This is chapter 4 of the report “Mapping China’s Strategic Space.” To read the full report, download the PDF.

The need for China to expand its “strategic space” emerged as a concept out of Chinese military circles in the mid-1980s as they attempted to sort out the strategic implications of the new paradigm devised by senior party leaders in the post-Maoist period. Following this initial effort, the formulation mostly disappeared from public discussions, only to eventually resurface around the turn of the 21st century. As their country’s ascending trajectory began to appear ineluctable, Chinese planners were carefully monitoring the trends in their strategic environment, which presented a variety of seemingly contradictory characteristics. While they were feeling increasingly confident about China’s growing comprehensive national power, they also perceived mounting external pressures and increased hostile efforts to constrain and constrict their country’s strategic space. At the same time, they determined that the United States was beginning to suffer economically, lose its moral high ground and international credibility, and overdraw its national power and was starting to reduce its global military footprint. Although this did not signal an immediate end to its hegemony, the United States would not return to its prime and was already showing “the typical characteristics of hegemonic menopause such as paranoia and distrust,” whereas China was entering its “period of adolescence.”1 If the West had failed to “strangle the New China in the cradle” when it was weak, then it would be impossible now as it was gaining unprecedented strength.2 As the United States was entering a period of relative decline, a new wave of rising powers from the developing world was emerging.3 With their rise and the “rapid power transfer from the West to the non-Western world,” the international environment was experiencing “historic changes.” 4

In the face of these rapidly changing national and international conditions, Chinese strategic thinkers engaged in lively discussions about which strategy to pursue. The exact chronology of the evolution of their ideas is difficult to establish with precision, due, first, to an abundance of overlapping discussions and, second, to the slow-burning character of the deliberations. Some concepts and ideas that initially appeared in documents between 2001 and 2005 may have been endorsed eventually by the broader strategic community or even by the political leadership only a decade later. Overall, domestic discussions follow a course that starts around the turn of the 21st century with the perception of an accelerated methodical encirclement campaign targeting China, before shifting, roughly from 2008 to 2013, toward deliberating about the directions in which to break through the perceived encirclement. During this second phase of four to five years (a period that the previous chapter found as pivotal in China’s appreciation of itself as a great power), the discussions take a radically more ambitious direction and focus on how to grant a significant expansion of China’s room for strategic maneuver. If it is to survive, develop, be able to shape the external environment, and eventually fulfill its objective to become a great power on the global stage, China needs to expand its strategic space well beyond its immediate periphery. Strategic analysts henceforth started imagining the world as China’s oyster and a future global order no longer dominated by the United States.5

As we examine the collective ruminations spanning over a long decade, it remains impossible to resolve the encirclement “chicken and egg” question. Do strategic elites feel China is encircled because they see all the constraints they face as they are about to advance outward, having already made up their mind about the necessity to expand? Is the perceived encirclement the result of China’s already active expansionism? Are the responses of other states eliciting China’s need to draw counter-encirclement plans? Regardless of whether this perception stems from genuine hostile foreign maneuvers, reflects the inherent paranoia of an authoritarian regime, or is deliberately inflated as a rationale and cover for expansionist plans, it provides the logical next step: a strategic imperative to break out of the encirclement. Thus, what began as a defensive position seamlessly transitions into offensive planning.

Parsing through the substantial number of writings produced during that period on topics related to China’s strategic space, three main observations come to mind. First, a common theme runs through these discussions: expansion is integral to China’s accession to great-power status. Some strategic thinkers may be more modest about its extent or diverge on which areas and regions should be included in China’s imagined strategic space, but the consensus is clear about the inevitability of going through an expansionist phase as part of fulfilling the nation’s destiny as a great power. Great powers have far-reaching interests and need a greater space; to paraphrase Yang Jiechi, “that’s a fact.”6 China is no exception. In that respect, the discussions that occurred a decade and a half ago were not genuine debates. Whether they belong to national security or academic circles, and whether they examine this question from a historical, geopolitical, international relations, or military perspective, Chinese thinkers are all talking about the same thing. Their main point of apparent divergence is how far and wide the outer boundaries of the country’s strategic space should go.

Second, strategic thinkers are not exclusively fixated on spatial geographies but also attach great value to nonmaterial realms. Concerns about access to natural resources, raw materials, or new markets, although sometimes presented in defense of China’s need to broaden its outlook, are usually not a central theme of their discussions.7 On the other hand, the necessity to claim an ideological safe space is particularly prominent and considered an existential matter.

Finally, it is difficult to establish a direct connection between external events and the intensification of domestic pleas to seek a greater strategic space for China. Although discussions related to perceived foreign hostile compressions and necessary strategic breakthroughs may at times be encouraged by specific events that heighten certain sensitivities, their main backdrop remains the strategic community’s determination about China’s power. As such, rather than being the proximate cause for China’s decision to expand its horizons beyond its national borders, the Obama administration’s 2011 decision to operate a strategic “rebalance” to the Asia-Pacific appears to have confirmed, rather than sparked, a collective assessment that was long foregone.

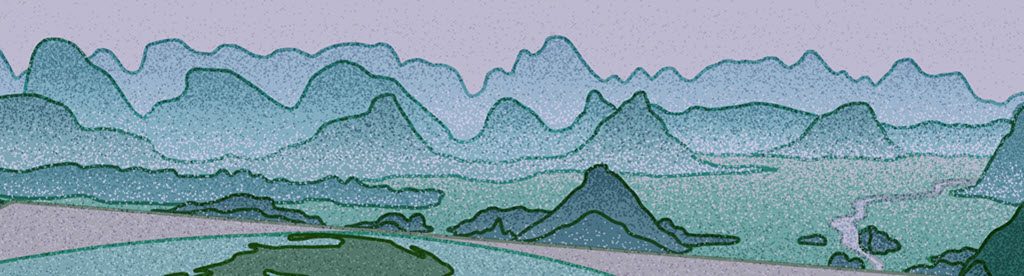

As Nadine Godehardt notes, since Xi Jinping came to power, the Chinese foreign policy discourse has included formulations that reflect the creation of a new “geopolitical code” that we need to familiarize ourselves with.8 Terms such as “vital space” and “strategic space” are prominent representatives of the evolution of a vision deeply rooted in geopolitics (see Figure 1). This chapter begins with an overview of the perception of constriction that became increasingly prevalent among Chinese strategic circles at the turn of the 21st century. The chapter then describes the various strands that together form a new grammar of expansion and delineate the contours of a new Chinese vital space.

FIGURE 1 Occurrence of the phrases “vital/survival space” (shengcun kongjian) and “strategic space” (zhanlüe kongjian) in a corpus of Chinese books in simplified characters (1979–2019)

- SOURCE: Google Books Ngram Viewer, 2024.

NOTE: “Shengcun kongjian” is used as the Chinese translation for “Lebensraum” or “living space,” a concept first introduced by Friedrich Ratzel in the 1890s which became the basic principle of Nazi Germany’s worldview and guided its military expansionism. The term is also used in Chinese texts in contexts unrelated to Nazi ideology, as a way to describe a space that grants the ability to exist or to survive, or, in other words, a space that is vital to the state’s interests. When used in such contexts, it can be understood as a conceptual equivalent to “strategic space.” Except when it is explicitly used as a translation for Lebensraum, the preferred translation for “shengcun kongjian” used in this report is “vital space” rather than “living space” as a way to convey its potential multiple meanings.

“Squeezed” Strategic Spaces

For a while, few, if any, Chinese strategic thinkers followed Senior Colonel Xu Guangyu’s effort in the late 1980s to comprehend the nature and extent of the strategic space China would need to support its rise. During subsequent years, those who used the “strategic space” formulation usually associated it with terms conveying constriction rather than extension, without much explanation as to what the concept exactly entailed and seldom with direct references to China itself. The bulk of the attention was given instead to Russia.

In the first decade of the 21st century, several articles showed an increased concern for the way Russia’s strategic space was becoming “squeezed” (jiya) as a consequence of a series of events in the post-Soviet regions. In addition to three “color revolutions” that occurred in succession in Georgia (November 2003), Ukraine (November 2004), and Kyrgyzstan (March 2005), seven of the former Warsaw Pact signatories joined NATO in March 2004, while the alliance reaffirmed its commitment to further enlargement and approved a major expansion of its role in Afghanistan.9 Chinese commentators interpreted these events as a continuation of the U.S. anti-Soviet containment policy well into the post–Cold War era. According to this interpretation, the United States was determined to prevent the re-emergence of Russia as a geostrategic competitor in Eurasia and vowed to establish a cordon sanitaire made of democracies that would inspire Russian people into following their example.10 The implicit ulterior motive was to instigate regime change in Moscow. The stationing of foreign troops in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan in the wake of the September 11 attacks was understood as an illustration of the United States’ intention to “militarily infiltrate Central Asia under the pretext of counterterrorism.” 11 Russia was seen as the victim of a deliberate Western ideological and military encirclement campaign aimed at constraining its western, southwestern, and southeastern flanks.

Evidently, Russia’s strategic space was not alone in falling prey to such maneuvers. China’s geographic proximity meant that its strategic space was also being increasingly encroached on.12 In this context, the first-ever joint military exercise between China and Russia, Peace Mission 2005, officially presented as countering terrorism, separatism, and extremism, was more fundamentally a means for the two powers to “jointly expand their strategic space” and create a strong “defense line” that the United States would be incapable of breaking.13 In addition to being the collateral victim of U.S. efforts to control the post-Soviet space and contain Russia, China was also the direct target of U.S. maneuvers. Shen Weilie, a professor of strategy at the People’s Liberation Army’s National Defense University, describes how the United States has been regarding China as its “main enemy and rival” since the founding of the People’s Republic of China and has implemented successive geostrategies spanning from overt hostility, to “Westernization, division and weakening,” to “congagement”—all aiming at encircling and containing China and posing “a serious political, economic and security threat to China.”14 Chinese analysts contend that during its second term (2004–9), the George W. Bush administration not only intensified its military, economic, and political containment of China but also ramped up its activities of “ideological infiltration.”15 The Bush Doctrine’s commitment to the global spreading of freedom and democracy was understood as the main reason for the wave of color revolutions in Eastern Europe.16 Bush’s belief that trade with China not only was good for U.S. businesses but also would help promote freedom did not go unnoticed.17 China needed to remain vigilant about the Western strategy of “peaceful evolution,” which remained unchanged, and to avoid falling “into the trap of so-called ‘democracy.’”18 Promoting the development of the Chinese private sector and strengthening ties with Chinese academics and nongovernmental organizations were therefore perceived by Chinese analysts as nothing but U.S. nonmilitary means to bring about China’s domestic political transformation.19 The survival and preservation of China’s socialist system, defined as a core national interest, continued to be threatened by the “strategy of Westernization and fragmentation by Western hostile forces.”20

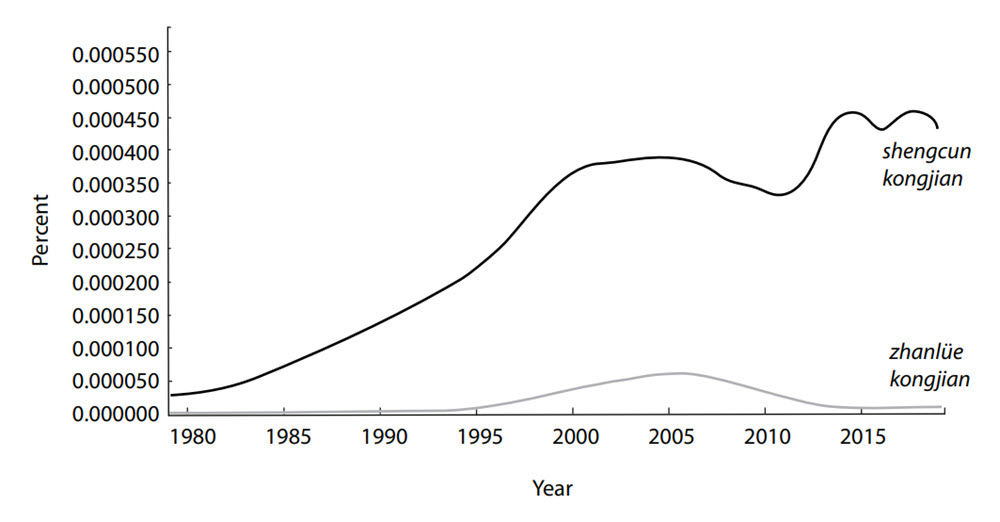

Ideological pressures were not the only threats constricting China’s strategic space. The 2001 Quadrennial Defense Review report mentioned the possibility that “a military competitor with a formidable resource base will emerge in the region [Asia]” and reaffirmed the United States’ commitment to preclude “hostile domination of critical areas, particularly Europe, Northeast Asia, the East Asian littoral, and the Middle East and Southwest Asia.”21 Although China was not mentioned by name, it was not difficult to recognize which emerging Asian power the Pentagon was getting ready to contain. Sitting in Beijing and looking at the map of U.S. military involvement, it also appeared that by 2005 the United States was concentrating two-thirds of its armed forces along an “arc” stretching through the Middle East, North Africa, and Eastern Europe, tightening the western segment of its “pincer” from Iraq and Afghanistan to Bulgaria and the Baltic Sea, while at the same time increasing the U.S. presence in East Asia, where a nascent “encircling ring” was starting to take shape with Guam as its epicenter (see Figure 2).22 It was therefore “not difficult to see that what the United States is compressing in the western section of the strategic arc is precisely China and Russia’s strategic spaces, while its maneuvers in the western Pacific are intended for the eastern section of that strategic arc.”23 The two-winged strategic pressure of NATO’s eastward expansion and the U.S. penetration into Central Asia, on the one hand, and of the strengthening of the U.S.-Japan military alliance in the Far East and the Pacific, on the other hand, posed “a serious threat to China’s security interests.”24

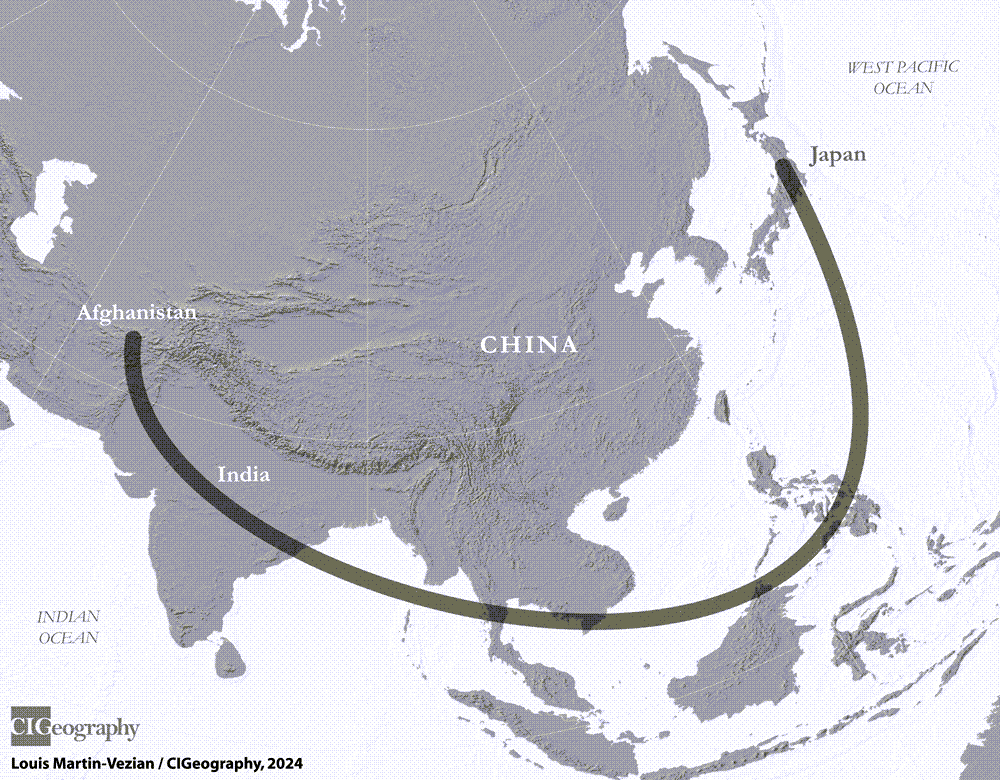

FIGURE 2 The U.S. encirclement “pincer”

Beijing’s perception of the United States’ hostile actions targeting China’s ideological, economic, and military strategic space reached another peak in 2009–11. Unrest in Tibet and Xinjiang, Barack Obama’s expressed keenness to “strengthen and sustain” U.S. leadership in the Asia-Pacific,25 a $6.4 billion U.S. arms sales package to Taiwan, the U.S. Congress urging the executive branch to designate China as a currency manipulator,26 and the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo, on top of increasing tensions in the South and East China Seas (e.g., the USNS Impeccable incident, U.S. military drills in the Yellow Sea, and flareups over the Senkaku/ Diaoyu Islands), were all seen as inauspicious manifestations of increased U.S. involvement in China’s immediate periphery.27 Evidently, scapegoating the United States as a hostile puppet master that is maneuvering to suppress China by all means necessary conveniently whitewashes the Chinese government’s own shared responsibility in triggering some of these events. For some senior PLA officers, the physical proximity of the U.S. military presence, spanning from northern Japan, to South Korea, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, India, and up to Afghanistan and Central Asia, was beginning to take the shape of an unwelcome C-shaped encirclement ring (see Figure 3)28

FIGURE 3 The C-shaped encirclement

This was reminiscent of the string of defense and security treaties the United States signed with Asian countries in the early 1950s as a barrier against Communist expansion in the region. 29 The compression of China’s strategic space was not only of a military nature, facilitated by long-range air strikes and the U.S. ability to “choke China’s lifeline at sea,” but also part of a broader strategy that included “political, economic, and ideological efforts to force China into playing the role that the United States wants.”30 The Obama administration’s decision to “pivot” or “rebalance” its military, diplomatic, and economic efforts to Asia only confirmed this analysis.

The Chinese strategic community was as displeased to see an increased U.S. presence in Eurasia in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks as it was to see the United States pack up and leave a decade later. In both cases, the U.S. decisions confirmed Chinese analysts in their predetermined conclusion: China was the main target of a deliberate U.S. encirclement campaign. After ten years of wars, which had taken a toll on U.S. resources and marred the country’s international image, combined with the disastrous aftermath of the global financial crisis, the United States was now forced to operate a “strategic contraction”31 and a “strategic readjustment.”32 It was abandoning its previous “double expansion plan” (greater Middle East and greater Central Asia) to focus instead on Asia and the western Pacific—a move the Chinese strategic community called “retreat from the west, advance eastward” (xitui dongjin)33 Now that it had pulled out of Iraq and was planning to leave Afghanistan in July 2011, the United States was set on “devoting considerable energy to dealing with China” and containing its rise in the Pacific while preserving U.S. leadership over the region.34 The United States would use every opportunity to “forestall the rise of China” and “choke” or “hinder” its development, “contain” its maritime interests, and “exploit” the conflicts with its neighbors to persuade them to join Washington’s containment scheme while strengthening the United States’ own regional alliances and dominance.35

Everything the United States was doing, either at the Eurasian continent’s western edge or on its eastern maritime flank, was an unsurprising continuation of the geostrategy it applied during the Cold War, meant to prevent any rising power from dominating Eurasia and from challenging its own hegemony. “Some people’s bodies have entered the 21st century,” wrote the People’s Daily’s Zhong Sheng in the summer of 2013, “but their head is still stuck in the past, stuck in the old era of colonial expansion, stuck in the old framework of Cold War mentality and zero-sum games.”36 In the final analysis, the so-called military “C-shaped encirclement” of China was only the “shallowest layer” of a comprehensive U.S. strategic containment that the Chinese leadership had to break through.37 Major General Peng Guangqian, deputy secretary-general of China’s National Security Forum and co-editor of the Science of Military Strategy, commented in early 2014 that the reason for U.S. efforts to “build a new strategic containment system” had everything to do with the United States’ unwillingness to recognize China’s right to prosper and to respect it as an equal capable of choosing its own path and nothing to do with China’s behavior. The senior strategic planner continued:

-

The United States is compressing China’s strategic space, which is a major challenge for China in the new era. We cannot avoid this problem, nor can we retreat from it, nor can we close our eyes and pretend not to see it. We must face it squarely. One inevitable consequence of the United States taking China as the object of its global containment is that it has accelerated China’s push into the global political arena and forced China to play on the global “great chessboard,” and to respond to the unprecedented strategic challenges facing its national security environment with a global perspective.38

In other words, China’s global expansion is justified by the necessity of leapfrogging beyond the U.S. encirclement wall. It so happened that it also is a “historic inevitability” because of China’s growing power and expanding interests.39

The Grammar of Expansion

Chinese theorists go to great lengths so as to not explicitly convey that what they have in mind is a significantly expanded Chinese realm. They unanimously resort to justifying expansion by presenting it as purely defensive and therefore not the same as Western expansionism or imperialism. Despite all their efforts to conceal it, the intent of Chinese theorists is unmistakable. True world powers, writes a PLA National Defense University professor, exercise global influence. Whereas China is still a regional power, it “inevitably” must expand its interests and influence beyond its original territory to a wider one.40 A great nation like China “cannot be confined to a narrow space forever.”41 Historical precedents show that the options for rising powers are extremely limited: either they manage to break through containment to achieve their rise, or their ambitions are “stifled in the cradle by the hegemonic power.”42 The next question geostrategists need to address, then, is in which geographic direction should China choose to realize its “strategic breakthrough” in the face of U.S. containment.43 Empire building has long lost its luster, but this is even more the case in a place and time that still bears the stigma of twentieth- century expansionism, colonialism, and territorial aggression. Instead, threats of alleged hostile encirclement schemes provide Chinese theorists with an opportune, defensive justification for extending China’s power. Another justification is the urge to defend the nation’s growing interests, which conveniently favors the upgrading of PLA power-projection capacities. However, even those who emphasize the need to break through containment divulge little about the geographies where China should go next. Where to expand when every inch of available land is under sovereign control, the principle of sovereignty is universally entrenched, and national borders are fixed?

In May 2007 a top PLA Navy officer gave the first inkling of a potential Chinese exclusive sphere of influence to the then chief of U.S. Pacific Command Admiral Timothy Keating, who recalled his counterpart as saying: “You, the U.S., take Hawaii East and we, China, will take Hawaii West and the Indian Ocean. Then you will not need to come to the western Pacific and the Indian Ocean, and we will not need to go to the eastern Pacific.”44 Perhaps this Yalta-like carving up of maritime occupation zones was what Xi Jinping had in mind when he assured Obama in 2013 that “the vast Pacific Ocean has enough space for two large countries like the United States and China.”45 But the maritime regions are not all that is included in China’s mental strategic map. In the post–global financial crisis context, Chinese discussions about spatial expansion have been congregating around themes related to strategic territories, strategic directions, and “greater” space. Not all imagined strategic spaces for China are necessarily geographic either, as will be explained in the next chapter.46 The following section presents a nonexhaustive list that is intended as an initial foray into some of the domestic deliberations related to spatial expansion.

Strategic New Frontiers/Territories

Writing about China’s strategic space in 1987, Senior Colonel Xu Guangyu identified new expanses that he believed would be subject to humankind’s further conquest, especially as the development of science and technology would enable their future exploitation. The high seas, polar regions, and outer space were natural spaces harboring “all sorts of riches.” For now, they were free of control by anyone, but powerful nations were bound to intensely compete for them. As a result of filling these empty spaces, humankind would then enter a new stage of delineating strategic frontiers.47

What U.S. sources call the “global commons” are usually described in Chinese writings as something akin to territories without a master—a terra nullius where humans have not left their mark yet, either by physical occupation or through law, or a blank slate full of promises, especially for a rising great power eager to exercise its dominion.48 Military planners in Beijing mainly see them as domains prone to power competition.49 In the words of the 2013 edition of the Science of Military Strategy, these areas are “hot spots for strategic struggles among countries.”50 Great powers have seized “early opportunities” in these strategically important spaces, making it difficult, costly, and risky for latecomers such as China to access and use them.51 Jurists, on the other hand, consider them as legal blank slates that provide China with the opportunity to become a governance rule-maker, thereby gaining a “first-mover advantage” and enhancing its “discourse power.”52 Negotiating and deciding on global standards, rules, and regulations over spaces that are still relatively unexplored and unregulated gives China an opportunity “to be involved from the beginning and even take a dominating role.”53

Reflecting the central leadership’s recognition of these spaces as crucially important, the July 2015 National Security Law included for the first time outer space, international seabed areas, and polar regions as spaces both that can be “peacefully explored and used” and where the state claims for itself the right to safeguard the security of national “activities and assets.”54 Members of the Chinese Communist Party Standing Committee who drafted the law described these spaces jointly as China’s “strategic new frontiers/territories” (zhanlüe xin jiangyu).55

In examining each of the three strategic new frontiers, Khyle Eastin, April Herlevi, and Camilla Sørensen make similar observations about how China’s efforts have incrementally moved from scientific research and exploration, motivated both by the prospect of mining critical resources and by China’s ambition to become a technological leader, to an increased interest in shaping the international rules and norms that will determine the future of how these spaces are accessed and used.56 For great powers of the past, looking at new frontiers has often translated into territorial exploration followed by military conquest and settlements. Even with rapidly advancing technological progress, it is hard to imagine a short-term future with Chinese colonies living on a 12,000 mile–deep seabed or established somewhere in outer space. For now, the use of law may be the second-best option for China to claim a form of dominion over these domains.

Strategic Directions: “Advance Westward, Resist Eastward”

The perception of encirclement elicits the imperative of breakthrough. In the early months after Xi Jinping’s accession to power, the intellectual and security community was buzzing with discussions about the strategic directions Beijing should take in order to cut through the U.S.-led comprehensive compression of China’s strategic space.57 According to Fudan University professor Qi Huaigao, the discussions converged around three main groups:

- Advocates of a maritime breakthrough pointed to the priority given by the political leadership to transforming China into a maritime power. They believed that, as a response to the “joint blockade imposed by external powers and some of our maritime neighbors,” China’s main strategic direction should be toward the South Pacific and eastern Indian Ocean in order to secure the western Pacific.

- Proponents of an “active westward advance” (jiji xijin), on the other hand, favored a continental breakthrough. They considered the economically strategic regions of South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East as crucial to broaden China’s strategic space on its western flank.

- A third group of strategic thinkers supported the idea of an “expansion of the exterior ring” (waiwei kuozhan). This is a large counter-encirclement strip including Latin America, Africa, Europe, and other relevant regions, which would outflank the U.S.-led encirclement centered on the Asia-Pacific region.58

Surveying China’s strategic environment, it became clear that each cardinal direction needed to be included, while at the same time approached differently—a situation that was soon encapsulated as “dongwen, beiqiang, xijin, nanxia”: stability in the east (managing the relationship with the United States and its Asia-Pacific allies who are collectively containing China); strengthening the north (consolidating China’s partnership with Russia); advancing westward (in Central Asia and West Asia for energy, security, and trade); and going down south (boosting cooperation with developing countries in Africa and Latin America).59

For some analysts, the scarcity of available resources demanded that China concentrate first on regions that would be least resistant to its expansion before spreading to other areas, working outward from near to far, first “from point to line,” then “from line to surface.” Africa and, albeit to a lesser degree, Latin America and Europe appeared as the best candidates at the global level. Rich in the natural resources China needed, the African continent was also located west of “the center of the 21st-century geopolitical stage, the Indian Ocean,” and east of the North Atlantic, “the psychological frontier of the Western world.” In the long term, China’s entry into the Atlantic Ocean could become key to “easing the strategic pressure from the West, and Africa could then become a potent springboard.” At the regional level, the direction of the breakthrough would be determined by the candidates’ cultural proximity and strategic alignment with China. Beijing should therefore pick Pakistan, Myanmar, Mongolia, and Kazakhstan, which would be “treated like the United States treats Mexico and Canada.”60

Proponents of a continental advance toward the west took stock of the increased pressure on China’s eastern maritime flank to propose a “rebalancing” of China’s geostrategy. A smart fighter, observes general Peng Guangqian, always dodges first when faced with an onrushing opponent. As the U.S. compression of China’s strategic space was materializing in the east, China had to sidestep and move west. The world would be “too big for the United States to cover with one hand.” China would strengthen its relations with Russia and Central Asian countries in the northwest, while in the southwest strategic direction it would develop friendly relations with South Asia, Southeast Asia, West Asia, and Africa.61 Using a similar tai chi metaphor, General Qiao Liang also describes China’s pivot to the west as a response to the U.S. compression: “I go west, neither to avoid you nor because I’m afraid of you, but to skillfully dissolve the pressure you bring to bear on me from the east.”62

Advancing westward was not a new idea, at least not for military thinkers. As early as 2001, PLA political commissar and general Liu Yazhou had asserted that it was nothing less than a “historical necessity for the Chinese nation, and it is also our destiny.”63 Liu advocated setting up trading hubs in the border regions with Central Asia, which would ultimately form a “greater Euro-Asian symbiotic economic belt,” and using economic interdependence and common interests with the countries to the west of China in order to “dismantle the U.S. encirclement” of the country.64 Liu reiterated the same point about China’s historical destiny in a short paper published in 2010, adding that “we should think of the west not as a frontier, but as the heartland of our advance.” This strategic direction followed the principle of “least resistance,” especially at a time when China’s “relations with Russia, the Central Asian states, Pakistan, and Iran are at their best in history.”65 Another article published in 2005 by a military magazine recommended breaking the U.S. containment by first focusing on China’s western flank. This maneuver would give the PLA Navy enough time to strengthen its capabilities before pivoting to the east in order to eventually break through the island chains—a scheme the author summed up as “advance westward, defend eastward” (xijin dongyu).66 Whereas Senior Colonel Dai Xu, a PLA officer well known for his nationalistic positions, pressed China to “unite with Russia and other forces, resolutely block the imminent war of the United States against Syria, and support Iran’s just position so as to keep one U.S. foot firmly stuck in the Middle East,”67 Peking University professor Wang Jisi argued that “marching westward” would widen China’s room for strategic maneuver by nurturing the potential for U.S.-China cooperation on issues such as investment, energy, terrorism, nonproliferation, and regional stability, instead of calling attention to the more confrontational stance on China’s maritime approaches.68 Increased Chinese diplomatic, economic, and trade activities with nations of South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East would develop along a three-pronged “new Silk Road” starting from China, both on land via Eurasia and at sea through the Indian Ocean.69

The idea was worth pondering. When a group of high-level academic experts from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) and top universities met in March 2013 to exchange their views on the matter, they found themselves mostly in agreement with the general idea and acknowledged that advancing westward would broaden China’s strategic space and relieve the pressure Beijing was experiencing. Some participants even pointed out that this was an inevitable choice for China on the road to become a world power. However, they diverged on two main points. First, some of these experts cautioned that openly using the term “advance” would generate misunderstandings and negative perceptions of China’s objectives. They suggested refraining from implementing this new strategy in a high-profile manner. The second point of divergence was the imagined geographic extent included in the term “west.” Whereas a representative from the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations (CICIR) suggested that the concept was not strictly geographic and included the entire developing world rather than just Central Asia and the Middle East, others delineated its boundaries up to the Persian Gulf and North Africa, and some even included the African continent.70 Wang Jisi himself supported the idea of a “further broadening of our horizons” that would be worthy of the global power rank China was now seeking.

Listing the challenges ahead, the scholars also reviewed the ways forward and suggested putting the emphasis on economic benefit and international cooperation, consolidating a “discourse system” that would prevent others from interpreting China’s actions “at will,” increasing domestic knowledge of the countries and regions west of China, and formulating a proper dedicated strategy including each subregion.71 Military strategists were enthused at the thought of increased access to the natural and energy resources of countries in Eurasia, including Russia and the Central Asian republics, as well as the Middle East and Africa. Developing economic cooperation and building transportation, energy, and power-generation infrastructure on the continent would help avoid the “interference and blockade” of maritime powers. Building railways and pipelines was only one aspect of a major historical effort to “restructure the political, economic, and geographic center of the world.”72

Greater Periphery

The October 2013 central party conference on “periphery diplomacy work” (zhoubian waijiao gongzuo) signaled an important shift in China’s foreign policy outlook. It was the first top-level meeting of its kind dedicated to the region surrounding China. The two-day session was chaired by Xi Jinping and attended by all seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee, along with representatives of key central foreign affairs party-state departments and ambassadors. It followed a series of study sessions specifically focused on China’s diplomatic and maritime strategy the Politburo held throughout that year and came on the heels of Xi’s launch of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road during his maiden trip to Southeast Asia just a few weeks earlier and the introduction of the Silk Road Economic Belt during a speech in Kazakhstan in early September. The central conference underlined with great clarity that Beijing now saw regions “around [China’s] borders” as “strategically significant” not only because of their geographic proximity, but also because of their political and economic relations with China.73 The meeting laid the groundwork for the direction that Beijing’s regional diplomacy would henceforth take.

Several foreign analysts noted the exceptional character of the gathering, but they mostly concluded that it reflected Beijing’s willingness to pursue the “good and friendly neighborhood diplomacy” (mulin youhao waijiao) that Deng Xiaoping had started implementing in the early 1990s, at a time when the country was experiencing post-Tiananmen international isolation.74 The Chinese Communist Party’s November 2002 Congress Report had already elevated China’s neighboring countries as “paramount” to its diplomatic approach, and Wen Jiabao had introduced the trilogy of mulin, anlin, fulin (harmonious/amicable, secure/tranquil, and prosperous neighbors/neighborhood environment) in an ASEAN meeting in Bali in late 2003.75 These earlier modifications of China’s official diplomatic guidelines had illustrated that instead of engaging on a bilateral basis with a select number of neighbors, Beijing had begun to consider them as an integrated whole. This approach had translated into the emergence of an “omnidirectional” peripheral diplomacy. The 2013 conference signaled a continuation of the long-held position that China needed to foster a stable external regional environment in order to maintain the course of its domestic economic and political development. Then, as before, Beijing’s objective was to reassure its neighbors about its own growing power while forestalling the creation of coalitions aimed at balancing its power.76 In addition, contrary to his predecessors and in a stark departure from Deng’s “keep a low profile” motto, Xi seemed intent on proactively shaping the regional order and asserting China’s leadership role in Asia.77

Chen Xulong, the director of the Department for International and Strategic Studies at the China Institute of International Studies, a center affiliated with the PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs, concurs with most of his foreign colleagues’ analysis. However, he also indicates that “tak[ing the] initiative in creating a favorable periphery” is not the Chinese leadership’s ultimate aim, even though it is very important for reassuring China’s neighbors in the face of its growing power and tackling the challenge posed by the U.S. rebalance, which “constitutes a disturbance to China’s strategy in Asia.” The periphery is in fact “vital for China to be a global power in a real sense” and “will serve as a springboard for China to go global and play its role of a responsible world power.”78 Stepping into the periphery is just a means toward a strategic end of China becoming a global power.

Discussion of strategic intent aside, few if any foreign analysts of Chinese politics commented on what the periphery (zhoubian) included. Most of them used the term as an equivalent to “region” or “neighborhood” (which seems to be the PRC’s preferred official English translation), referring either to the countries that share a land or maritime border with China or to Asia. Also setting aside the obvious observation that the term “periphery” inherently implies the existence of a core—hence, tacitly asserting China’s self-positioning at its center—an examination of China’s strategic space would be remiss if it did not question which countries or regions belong to the periphery.

Whereas the notion of strategic space originated from Chinese military thinkers, the conceptualization of China’s extended periphery is a brainchild of national security and intelligence circles. In 2004, at the time when domestic discussions of Russia’s “squeezed” strategic space started to emerge, and Hu Jintao was giving new historic missions to the PLA and talking about building a “harmonious world,” the World Knowledge journal published an article entitled “Interpreting China’s Greater Periphery.”79 Three of the four experts interviewed in the article worked for CICIR, a think tank affiliated with the Ministry of State Security: Lu Zhongwei, a Japan expert who became president of CICIR in 2003 and was appointed vice minister of the Ministry of State Security in 2011; Fu Mengzi, the current vice-president of CICIR, who was then director of its Institute of American Studies; and Chen Xiangyang, an analyst then working for CICIR’s Security and Strategy Institute who later became director of its World Politics Institute.80

The article makes a clear distinction between neighborhood and periphery and notes that the emergence of the concept of greater periphery reflects the evolution of China’s own development. Lu explains that the traditional understanding of what is a neighbor for China is no longer valid. Rather than being based on whether a country shares a land or maritime border with China, it should take into account whether a country shares interests with and is connected to China by security, economic, trade, energy, and cultural ties. The countries China counts as its neighbors should therefore be considered as akin to “distant relatives” (yuan qin) and be construed as “neighbors in the distance” (lin juli). From this perspective, developing countries naturally fall in that category. In a separate article published in 2005, Lu states that countries such as Mexico, Chile, Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Island states should henceforth be counted as China’s neighbors.81

Some of his colleagues at CICIR, such as Dao Shulin, Lin Limin, and Wang Zaibang, generally agreed that China’s periphery includes the Eurasian continent as well as the Pacific and Indian Ocean rims.82 According to CICIR colleague Chen Xiangyang, China’s periphery appears more geographically bounded and is divided into three levels:

- The neighborhood (i.e., countries sharing a maritime or land border with China).

- The “minor periphery” (xiao zhoubian) (i.e., the four subregions where China’s neighbors are located: Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Central Asia).

- The “greater periphery” (da zhoubian) (i.e., the regions extending outward from the minor periphery—including both the Middle East to the west, connected to Central and South Asia, and the South Pacific to the east, connected to Southeast Asia.83

To Chen, the periphery is both where China’s power, influence, and interests are located and a necessary connection toward its rise from a regional to a global power.84 Throughout the decade following this 2004 article, he regularly reiterated that these six subregions or “plates” are included in China’s “greater periphery” and urged Beijing to design a dedicated strategy to better integrate them in support of China’s leading position on the global stage.85

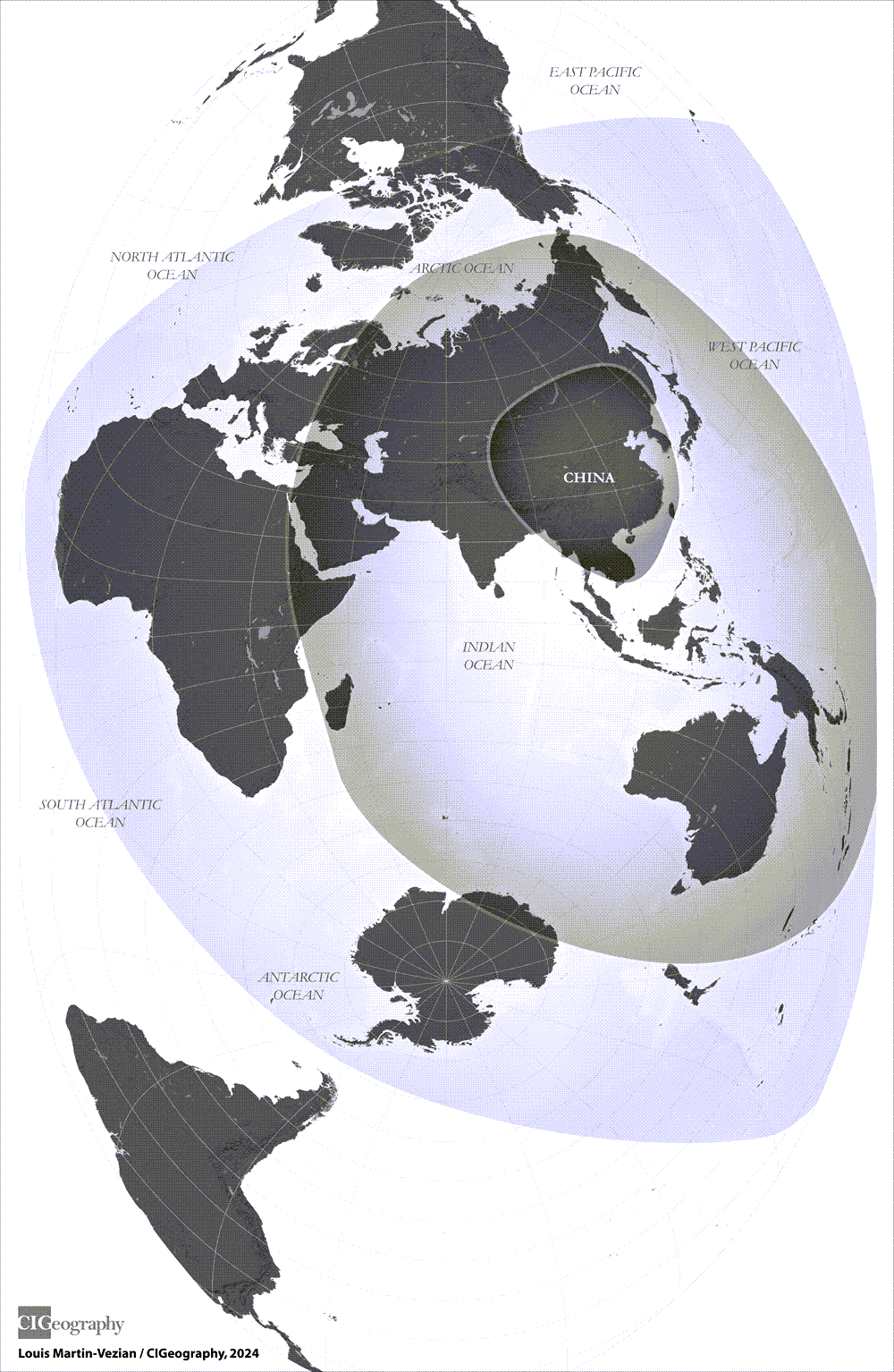

By the time that Xi chaired the central conference in 2013, the greater periphery formulation and its underlying expansionist vision had been largely adopted by political and intellectual elites connected to the political power centers.86 Rather than covering “six plates,” CICIR vice-president Yuan Peng describes the greater periphery as China’s gateway to “dash out of Asia and walk into the world,” conceived as three concentric circles with China as the core (see Figure 4):

- The “inner ring” comprises China’s fourteen land neighbors, which are of paramount importance, both for geopolitical and historical reasons.

- The “middle ring” includes China’s maritime neighbors that extend from the “inner ring” as well as the maritime area spanning from the western Pacific to the Indian Ocean to the Middle East and the parts of Central Asia and Russia that are not directly adjacent to China’s land borders.

- The “outer ring” embraces Africa, Europe, the Americas, and the polar regions.

FIGURE 4 Concentric circles of China’s strategic space

To emphasize the concentric circle structure of the greater periphery is not to “infinitely expand the connotation of China’s periphery or to equate ‘global’ with ‘peripheral,’” cautions Yuan. At the same time, the concentric circles may stretch outward depending on the speed and rhythm of China’s strategic development. Writing in late 2013, Yuan asserted that the focus of China’s periphery strategy “should still be between the inner ring and the middle ring,” which are precisely the regions of the periphery targeted by the recently launched continental “belt” and maritime “road.”87

Strategic Space Meets Belt, Road

Discussions about strategic directions and greater periphery end up delineating similar mental maps of what constitutes China’s strategic space. The overall vision is neither narrowly focused on East Asia nor fully global. It starts with the premise of a stable north (a nonadversarial Russia) and the need to break through a perceived encirclement that mostly manifests itself on China’s eastern flank. It is usually described in concentric circles with China at the core, a 360-degree perspective that includes both maritime and continental regions.

If we were to draw a Venn diagram, which spaces would be included by all groups of strategic thinkers? The result would embrace a vast continental and maritime expanse, starting with the Eurasian continent, including Southeast, South, Central, and West Asia, sometimes expanding toward and including Africa, perhaps Europe too, as well as the Eurasian continent’s adjacent waters—the South Pacific, Indian Ocean, and Arctic and Antarctic Oceans, sometimes expanding toward the Atlantic. CASS researcher Xing Guangcheng describes it as the “pan-Eurasian continent,” which refers to the Eurasian continent as well as North and East Africa, and connects the Pacific, Arctic, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans.88 Rather than as an Asian power, China’s future is described as a sort of “Eurasian power plus.” What happens beyond this already massive space is left unresolved.

When Xi Jinping announced in Kazakhstan and Indonesia China’s interest in building a Silk Road Economic Belt and a 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, which have since been branded as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), he effectively set in motion the materialization of China’s future expanded realm. The overall strategic direction toward the west was confirmed as key to provide the strategic space the country needed.89 Initially centered on the Eurasian continent and the Indian Ocean, BRI expanded to an additional outer ring after the first Belt and Road Forum in May 2017 that incorporated Africa, Latin America, the Arctic region, and the Pacific Islands.90 The 2013 and 2017 BRI maps can be interpreted as delineating the concentric circles—the core and outer perimeters—of China’s strategic space, including both the surrounding continental and maritime regions, as demands China’s self-proclaimed identity as a composite land-sea power.

Chinese analysts immediately recognized what most foreign observers still do not—that BRI is not simply an infrastructure-building program but is “of great significance to ensure our strategic security, expand our strategic space, stabilize our energy supply, ensure our economic security, and break through the strategic encirclement that contains our country.”91 It indicates the “geographic direction for China’s global strategy in the 21st century” and signifies the rejection of the idea of China as a regional power, in favor of a direct transition to the global level.92

Nadège Rolland is Distinguished Fellow for China Studies at the National Bureau of Asian Research. Her NBR publications include China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative (2017), “China’s Vision for a New World Order” (2020), and “A New Great Game? Situating Africa in China’s Strategic Thinking” (2021).

Read the chapters online:

Introduction: Mapping China’s Strategic Space

Chapter 2: The Return of Geopolitics

Chapter 3: “Positioning” China: Power and Identity

Chapter 4: The Logic and Grammar of Expansion

Chapter 5: Conclusion: A New Map?

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

ENDNOTES

- Peng Guangqian, “Sanlun zhanlüe jiyuqi—Zhongguo de zhanlüe jiyuqi tiqian zhongjiele ma?” [Three Comments on the Period of Strategic Opportunity—Has China’s Period of Strategic Opportunity Ended Prematurely?], Xinhua, March 20, 2013, http://www.xinhuanet.com/ world/2013-03/20/c_124472782.htm.

- Ibid.

- Yang Jiemian “Qianxi Aobama zhengfu de quanqiu zhanlüe tiaozheng” [An Analysis of the Obama Administration’s Global Strategic Readjustment], International Studies 2 (2011).

- Wang Honggang, “Zhong Mei ‘hezuo huoban guanxi’ xin dingwei pingxi” [Review of the New Orientation of the Sino-U.S. “Cooperative Partnership”], Contemporary International Relations 2 (2011).

- “‘Zhongguo de shijie zhixu xiangxiang yu quanqiu zhanlüe guihua’ yantao hui” [Seminar on “China’s Imagined World Order and Global Strategic Planning”], Wenhua Zongheng, February 21, 2013, http://www.21bcr.com/zhongguodeshijiezhixuxiangxiangyuquanqiuzhanlueguihuayantaohui; and Wang Xiangsui, “‘Hou Meiguo shidai’ Zhongguo de da zhanlüe” [China’s Grand Strategy in the “Post-American Era”], Observation and Exchange 139 (2014).

- At the ASEAN Regional Forum in Hanoi in 2010, the then foreign minister Yang Jiechi told his Singaporean counterpart that “China is a big country and other countries are small countries, and that’s a fact.”

- Evidently, this does not mean that energy security is not a crucial concern for China’s strategic community. For an examination of how the country seeks to solve its energy conundrum, see Gabriel Collins, “Energy as a Strategic Space for China: Words and Actions Point to a Competitive Future,” National Bureau of Asian Research, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, February 28, 2024, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/ energy-as-a-strategic-space-for-china-words-and-actions-point-to-a-competitive-future.

- Nadine Godehardt, “China’s Geopolitical Code: Shaping the Next World Order,” NBR, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, January 24, 2024, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/chinas-geopolitical-code-shaping-the-next-world-order.

- Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia joined NATO in March 2004, following the entry of Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic in 1999. The Istanbul Summit in June 2004 reaffirmed NATO’s commitment to enlargement and increased presence in Afghanistan.

- Zheng Yu, Jiang Mingjun, and Liu Fenghua, [Putin’s Eight Years: Russia’s Road to Revival (2000–2008)] (Beijing: Economic Management Publishing House, 2008), cited in Hu Ruihua, “Shixi lengzhanhou Mei-E diyuanzhengzhi kongjian jingzheng” [An Analysis of the Post-Cold War U.S.-Russia Competition for Geopolitical Space], Human Geography 25, no. 5 (2010): 111; and Yu Haibo and Chen Qiang, “Lengzhan jieshuhou Beiyue dui lianti diqu de kuozhang ji qi qianjing” [NATO’s Post–Cold War Expansion in the CIS Region and Its Prospects], Heping yu fazhan 2 (2010).

- “Zhenfengxiangdui: E jun chongxin jin zhu Zhongya diqu diyu Meiguo shentou” [Tit-for-Tat: Russian Military Re-enters Central Asia to Counter U.S. Infiltration], Sohu, October 28, 2003, http://news.sohu.com/08/79/news214907908.shtml; and Yang Huilin, “Meiguo jiajin xiang Zhongya shentou jiya Eluosi zhanlüe kongjian” [The United States Has Intensified Its Infiltration of Central Asia to Squeeze Russia’s Strategic Space], Global Times, December 1, 2004.

- Wang Wei, “Zhongguo nengfou chongpo ‘ezhi liantiao?’” [Can China Break the “Containment Chain?”], Contemporary Military Digest, September 2005; and Yu Zhengliang and Que Tianshu, “Tixi zhuanxing he Zhongguo de zhanlüe kongjian” [System Transformation and China’s Strategic Space], World Economics and Politics 10 (2006).

- “Zhong E queding shouci lianhe junyan fang’an jiang lianhe kuozhan zhanlüe kongjian” [China and Russia Confirm First Joint Military Exercises to Jointly Expand Strategic Space], China News, April 16, 2005, http://www.chinanews.com.cn/news/2005/2005-04-16/26/563586.shtml.

- Shen Weilie, “Zhongguo weilai de diyuanzhanlüe zhi sikao” [Thoughts about China’s Future Geostrategy], World Economics and Politics 9 (2001).

- Cao Changsheng, “Bushi lianren hou Meiguo ‘xihua,’ ‘fenhua’ Zhongguo de xin tedian” [New Characteristics of the U.S. “Westernization” and “Division” of China after Bush’s Reelection], in “Meiguo de ‘minzuhua’ zhanlüe zhide jingti” [U.S. “Democratization” Strategy Deserves Vigilance], Foreign Theoretical Trends 6 (2005). See also Shi Junyu, “Meiguo ezhi Zhongguo you si ce” [Four Ways the United States Contains China], Ta Kung Pao, June 24, 2005, available at http://www.aisixiang.com/data/7286.html.

- Niu Xinchun, “Meiguo de quanqiu minzuhua zhanlüe” [America’s Global Democratization Strategy], in “Meiguo de ‘minzuhua’ zhanlüe zhide jingti.

- In remarks at a Boeing plant in Washington State on May 17, 2000, Bush stated: “First, trade with China will promote freedom. Freedom is not easily contained. Once a measure of economic freedom is permitted, a measure of political freedom will follow. China today is not a free society. At home, toward its own people, it can be ruthless. Abroad, toward its neighbors, it can be reckless. When I am president, China will know that America’s values are always part of America’s agenda. Our advocacy of human freedom is not a formality of diplomacy, it is a fundamental commitment of our country. It is the source of our confidence that communism, in every form, has seen its day.” The full text is available from the Washington Post at https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/world/foreignpolicy/bushchina.html.

- Wang Guifang, “Guojia liyi yu Zhongguo anquan zhanlüe de xuanze” [National Interests and China’s Security Strategy Choices], 2006, quoted in Takashi Suzuki, “Kin’nen ni okeru Chugoku no gunji anzen hosho senmonka no senryaku ninshiki: Kokueki, chiseigaku, ‘senryaku henkyo’ o chūshin ni” [Chinese Military and Security Experts’ Recent Strategic Perceptions: Focusing on National Interests, Geopolitics, and “Strategic Frontiers”], in “Chugoku no kokunai josei to taigai seisaku” [China’s Domestic Situation and Foreign Policy], Japan Institute of International Affairs, March 2017, https://www2.jiia.or.jp/pdf/research/H28_China/H28_China_s_domestic_situation_and_foreign_policy_fulltext.pdf.

- Cao, “Bushi lianren hou Meiguo ‘xihua,’ ‘fenhua’ Zhongguo de xin tedian.”

- Ma Ping, “Guojia liyi yu junshi anquan” [National Interests and Military Security], 2005, quoted in Suzuki, “Kin’nen ni okeru Chugoku no gunji anzen hosho senmonka no senryaku ninshiki.”

- The Quadrennial Defense Review from 2001 defines the “East Asian littoral” as “the region stretching from [the] south of Japan through Australia and into the Bay of Bengal.” U.S. Department of Defense, Quadrennial Defense Review Report (Washington, D.C., September 2001), 2, 4, https://history.defense.gov/Portals/70/Documents/quadrennial/QDR2001.pdf?ver=AFts7axkH2zWUHncRd8yUg%3D%3D.

- Guo Li, “Waijun guancha: Pandian Zhongguo zhoubian de Meiguo juli bushu” [Foreign Military Watch: Taking Stock of U.S. Military Forces’ Deployment in China’s Periphery], Nanfang zhoumo, August 25, 2005.

- Ibid.

- “Zhong E queding shouci lianhe junyan fang’an jiang lianhe kuozhan zhanlüe kongjian.”

- Barack Obama, “Remarks by President Barack Obama at Suntory Hall” (Tokyo, November 14, 2009), https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/ the-press-office/remarks-president-barack-obama-suntory-hall.

- Wayne M. Morrison and Marc Labonte, “China’s Currency: An Analysis of the Economic Issues,” Congressional Research Service, CRS Report for Congress, RS21625, January 12, 2011, https://china.usc.edu/sites/default/files/article/attachments/China%20Currency%202011%20Jan.pdf.

- Xiuye Zhao, “Chinese Perception of the U.S. Strategic Position in East Asia: An Analysis of Civilian and Military Perspectives,” American Intelligence Journal 30, no. 1 (2012): 45–54.

- Dai Xu, C-xing baowei: Neiyou waihuan xia de Zhongguo tuwei [C-Shaped Encirclement: China’s Breakout of Encirclement under Internal Troubles and External Threats] (Shanghai: Wenhui Press, 2010); and “Dai Xu: Mei liyong dui Hua C xing baoweiquan buduan qiaozha xiepo Zhongguo” [Dai Xu: The United States Uses the Anti-China C-Shaped Encirclement to Blackmail and Coerce China], Global Times, March 1, 2010, available at http://mil.news.sina.com.cn/2010-03-01/1116585449.html.

- Huang Yingxu, “C baoweiquan” [C Encirclement], Window of the Northeast, June 2010.

- This quote is from an interview about the C-shaped encirclement with Ni Lexiong, a professor at Shanghai University. See “Dai Xu: Mei liyong dui Hua C xing baoweiquan buduan qiaozha xiepo Zhongguo.”

- Ma Xin and Zhang Meng, “Zhuanfang junkong yu caijun xiehui Xu Guangyu: Zhongguo yao chu luan bu jing” [Exclusive Interview with Xu Guangyu, Director of the Arms Control and Disarmament Association: China Must Deal with Chaos without Panic], Yicai, December 30, 2011, available at http://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/20111230/011211096864.shtml?from=wap.

- Yang, “Qianxi Aobama zhengfu de quanqiu zhanlüe tiaozheng.” See also “Mei zhanlüe tiaozheng, ‘xitui dongjin’ yu he wei?” [U.S. Strategic Readjustment: What Is the “Retreat from the West, Advance to the East” For?], PLA Daily, December 24, 2010, available at https://www. guancha.cn/america/2010_12_24_52579.shtml. See also Tang Yongsheng, a professor at the PLA National Defense University’s Institute of Strategic Studies, in “Shijie junshi xingshi: Junshi jingzheng shengwen ‘ruan zhanzheng’ jian tuxian” [Global Military Situation: Military Competition Heating Up and “Soft War” Becoming Increasingly Prominent], People’s Daily, December 28, 2011.

- Yang “Qianxi Aobama zhengfu de quanqiu zhanlüe tiaozheng.” See also “Mei zhanlüe tiaozheng, ‘xitui dongjin’ yu he wei?”

- Ma and Zhang, “Zhuanfang junkong yu caijun xiehui Xu Guangyu.”

- Zhao, “Chinese Perception of the U.S. Strategic Position in East Asia.”

- Zhong Sheng, “Jiya lengzhan siwei kuozhan kongjian” [Squeezing the Cold War Mentality’s Expansion Space], People’s Daily, August 14, 2013. Zhong Sheng is homophonous to “the voice of China” or “sounding the alarm bell” and is a pen name for the People’s Daily International Department, writing on important foreign affairs issues. See David Gitter and Leah Fang, “The Chinese Communist Party’s Use of Homophonous Pen Names: An Open-Source Open Secret,” Asia Policy 13, no. 1 (2018): 69–112.

- Qiao Liang, “Yinmou yi cheng yangmou, Zhongguo ruhe tuwei?” [The Plot Has Become an Open Plan. How Does China Break Through It?] (speech at the 7th China Economic Growth and Economic Security Strategy Forum, Beijing, May 29, 2012), https://www.aisixiang.com/ data/53855.html. See also “Dai Xu: Mei liyong dui Hua C xing baoweiquan buduan qiaozha xiepo Zhongguo.”

- Peng Guangqian, “Zhanlüe xichu: Yi zheng nengliang pingheng Meiguo zhanlüe dongyi de fu nengliang” [Strategic Westward: Balance the Negative Energy of the U.S. Strategic Eastward Shift with Positive Energy],Jingji daokan 3 (2014).

- Ibid.

- Zhou Bisong, Zhanlüe bianjiang: Gaodu guanzhu haiyang, taikong he wangluo kongjian anquan [Strategic Frontiers: Focusing Strongly on Maritime, Space, and Cyberspace Security] (Beijing: Long March Publishing House, 2015), cited in Suzuki, “Kin’nen ni okeru Chugoku no gunji anzen hosho senmonka no senryaku ninshiki.”

- Du Debin et al., “1990 nian yilai Zhongguo dilixue zhi diyuanzhengzhixue yanjiu jinzhan” [Progress in Geopolitics of Chinese Geographical Research since 1990], Dili yanjiu 34, no. 2 (2015).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Manny Pubby, “China Proposed Division of Pacific, Indian Ocean Regions, We Declined: U.S. Admiral,” Indian Express, May 15, 2009, https://indianexpress.com/article/news-archive/web/china-proposed-division-of-pacific-indian-ocean-regions-we-declined-us-admiral.

- “Chinese Leader Xi Jinping Joins Obama for Summit,” BBC, June 8, 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-22798572.

- Suzuki, “Kin’nen ni okeru Chugoku no gunji anzen hosho senmonka no senryaku ninshiki.”

- Xu Guangyu, “Extending Strategic Boundaries Past Geographic Borders,” JPRS-CAR-88-016, March 29, 1988, 35–38, https://apps.dtic.mil/ sti/tr/pdf/ADA348698.pdf.

- See, for example, Chen Yugang, “Zai gongyu lingyu Zhongguo bixu you ziji de zhanlüe kaolü” [China Must Have Its Own Strategic Considerations in Common Territories], World Affairs 18 (2015). For a broader discussion on how the PRC interacts with the global commons and attendant global governance regimes, see Carla P. Freeman, “An Uncommon Approach to the Global Commons: Interpreting China’s Divergent Positions on Maritime and Outer Space Governance,” China Quarterly 241 (2020).

- See, for example, Jiao Liang, “Yuzhou kongjian: Weilai guojia anquan ‘xin bianjiang’” [Outer Space: “New Frontier” of Future National Security], Xinan minbing 6 (2007); and Major General Chen Zhou, quoted in “Zhuanjia: Daguo fenfen tiaozheng junshi zhanlüe goujian xinxing weishe tixi” [Experts: Great Powers Are Adjusting Their Military Strategies and Building New Deterrence Systems], People’s Daily, December 28, 2011, available at https://www.chinanews.com.cn/gj/2011/12-28/3564397.shtml.

- Shou Xiaosong, ed., Science of Military Strategy (Beijing: Military Science Press, 2013), 74, trans. China Aerospace Studies Institute.

- Ibid.

- Zhang Zhijun and Liu Huirong, “Dangqian guoji fa kuaxueke rencai peiyang de xin renwu xin keti: Jiyu shenhai, jidi, waikong, wangluo deng ‘zhanlüe xin jiangyu’ de sikao” [New Tasks and New Topics for the Current Interdisciplinary Talent Training in International Law: Thinking about “Strategic New Territories” Such as the Deep Sea, Polar Regions, Outer Space, and the Internet], People’s Forum 3 (2021), https://aoc.ouc.edu.cn/_t719/2021/1122/c9821a357226/page.htm; and Chen, “Zai gongyu lingyu Zhongguo bixu you ziji de zhanlüe kaolü.”

- Camilla T.N. Sørensen, “The Polar Regions as New Strategic Frontiers for China,” NBR, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, January 25, 2024, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/the-polar-regions-as-new-strategic-frontiers-for-china.

- “National Security Law of the People’s Republic of China,” July 1, 2015, trans. China Law Translate, https://www.chinalawtranslate.com/ en/2015nsl.

- “Guojia anquan fa cao’an ni zengjia taikong deng xinxing lingyu de anquan weihu renwu” [National Security Law Draft to Increase Security Maintenance Tasks in New Domains Such as Space], Xinhua, June 24, 2015, available at https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2015-06/24/ content_2883509.htm.

- Khyle Eastin, “A Domain of Great Powers: The Strategic Role of Space in Achieving China’s Dream of National Rejuvenation,” NBR, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, May 10, 2024, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/a-domain-of-great-powers-the-strategic-role-of-space-in-achieving-chinas-dream-of-national-rejuvenation; April A. Herlevi, “China’s Strategic Space in the Digital Undersea,” NBR, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, March 14, 2024, https://strategicspace.nbr.org/chinas-strategic-space-in-the-digital-undersea; and Sørensen, “The Polar Regions as New Strategic Frontiers for China.”

- Peng Nian, “Zhongguo weilai zhanlüe jueze: Xijin? Nanjin?” [China’s Future Strategic Choice: Go West? Head South?], Tianda Institute, January 15, 2013.

- Qi Huaigao, “Goujian mianxiang weilai shinian de ‘da zhoubian waijiao zhanlüe’” [Building a “Greater Periphery Diplomatic Strategy” for the Upcoming Decade], World Knowledge 4 (2014).

- “Zhuanjia tan Zhongguo quanqiu zhanlüe: Ying dong wen, bei qiang, xi jin, nan xia” [Experts Discuss China’s Global Strategy: It Needs Stability in the East, Strength in the North, Advance toward the West, and Go Down South], Xinhua, December 18, 2012, https://chinanews. com.cn/mil/2012/12-18/4416116.shtml. See also Ma Xiaojun, “Zhongguo tese daguo waijiao zhanlüe lunkuo xianxian” [The Outline of a Great Power Diplomacy Strategy with Chinese Characteristics Has Emerged], Contemporary World, February 2015.

- Du Debin and Ma Yahua, “Zhongguo jueqi de guoji diyuanzhanlüe yanjiu” [International Geostrategic Research on the Rise of China], World Regional Studies 21, no. 1 (2012).

- Peng, “Zhanlüe xichu: Yi zheng nengliang pingheng Meiguo zhanlüe dongyi de fu nengliang.”

- “Mei dong yi wo xi jin: Zhong Mei boyi zhi Zhongguo zhanlüe jueze” [America Moves East While We Move West: China’s Strategic Choice in the China-U.S. Contest], Huanqiu, May 3, 2015.

- Liu Yazhou, “Da guoce” [The Grand National Strategy], 2001, https://www.aisixiang.com/data/2884.html. An English translation by Ted Wang can be found in Chinese Law and Government 40, no. 2 (2007).

- Ibid.

- Liu Yazhou, “Xi bu lun” [The Westward Theory], Phoenix Weekly, August 5, 2010.

- Wang, “Zhongguo nengfou chongpo ‘ezhi liantiao?’”

- Dai Xu, “Meiguo weidu zhixia, Zhongguo xin de zhanlüe kongjian zai nali” [Under American Containment, Where Is China’s New Strategic Space?], Aisixiang, December 20, 2012, https://www.aisixiang.com/data/60073.html.

- Wang, “Zhongguo nengfou chongpo ‘ezhi liantiao?’”

- Ibid.

- Nadège Rolland, “A New Great Game? Situating Africa in China’s Strategic Thinking,” NBR, NBR Special Report, no. 91, June 2021, https:// www.nbr.org/publication/a-new-great-game-situating-africa-in-chinas-strategic-thinking.

- Zhan Shiming, “Zhongguo de ‘xijin’ wenti: Yanpan yu sikao” [The Issue of China’s “Westward Advance”: Study and Reflections], West Asia and Africa 2 (2013).

- Wang, “‘Hou Meiguo shidai’ Zhongguo de dazhanlüe.”

- “Xi Jinping zai zhoubian waijiao gongzuo zuotan hui shang fabiao zhongyao jianghua” [Xi Jinping Delivers an Important Speech at the Conference on Periphery Diplomacy Work], Xinhua, October 25, 2013, http://www.xinhuanet.com//politics/2013-10/25/c_117878897.htm.

- For an in-depth overview of China’s diplomacy toward its neighbors during the first decade following Tiananmen, see Suisheng Zhao, “China’s Periphery Policy and Its Asian Neighbors,” Security Dialogue 30, no. 3 (1999): 335–46. See also Wang Guanghou, “Cong ‘mulin’ dao ‘mulin, anlin, fulin’: Shi xi Zhongguo zhoubian waijiao zhengce de zhuanbian” [From “Good Neighbor” to “Harmonious, Secure, and Prosperous Neighborhood”: An Analysis of the Transformation of China’s Peripheral Foreign Policy], Diplomatic Review 3 (2007); and Zhang Chi, “Historical Changes in Relations between China and Neighboring Countries (1949–2012),” Institute for Security and Development Policy, Asia Paper, March 2013.

- “Wen Jiabao zongli chuxi dongmeng shangye yu touzi fenghui bing fabiao yanjiang” [Premier Wen Jiabao Attended the ASEAN Business and Investment Summit and Delivered a Speech], Ministry of Foreign Affairs (PRC), October 8, 2003. Xi Jinping reiterated the same trilogy at the November 2014 Central Conference on Foreign Affairs Work. See “Xi Jinping chuxi zhongyang waishi gongzuo huiyi bing fabiao zhongyao jianghua” [Xi Jinping Attended the Central Conference on Foreign Affairs Work and Delivered an Important Speech], Xinhua, November 29, 2014, http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2014-11/29/c_1113457723.htm.

- Bonnie Glaser and Deep Pal, “China’s Periphery Diplomacy Initiative: Implications for China Neighbors and the United States,” China-U.S. Focus, November 7, 2013, https://www.chinausfocus.com/foreign-policy/chinas-periphery-diplomacy-initiative-implications-for-china- neighbors-and-the-united-states; Michael D. Swaine, “Chinese Views and Commentary on Periphery Diplomacy,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 28, 2014, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2014/07/chinese-views-and-commentary-on-periphery- diplomacy?lang=en; Jianwei Wang and Tiang Boon Hoo, eds., China’s Omnidirectional Peripheral Diplomacy, Series on Contemporary China 45 (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2018); and Jacob Stokes, China’s Periphery Diplomacy: Implications for Peace and Security in Asia, Special Report 467 (Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace, 2020), https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/2020-05/20200520- sr_467-chinas_periphery_diplomacy_implications_for_peace_and_security_in_asia-sr.pdf.

- Timothy Heath, “Diplomacy Work Forum: Xi Steps Up Efforts to Shape a China-Centered Regional Order,” Jamestown Foundation, China Brief, November 7, 2013, https://jamestown.org/program/diplomacy-work-forum-xi-steps-up-efforts-to-shape-a-china-centered-regional-order.

- Chen Xulong, “Xi Jinping Opens a New Era of China’s Periphery Diplomacy,” China-U.S. Focus, November 9, 2013, https://www. chinausfocus.com/foreign-policy/xin-jinping-opens-a-new-era-of-chinas-periphery-diplomacy.

- Lu Zhongwei et al., “Jiedu Zhongguo da zhoubian” [Interpreting China’s Greater Periphery], World Knowledge 24 (2004).

- The fourth expert quoted is Zhang Yunling, director of the Institute of Asia Pacific Studies at CASS and a member of the 10th, 11th, and 12th Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference national committee, a central organ of the united front work system and of its Foreign Affairs Committee.

- Lu Zhongwei, “Zhongguo ‘da zhoubian’ didai gezhong liliang fenhua zuhe taishi” [The Differentiation and Combination of Various Forces in China’s “Greater Periphery” Zone], Aisixiang, March 13, 2005, https://www.aisixiang.com/data/6070.html. Ruan Zongze, vice-president of the China Institute of International Studies, agrees with Lu Zhongwei that the greater periphery includes not only countries directly adjacent to China but also those that share interests with China. Instead of Latin America and Oceania, however, Ruan includes the European Union in China’s “peripheral extension.” See Ruan Zongze, “Suzao you liyu Zhongguo fazhan de da zhoubian huanjing” [Shaping a Greater Periphery Environment Conducive to China’s Development], Aisixiang, March 13, 2005, https://www.aisixiang.com/data/6071.html.

- “2005 nian shijie dashi qianzhan” [World Situation Outlook, 2005], Contemporary International Relations 1 (2005): 11–15.

- Lu, “Jiedu Zhongguo da zhoubian.”

- The view of the periphery both as key to China’s national interests and as a springboard for China’s rise as a global power is shared by many Chinese scholars. See, for example, Zhang Jian, “Zhongguo zhoubian waijiao zai sikao” [Rethinking China’s Periphery Diplomacy], Contemporary World 6 (2013).

- Chen Xiangyang, “Yingdui ‘da zhoubian’ liu bankuai” [Dealing with the “Greater Periphery’s” Six Plates], Liaowang, August 21, 2010; “Guanyu woguo zhoubian xingshi” [The Situation in China’s Periphery], Current Affairs Report, November 12, 2011; “Dui Zhongguo zhoubian huanjing xinbianhua de zhanlüe sikao” [Thinking Strategically about the New Changes in China’s Peripheral Environment], Yafei zongheng 1 (2012); and “Zhongguo tuijin ‘da zhoubian zhanlüe’ zhengdangshi” [Now Is the Time for China to Promote Its “Greater Periphery Strategy”], Cfisnet, January 16, 2015.

- See, for example, the October 2013 special issue of the journal published by CICIR, which invited over 20 experts and scholars from leading academic institutions across the country to tackle the question of greater periphery, “Zhoubian zhanlüe xingshi yu Zhongguo zhoubian zhanlüe” [Strategic Situation in the Periphery and China’s Periphery Strategy], Contemporary International Relations 10 (2013); Qi Huaigao and Shi Yuanhua, “Zhongguo de zhoubian anquan tiaozhan yu da zhoubian waijiao zhanlüe” [Security Challenges in China’s Periphery and Greater Periphery Diplomatic Strategy], World Economics and Politics 6 (2013); and Ling Shengli, “Zhongguo zhoubian diqu haiwai liyi weihu tantao” [Discussion on Safeguarding Overseas Interests in China’s Peripheral Regions], International Development 1 (2018): 31–50, https://www.siis.org.cn/updates/cms/old/UploadFiles/file/20180117/201801004%20%E5%87%8C%E8%83%9C%E5%88%A9.pdf.

- Yuan Peng, “Guanyu xin shiqi Zhongguo da zhoubian zhanlüe de sikao” [Reflections on China’s Periphery Strategy in the New Era], Contemporary International Relations 10 (2013).

- Xing Guangcheng, “Lijie Zhongguo xiandai sichouzhilu zhanlüe” [Understanding China’s Modern Silk Road Strategy], World Economics and Politics 12 (2014).

- Hua Yiwen, “Xi Jinping ‘liang Ya xing’ kuozhan Zhongguo zhanlüe kongjian” [Xi Jinping’s “Two Asian Trips” Broaden China’s Strategic Space], People’s Daily (international edition), September 10, 2014, http://theory.people.com.cn/n/2014/0910/c136457-25630681.html.

- The Chinese government released the “Vision for Maritime Cooperation under the Belt and Road Initiative” in June 2017, which introduced the concept of three ocean-based “blue economic passages” linking (1) China to Africa and the Mediterranean via the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, (2) China to Oceania and the South Pacific, and (3) China to Europe via the Arctic Ocean (called either the Arctic or Polar Silk Road). See “China Proposes ‘Blue Economic Passages’ for Maritime,” Xinhua, June 21, 2017, available at https://www.chinadaily. com.cn/business/2017-06/21/content_29825517.htm. For a discussion of the South Pacific as part of China’s imagined strategic space, see Peter Connolly, “China’s Quest for Strategic Space in the Pacific Islands,” NBR, Mapping China’s Strategic Space, January 16, 2024, https:// strategicspace.nbr.org/chinas-quest-for-strategic-space-in-the-pacific-islands.

- Zhao Zhouxian and Liu Guangming, “‘Yidai yilu’: Zhongguo meng yu shijie meng de jiaohui qiaoliang” [Belt and Road: A Bridge between the China Dream and the World Dream], People’s Daily, December 24, 2014, http://finance.people.com.cn/n/2014/1224/c1004-26263778.html. For more discussions about BRI as a geostrategic project, see, among others, Du Debin and Ma Yahua, “‘Yidai yilu’: Zhonghua minzu fuxing de diyuan dazhanlüe” [One Belt and One Road: The Grand Geostrategy of China’s National Rejuvenation], Geographical Research 34, no. 6 (2015); Ling Shengli “‘Yidai yilu’ zhanlüe yu zhoubian diyuan chongsu” [The “Belt and Road” Strategy and the Geopolitical Reshaping of the Periphery], International Relations Studies 1 (2016); and Li Xiao and Li Junjiu, “‘Yidai yilu’ yu Zhongguo diyuan zhengzhi jingji zhanlüe de chonggou” [“Belt and Road” and the Reshaping of China’s Geopolitical and Geoeconomic Strategies], World Economics and Politics 10 (2015).

- Du and Ma, “‘Yidai yilu’: Zhonghua minzu fuxing de diyuan dazhanlüe.”