economy in 2010, many Chinese civilian thinkers remained committed to a prudent and cautious attitude and continued to favor Deng Xiaoping’s “hide and bide” mantra. Representatives of the Chinese military, on the other hand, adopted a more nationalistic stance and vociferously supported a maximalist vision for China’s role in world affairs.63 A series of best-selling books published after 2008, all characterized by the merging of nationalist and geopolitical themes, illustrated how the domestic discussion had moved on from focusing on a lack of national self- confidence to “exploring how China can manage its transition to world leadership.”64 The books’ references to geopolitical themes such as “vital space,” the need for unchallenged access to natural resources, organismic descriptions of the state, and the struggle for survival in an unjust order harked back “to a period when international politics was based on spheres of influence,” wrote Christopher Hughes in 2011, observing with alarm the “geopolitik turn” in Chinese nationalism.65

The 2009–13 period (roughly between the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the beginning of Xi Jinping’s rule) appears to be pivotal in China’s appreciation of itself as a great power on the global stage. This was a period bookmarked by modifications of Deng’s foreign policy guideline, first by Hu Jintao in a speech to Chinese ambassadors stressing that China needed to “actively accomplish something” (jiji yousuozuowei),66 and then by Xi, who in late 2013 called for the nation to “strive for achievement” (fenfayouwei).67 Accompanying the political leadership in its journey toward greatness, prominent economists, historians, and international relations scholars from the country’s top academic institutions also recognized in November 2012 that the “hide and bide” strategy had served China well for 30 years and bought it some “time and space for development on the international stage,” but it was no longer fitting for a country that was expected to become the world’s largest economy by 2020.68

One active participant in discussions regarding China’s grand strategy was Wang Jisi, a professor at Peking University, who epitomizes the radical change that happened during this short period of time. In a paper published in 2011, Wang still advocated for China to keep a low profile and expressed fear that “some people in our country have shown a kind of empty arrogance in their exchanges with foreigners, and some research results and media reports have also appeared overly optimistic in their judgment of the international situation and China’s international positioning, which is worthy of great vigilance and should be corrected.”69 Raising China’s profile would result in losing development opportunities, damaging its relations with the United States and the West, and creating external problems that could end up affecting China domestically. To further bolster his argument, Wang quoted Mao’s speech at the 1956 commemoration of the Xinhai Revolution, warning of great powers’ excesses.70 In the English version of his essay published in Foreign Affairs, he emphasized that China’s geostrategic focus should be Asia and underlined how the Chinese leadership was “sober in its objectives” and mainly concerned with protecting national core interests “against the cluster of threats that the country faces today.”71

Two years later, any trace of this emphasis on a low profile or modest attitude had disappeared from Wang’s thinking. Instead, the renowned scholar asserted that China was standing tall at the center of the strategic chessboard and should see itself not as “the core of the old sinocentric order” (huaxia zhixu zhong de zhongyang zhi guo)—i.e., only as the dominant power in East Asia—but as a central country in the world.72 According to Wang, China is one of the three “major politico-economic plates,” together with Europe and the United States. Each possesses its “own geographical advantages and strategic depth, a large ‘vital space’ [shengcun kongjian]; each is at the center of economic cooperation areas integrated with one another under globalization.”73 China is neither a country of the global North (even though it is, by virtue of its geographic location, in the Northern Hemisphere), nor of the global South (because of its astounding economic wealth), nor of the East (because this is a Eurocentric perspective), nor, obviously, of the West. In short, China is at the center of the world.

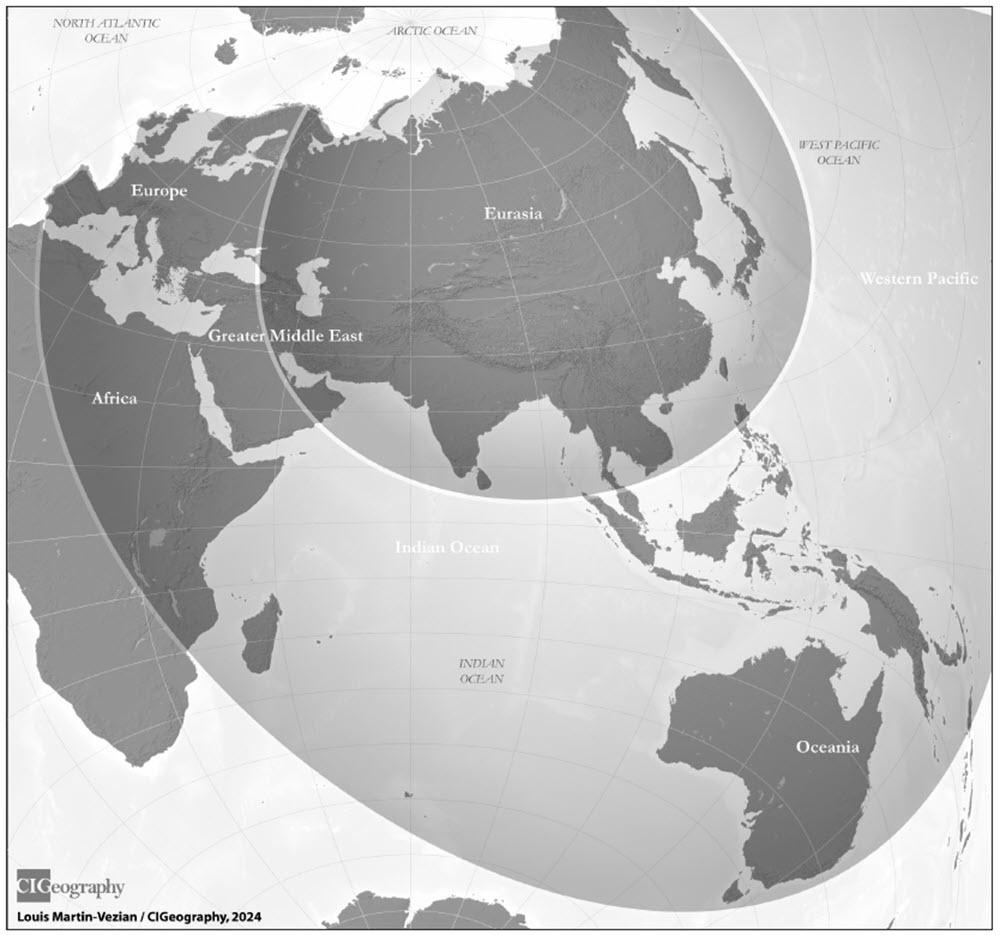

After resolving the thorny issue of China’s global positioning, Wang then called for “drawing a ‘strategic geographic picture’ that includes geopolitical, geoeconomic, geotechnological, and other factors to form a ‘grand strategy for peaceful development.’” He advocated that China should “play a bigger game in Eurasia and the world” and sketched a new mental map of China’s strategic space, extending to and including the greater Middle East, Europe, and Africa and covering both the Eurasian continent and its adjacent waters (i.e., the western Pacific and Indian Ocean) (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3 Wang Jisi’s mental map of “China at the center”

Wang envisioned a global geoeconomic strategy with the developing world as its main focus. Having pushed China’s geostrategic horizons to their widest possible extent, Wang quickly added that “at the same time” China should “maintain a sober head and a modest and prudent attitude”—a recommendation that he tones down using an excerpt from Mao Zedong’s 1935 poem “Kunlun.”74 He then concluded: “If Mao had the poetic imagination to look at the world during such a difficult period, there is all the more reason for Chinese strategists and leaders eighty years later to have the courage to keep in mind the entire world and humankind.”

Chinese strategists and leaders did, in fact, expand their strategic horizons to the entire world, as the next chapter will describe, without ever acknowledging their hegemonic intent.

Nadège Rolland is Distinguished Fellow for China Studies at the National Bureau of Asian Research. Her NBR publications include China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative (2017), “China’s Vision for a New World Order” (2020), and “A New Great Game? Situating Africa in China’s Strategic Thinking” (2021).

Read the chapters online:

Introduction: Mapping China’s Strategic Space

Chapter 2: The Return of Geopolitics

Chapter 3: “Positioning” China: Power and Identity

Chapter 4: The Logic and Grammar of Expansion

Chapter 5: Conclusion: A New Map?

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

ENDNOTES

- Jakub Grygiel, “How Land and Sea Powers Look at the Map,” National Bureau of Asian Research, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, August 23, 2023, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/how-land-and-sea-powers-look-at-the-map.

- Ibid.

- Andrew Moravcsik, review of John Darwin’s The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World System, 1830–1970, Foreign Affairs, May/June 2011.

- Robert B. Zoellick, “Whither China: From Membership to Responsibility?” (remarks to National Committee on U.S.-China Relations, New York, September 21, 2005), https://2001-2009.state.gov/s/d/former/zoellick/rem/53682.htm.

- Wu Chunqiu, “Zonghe guoli lun jiqi dui woguo fazhan zhanlüe de qidi” [On Comprehensive National Power Theory and Its Lessons for China’s Development Strategy], Guoji jishu jingji yanjiu xuebao, no. 4 (1989); Huang Shuofeng, Zonghe guoli lun [Comprehensive National Power Theory] (Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, 1992); and Da jiaoliang: Guoli qiuli lun [The Great Combat: National Power and Global Power] (Hunan: Hunan Press, 1992).

- Xu Jin and Li Wei, Gaige kaifang yilai Zhongguo duiwai zhengce bianqian yanjiu [Research on the Changes of China’s Foreign Policy since the Reform and Opening Up] (Beijing: Social Sciences Literature Press, 2017), chap. 5.

- Michael Pillsbury, China Debates the Future Security Environment (Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, 2000).

- Ni Degang, “Deng Xiaoping nanfang tanhua hou de liangci tanhua” [Deng Xiaoping’s Two Post-Southern Tour Conversations], Study Times, July 4, 2014, http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2014/0704/c69113-25238730.html.

- Wang Songfen, Shijie zhuyao guojia zonghe guoli bijiao yanjiu [Comparative Study of Comprehensive National Power of the World’s Major Countries] (Changsha: Hunan Press, 1996).

- Yan Xuetong, Yu Xiaoqiu, and Tao Jian, “Dangqian woguo waijiao mianlin de tiaozhan he renwu” [Challenges and Tasks China Faces in Current Foreign Affairs], World Economy and Politics, no. 4, 1993; Hu Angang and Men Honghua, “Zhong Mei Ri E Yin zonghe shili de guoji bijiao (1980–1998 nian)” [International Comparisons of the Comprehensive National Powers of China, the United States, Japan, Russia, and India (1980–1998)], Strategy and Management, no. 2 (2002); and Hu Angang, Zheng Yufeng, and Gao Yuning, “Dui Zhong Mei zonghe guoli de pinggu (1990–2013 nian)” [Assessment of the Comprehensive National Power of China and the United States (1990–2013)], Journal of Tsinghua University 30, no. 1 (2015).

- “Quanwei baogao cheng, Zhongguo zonghe guoli paiming shijie di qi” [Authoritative Report Says China’s Comprehensive National Power Ranks Seventh in the World], China News, September 12, 2000, https://www.chinanews.com.cn/2000-09-12/26/46039.html.

- “Li Qiang zhuchi zhaokai ‘Shijie zhuyao guojia zonghe guoli pingjia yanjiu’ keti jieti pingshen hui” [Li Qiang Presided Over the Final Review of the “Research on Evaluating the Comprehensive National Power of World Great Powers” Project], National Bureau of Statistics, November 17, 2014, http://csr.stats.gov.cn/kydt/kykx/201411/t20141117_2005.html.

- For more about Chinese academic discussions related to the Comprehensive National Power research group, see David M. Lampton, The Three Faces of Chinese Power: Might, Money, and Minds (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 20–25; and Qi Haixia, “From Comprehensive National Power to Soft Power: A Study of the Chinese Scholars’ Perception of Power,” Griffith-Tsinghua Project, “How China Sees the World,” Working Paper Series, no. 7, 2017.

- Yan Xuetong, “The Rise of China and Its Power Status,” Chinese Journal of International Politics 1, 2006. For the Chinese version, see “Zhongguo jueqi de shili diwei” [China’s Rising Power Position], Science of International Politics, no. 2 (2005).

- Hu, Zheng, and Gao, “Dui Zhong Mei zonghe guoli de pinggu (1990–2013 nian).”

- “Full Text of Jiang Zemin’s Report at the 16th Party Congress,” Xinhua, November 17, 2002. For more about Chinese perceptions of strategic opportunities and challenges, see Timothy R. Heath, “The End of China’s Period of Strategic Opportunity: Limited Opportunities, More Dangers,” NBR, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, December 19, 2023, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/the-end-of-chinas-period-of-strategic- opportunity-limited-opportunities-more-dangers.

- Robert L. Suettinger, “The Rise and Descent of ‘Peaceful Rise,’” China Leadership Monitor, Fall 2004, https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/ files/uploads/documents/clm12_rs.pdf. For an in-depth description of the “peaceful rise” concept as an influence operation orchestrated by the Ministry of State Security, see Alex Joske, Spies and Lies: How China’s Greatest Covert Operations Fooled the World (Richmond: Hardie Grant, 2022), 97–112.

- Earlier academic efforts to define China’s national interests can be traced back to Yan Xuetong, Zhongguo guojia liyi fenxi [Analysis of China’s National Interests] (Tianjin: Tianjin Publishing House, 1996); and Wang Yizhou “Guojia liyi zai sikao” [Rethinking National Interests], Chinese Social Sciences, no. 2 (2002). For overviews of the discussions, see Michael D. Swaine, “China’s Assertive Behavior—Part One: On ‘Core Interests,’” China Leadership Monitor, Winter 2011; and Jinghan Zeng, Yuefan Xiao, and Shaun Breslin, “Securing China’s Core Interests: The State of the Debate in China,” International Affairs 91, no. 2 (2015): 245–66.

- Xiao Qiang, “Dai Bingguo: The Core Interests of the People’s Republic of China,” China Digital Times, August 7, 2009, https:// chinadigitaltimes.net/2009/08/dai-bingguo-戴秉国-the-core-interests-of-the-prc. The 2011 white paper China’s Peaceful Development also issued a list of core interests as follows: “state sovereignty, national security, territorial integrity and national reunification, China’s political system established by the Constitution and overall social stability, and the basic safeguards for ensuring sustainable economic and social development.” Information Office of the State Council (PRC), China’s Peaceful Development (Beijing, September 2011), https://english.www. gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2014/09/09/content_281474986284646.htm.

- Li Mingjiang, “China Debates Soft Power,” Chinese Journal of International Politics 2, no. 2 (2008): 288; Bonnie S. Glaser and Melissa E. Murphy, “Soft Power with Chinese Characteristics: The Ongoing Debate,” in Chinese Soft Power and Its Implications for the United States: Competition and Cooperation in the Developing World, ed. Carola McGiffert (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 2009); and Osamu Sayama, “China’s Approach to Soft Power: Seeking a Balance between Nationalism, Legitimacy and International Influence,” Royal United Services Institute, RUSI Occasional Paper, March 2016. Wang Huning published the first academic paper on soft power as “Culture as National Soft Power: Soft Power,” Journal of Fudan University (1993).

- Cai Tuo, “A Brief Discussion of China’s Grand Strategy,” International Observations 2 (2006). The “Beijing Consensus” concept was put forward in 2004 by Joshua Cooper Ramo, then a professor at Tsinghua University, who contended that, bolstered by its comprehensive national power, China would now be able to open a path for other nations and challenge the Washington Consensus. See Joshua Cooper Ramo, The Beijing Consensus: Notes on the New Physics of Chinese Power (London: Foreign Policy Centre, 2004).

- Robert Y. Eng, “The Ocean as Metaphor and Avenue for Progress: Views of World History in Chinese Television Documentaries,” World History Connected 16, no. 2 (2019), https://journals.gmu.edu/index.php/whc/article/view/3736.

- Xiaoyu Pu traces the origins of the debate to a 2009 academic conference on China’s international positioning led by Cai Tuo, the director of the Global Studies Institute at China University of Political Science and Law. However, several authors, including from the PLA, had already introduced the notion in early 2006. See Xiaoyu Pu, “Controversial Identity of a Rising China,” Chinese Journal of International Politics 10, no. 2 (2017): 131–49. For earlier discussions, see Wang Haiyun, “Zhongguo muqian yi dingwei wei fuzeren fazhanzhong daguo” [It Is Currently Appropriate for China to Position Itself as a Great Responsible Developing Power], Global Times, February 24, 2006; and Wei Bin, “Zhuanxingqi Zhongguo guojia shenfen renting de kunjing” [The Dilemma of China’s National Identity during the Transition Period], Contemporary International Relations 7 (2007).

- Wang Jisi, “Zhongguo de guoji dingwei wenti yu ‘taoguangyangui, yousuozuowei’ de zhanlüe sixiang” [The Problem of China’s International Positioning and the ‘Hide and Bide’ Strategic Thought], International Studies 2 (2011).

- Wei Huang, “From Reservation to Ambiguity: Academic Debates and China’s Diplomatic Strategy under Hu’s Leadership,” East Asia 32, no. 1 (2015): 69.

- See, for example, Cai Tuo, “Dangdai Zhongguo guoji dingwei de ruogan sikao” [Some Reflections on Contemporary Chin’s International Positioning], Chinese Social Sciences 5 (2010); Zhao Kejin, “Zhongguo mianlin guoji dingwei de chongxin xuanze” [China is Facing a New Choice for International Positioning], Chinese Social Sciences 5 (2009); Cai Tuo, “Dangdai Zhongguo de dingwei yu zhanlüe linian” [Positioning and Strategic Concept of Contemporary China], Contemporary International Relations 9 (2008); Shen Guofang et al., “Zhongguo shi ge ‘daguo’ ma?” [Is China a “Great Power?”], World Knowledge 1, (2007); Wei, “Zhuanxingqi Zhongguo guojia shenfen renting de kunjing”; and Wang, “Zhongguo muqian yi dingwei wei fuzeren fazhanzhong daguo.”

- Xiao Xing, “Haiyang zai Zhongguo diyuanzhengzhi zhong de zuoyong” [The Oceans’ Role in China’s Geopolitics], Renwen dili 17, no. 1 (1992); Zhang Yaoguang, “Zhongguo de haijiang yu woguo haiyang diyuanzhengzhi zhanlüe” [China’s Maritime Frontier and National Maritime Geopolitical Strategy], Renwen dili 11, no. 2 (1996); Kong Xiaohui, “Zhongguo zuowei luhai fuhe guojia de diyuanzhanlüe xuanze” [China’s Geostrategic Choices as a Continental-Maritime Composite Country], Journal of the University of International Relations, no. 2 (2008); and Cai Anning et al., “Jiyu kongjian shijian de luhai tongchou zhanlüe sikao” [Reflections on the Land-Sea Overall Strategy from a Spatial Perspective], World Regional Studies 21, no. 1 (2012).

- Chen Wanling, “Haiyang jingjixue lilun tixi de tantao” [Discussing the Theoretical System of Maritime Economics], Maritime Economy, no. 3 (2001): 18–21, http://www.haiyangkaifayuguanli.com/ch/reader/download_pdf_file.aspx?journal_id=hykfygl&file_name=A8D77C701D0 4C881492B6AA85DE36B0C29CCBDDFFDCE02FB9F6E3A2F920389BF5E0D74DBF52B6660B1D16C0C40210D53&open_type=self&file_ no=010304.

- Andrew S. Erickson, “Geography Matters, Time Collides: Mapping China’s Maritime Strategic Space under Xi,” NBR, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, August 1, 2024, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/geography-matters-time-collides-mapping-chinas-maritime-strategic-space-under-xi/.

- Xiao, “Haiyang zai Zhongguo diyuanzhengzhi zhong de zuoyong.”

- Wu Zhengyu, “Haiquan yu luquan fuhexing qiangguo” [Sea and Land Composite Powers], World Economy and Politics, no. 2 (2012).

- Andrew Rhodes, “The 1988 Blues: Admirals, Activists, and the Development of the Chinese Maritime Identity,” Naval War College Review 74, no. 2 (2021): 67.

- Nadège Rolland, “U.S.-China Relations: A Lingering Crisis,” in China Story Yearbook: Crisis, ed. Jane Golley, Linda Jaivin, and Sharon Strange (Acton: ANU Press, 2021), 190–203, available at https://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n8254/pdf/07_chapter.pdf.

- Phil Deans, “Contending Nationalisms and the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Dispute,” Security Dialogue 31, no. 1 (2000): 119–31.

- Robert Y. Eng, “The Intractability of the Sino-Japanese Senkaku/Diaoyu Territorial Dispute: Historical Memory, People’s Diplomacy and Transnational Activism, 1961–1978,” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, November 15, 2017, https://apjjf.org/2017/22/eng.

- Deans, “Contending Nationalisms and the Diaoyutai/Senkaku Dispute.”

- Zheng Yiwei, “Luhai fuhexing Zhongguo ‘haiyang qiangguo’ zhanlüe fenxi” [Analysis of China’s “Strong Maritime Power” Strategy as a Continental-Maritime Composite Type], Haiyang wenti yanjiu (2018).

- Xiao, “Haiyang zai Zhongguo diyuanzhengzhi zhong de zuoyong.”

- Zhang Wei, “A General Review of the History of China’s Sea-Power Theory Development,” trans. Shazeda Ahmed, Naval War College Review 68, no. 4 (2015): 82. Zhang Wei’s article was originally published in July 2012 in the journal Frontiers.

- Jiang Zemin, cited in Daniel M. Hartnett and Frederic Vellucci, “Toward a Maritime Security Strategy: An Analysis of Chinese Views since the Early 1990s,” in The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles, ed. Phillip C. Saunders et al. (Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, 2011), 91; and Zhang, “A General Review of the History of China’s Sea-Power Theory Development.”

- For more details, see Hartnett and Vellucci, “Toward a Maritime Security Strategy.”

- See Bernard D. Cole, “The Evolution of China’s Naval Strategy,” interview by Nai-Yu Chen and Jeremy Rausch, NBR, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, March 26, 2024, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/the-evolution-of-chinas-naval-strategy; and Erickson, “Geography Matters, Time Collides.”

- For details about the “Integrated Land-Sea Planning,” see, among others, Xiao Peng and Song Binghua, “Luhai tongchou yanjiu zongshu” [A Review of Integrated Land-Sea Planning Research], Theoretical Horizon, no. 11 (2012); Bi Jingjing, “Lun luhai tongchou de zhanlüe shiye” [A Strategic Perspective on Integrated Land-Sea Planning] (2013); Wang Tianqing and Chen Tianyi, “Guotu kongjian guihua luhai tongchou de hexin renwu yu yingdui celüe” [The Core Objectives and Response Strategies of Land-Sea Coordination in Territorial Space Planning], Planners 39, no. 12 (2023): 8–14, http://www.planners.com.cn/uploads/20240131/ea65fc312415df4700fa80d18f073ebd.pdf.

- Xiao and Song, “Luhai tongchou yanjiu zongshu.”

- For Xi Jinping’s views on the significance of making China a maritime superpower, see “Comrade Xi Jinping’s Remarks to the Eighth Collective Study Session of the CCP Politburo,” Pacific Journal, July 30, 2013, trans. CSIS, Interpret: China, https://interpret.csis.org/ translations/comrade-xi-jinpings-remarks-to-the-eighth-collective-study-session-of-the-ccp-politburo.

- Robert S. Ross, “Nationalism, Geopolitics, and Naval Expansionism from the Nineteenth Century to the Rise of China,” Naval War College Review 71, no. 4 (2018): 11–35.

- James R. Holmes and Toshi Yoshihara, Chinese Naval Strategy in the 21st Century: The Turn to Mahan (New York: Routledge, 2008); and Toshi Yoshihara and James R. Holmes, Red Star over the Pacific: China’s Rise and the Challenge to U.S. Maritime Strategy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2010).

- The work of U.S. scholars from the Naval War College and the Center for Naval Analyses, among others, has contributed immensely to our common knowledge and understanding of the PLA Navy’s evolution and strategies.

- Nicholas J. Spykman, “Geography and Foreign Policy, II,” American Political Science Review 32, no. 2 (1938): 224.

- Andrew Rhodes, “Thinking in Space: The Role of Geography in National Security Decision-Making,” Texas National Security Review 2, no. 4 (2019): 90–108.

- Shao Yongling and Shi Yinhong, “Jindai Ouzhou luhai fuhe guojia de mingyun yu dangdai Zhongguo de xuanze” [The Fate of Modern European Composite Land–Sea Powers and Contemporary China’s Choices], Shijie jingji yu zhengzhi, no. 10 (2000).

- For a discussion of how this affected China’s mental and actual map at the time, see Covell Meyskens, “China’s Strategic Space in the Mao Era,” NBR, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, August 23, 2023 https://strategicspace.nbr.org/chinas-strategic-space-in-the-mao-era.

- Shao and Shi, “Jindai Ouzhou luhai fuhe guojia de mingyun yu dangdai Zhongguo de xuanze.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Yang Yong, “Fahui hailu jianbei youshi shi daxing hailu fuhe guojia de biran xuanze” [Giving Full Play to the Advantages of Both Land and Sea Is an Inevitable Choice for a Large Land-Sea Composite Country], Heilongjiang Social Sciences, no. 84, 2004.

- Wu, “Haiquan yu luquan fuhexing qiangguo.”

- For in-depth analysis of the concept and its implications as presented in Chinese strategic writings, see Toshi Yoshihara and Jack Bianchi, “Seizing on Weakness: Allied Strategy for Competing with China’s Globalizing Military,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2021, 37–42. See also Kong, “Zhongguo zuowei luhai fuhe guojia de diyuanzhanlüe xuanze”; Zheng, “Luhai fuhe xing Zhongguo ‘haiyang qiangguo’ zhanlüe fenxi”; Liu Yemei and Yin Zhaolu, “Bainianbianju xia Zhongguo luhai tongchou zhanlüe de lilu yu sikao” [Logic and Reflections about China’s Land-Sea Integrated Strategy in the Context of the Changes Unseen in a Century], China Development 21, no. 1 (2021); Wanyuan Peng and Lin Wang, “Historical Teachings on the Failure of the German Imperial Navy in Geopolitical Perspective,” in Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Literature, Art and Human Development (ICLAHD 2022), ed. Bootheina Majoul, Digvijay Pandya, and Lin Wang (Paris: Atlantis Press, 2023).

- Jiang Peng “Hailu fuhe xing diyuanzhengzhi daguo jueqi de ‘Weilian kunjing’ yu zhanlüe xuanze” [The “Wilhelm Dilemma” and Strategic Choices in the Rise of Maritime-Continental Composite Geopolitical Great Powers], Contemporary Asia Pacific, no. 5 (2016).

- For more historical background, see Woodruff D. Smith, “The Political Culture of Imperialism in the German Kaiserreich,” NBR, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, August 23, 2023, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/the-political-culture-of-imperialism-in-the-german-kaiserreigh.

- Jiang, “Hailu fuhe xing diyuanzhengzhi daguo jueqi de ‘Weilian kunjing’ yu zhanlüe xuanze.”

- Ibid.

- Willy Lam, “Hawks vs. Doves: Beijing Debates ‘Core Interests’ and Sino-U.S. Relations,” Jamestown Foundation, China Brief, August 19, 2010.

- Christopher Hughes, “Reclassifying Chinese Nationalism: The Geopolitik Turn,” Journal of Contemporary China 20, no. 71 (2011): 601–20. Hughes examines four books: Wolf Totem by Jiang Rong; Unhappy China by Song Xiaojun, Wang Xiaodong, Huang Jisu, Song Qiang, and Liu Yang; China’s Maritime Rights by Zhang Wenmu; and China Dream by Liu Mingfu.

- Ibid.

- For details, see Bonnie S. Glaser and Benjamin Dooley, “China’s 11th Ambassadorial Conference Signals Continuity and Change in Foreign Policy,” Jamestown Foundation, China Brief, November 4, 2009, https://jamestown.org/program/chinas-11th-ambassadorial-conferencesignals-continuity-and-change-in-foreign-policy; and M. Taylor Fravel, “Revising Deng’s Foreign Policy,” Diplomat, January 17, 2012, https://thediplomat.com/2012/01/revising-dengs-foreign-policy-2.

- Yan Xuetong, “From Keeping a Low Profile to Striving for Achievement,” Chinese Journal of International Politics 7, no. 2 (2014): 153–84.

- “Weilai shinian de Zhongguo” [China in the Coming Decade], Peking University, Report, no. R201301, March 2013.

- Wang Jisi, “Zhongguo de guoji dingwei wenti yu ‘taoguangyanghui, yousuozuowei’ de zhanlüe sixiang.”

- “[China] ought to have made a greater contribution to humanity. Her contribution over a long period has been far too small. For this we are regretful. But we must be modest—not only now, but forty-five years hence as well. We should always be modest. In our international relations, we Chinese people should get rid of great-power chauvinism resolutely, thoroughly, wholly and completely.” Translation is by Marxists.org and available at https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/works/red-book/ch18.htm.

- Wang Jisi, “China’s Search for a Grand Strategy: A Rising Great Power Finds Its Way,” Foreign Affairs, February 20, 2011.

- Wang Jisi, “Zhongguo de quanqiu dingwei yu diyuanzhengzhi zhanlüe” [China’s Global Positioning and Geostrategy], Southern Metropolis Daily, August 12, 2013, available at https://www.aisixiang.com/data/66458.html.

- Wang Jisi, “Dongxinanbei, Zhongguo ju ‘zhong’: Yi zhong zhanlüe daqiju sikao” [East, West, South, North, and China at the “Center”: A Strategic Chessboard Reflection], China’s International Strategy Review (2013). A greatly expunged version of this article was published in English in the American Interest in February 2015 under the title “China in the Middle” and is available at https://www.the-americaninterest.com/2015/02/02/china-in-the-middle.

- Translated by Xu Yuanchong, the verses Wang Jisi quotes are as follows: “Kunlun, I tell you now: You need not be so high, nor need you so much snow. Could I but lean against the sky and draw my sword to cut you into three, I would give to Europe your crest and to America your breast and leave in the Orient the rest. In a peaceful world young and old might share alike your warmth and cold!” The full poem in English, read by Lin Shaowen, can be found at https://chinaplus.cri.cn/video/culture/169/20180510/125222.html. The poem was written in October 1935, as Mao was leading the Red Army though the final stage of the Long March. Mao explained that the theme of his poem was anti-imperialism, which can be interpreted as a globalist vision and a proposition “to establish a new world order as envisaged by Mao Zedong.” See He Xin, “He Xin’s Interpretation of Mao Zedong’s Poems 2: Dominating the Universe,” Seetao, December 27, 2019, https:// www.seetao.com/details/12256.html.