This is chapter 2 of the report “Mapping China’s Strategic Space.” To read the full report, download the PDF.

There is an instinctive—albeit not deterministic—connection between space (in the sense of either territory or geography) and power, and numerous geographers, historians, political scientists, and philosophers have over the years attempted to uncover the laws that govern such a relationship.1 Rudolf Kjellén, the Swedish political scientist, geographer, and politician who coined the term “geopolitics,” intended to find a scientific way of analyzing the international behavior of states. He proceeded to do so by putting the emphasis on “the physical character, size and relative location of the territory of the state as central to its power position in the international system.”2 Similarly, Halford Mackinder, in his seminal 1904 lecture “The Geographical Pivot of History,” described his ambition to seek a “formula” that would “have a practical value as setting into perspective some of the competing forces in current international politics.”3 For political analysts interested in power—its accumulation, extension, and contraction—geopolitics can provide insights, or at a minimum a systematic framework useful to help think about specific strategic directions on the world map. Chinese intellectual and strategic circles preoccupied with achieving their nation’s “peaceful rise” and “great rejuvenation” in the context of enhanced great-power competition appear as ideal candidates for exploring spatial relations and their effects on great powers’ “national fortunes” and tribulations.4

For most years since the founding of the PRC, geopolitics as an academic discipline was banned in China. Nevertheless, Chinese strategists never ceased to think in geopolitical terms. At the end of the Cold War, both government experts and academics sought to assess the implications of the great-power shifts occurring in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse for their nation’s security. The explanatory power of the geopolitical discipline proved useful to understand the strategic logic of the American hegemon and draw lessons for what would come next. As China’s rise became the talk of the town in the mid-2000s, geopolitics additionally provided a convenient framework to test out geostrategies fitting China’s impending position as a great power on the world stage.

A Brief History of Geopolitics as an Academic Discipline in the PRC

Geopolitics Outlawed

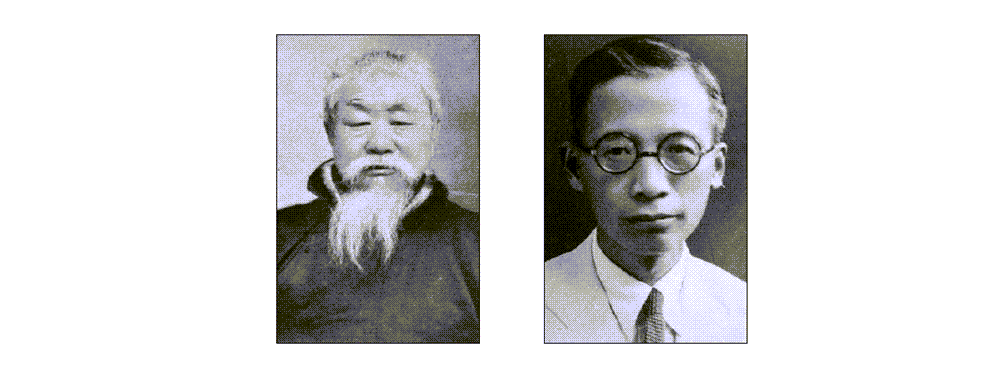

Geopolitics was prohibited as an academic discipline in the PRC until the 1990s. It had first appeared in China during the troubled times of its transition from empire to nation-state. Shellen Xiao Wu notes that the Chinese term for geopolitics (diyuanzhengzhixue) “only began circulating in the 1930s, but the underlying ideas that connect geography, natural resources, and social Darwinian competition had circulated much earlier in late Qing translations from the Japanese.”5 Issues that geopolitics purported to address resonated deeply with circles of freshly minted Chinese geographers primarily concerned with ensuring their country’s survival as an independent state at a time of great political shifts and looming existential threats.6 Geopolitics blossomed in China during the 1940s. On the eve of the Japanese invasion, works from British and German political geographers expounding the mechanics of world hegemony were translated and published as cautionary tales by Chinese intellectuals eager to “cultivate the geopolitical awareness” of their fellow citizens.7 Later on, in 1941, some of them even established an association of geopolitics (diyuanzhengzhixue xiehui) during their Chongqing exile.8 As Wu explains, Chinese intellectuals under the Japanese siege “turned to geopolitics as both an explanation for and a solution to China’s wartime dilemma. This select group of Chinese intellectuals mined German philosophy and literature for analogies to the Chinese situation” (see Figure 1).9

FIGURE 1 Zhang Xiangwen and Zhu Kezhen

SOURCE: Wikimedia.org; and Wikipedia.org.

NOTE: Zhang Xiangwen (left), one of modern China’s pioneer geographers, established the Geoscience Society of China in Tianjin in 1909. In 1934, Zhu Kezhen (right) founded the Geographical Society of China in Nanjing. The two organizations merged in 1950.

The Communist rulers of the “new China” rejected geopolitics as a theory of expansionism and a defense of imperialist aggression.10 For 40 years following the founding of the PRC, geopolitical research was therefore declared off-limits. Foreign geopolitical works remained of interest, albeit largely as objects of academic criticism.11During that period, classical writings were translated into Chinese, including Yuri Semenov’s Fascist Geopolitics in the Service of American Imperialism, Nicholas Spykman’s The Geography of Peace, Mackinder’s Democratic Ideals and Reality, John R.V. Prescott’s The Political Geography of the Oceans, and Sergey Gorshkov’s Navies in War and Peace.12

Ploughing the Geopolitical Field

The prohibition on geopolitical research was eventually lifted after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when “great changes occurred in the global political pattern and in the geo-environment in which China is located.”13 As their forefathers had done at the dawn of the twentieth century, Chinese elites turned to geopolitics to help explain the great shifts occurring in their environment and find solutions to the predicaments they posed. The Chinese government, according to Fudan professor Pan Zhongqi, had by that point recognized the importance of geopolitics and acknowledged the necessity to think about strategies in a manner more tailored to the epochal changes underway.14 The first step was to better grasp their essence. And so Chinese scholars, though initially reluctant to engage with what they considered as toxic imperialist theories, began to re-engage with the field of geopolitics.

A second wave of geopolitical revival occurred in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, as Chinese elites began to feel the tremors of yet another tectonic shift—this one caused not by the collapse of a foreign great power but by the rise of China itself. “As we all know,” noted a 2017 panel of Tsinghua University professors assessing China’s comprehensive national power, “the international financial crisis triggered by the United States has fundamentally changed the global political and economic landscape.”15 Whereas U.S. comprehensive national power had faced significant decline from 2000 to 2015, China’s had continued to increase.16 Prominent scholars proclaimed that China’s rise would end three centuries of Western global domination. Hence, it would not only change “the destiny of the Chinese people domestically” but also reshape the global allocation of strategic resources and the distribution of political power, as a consequence altering the overall future direction of humankind.17 China’s geopolitical community would need to rise to the occasion: who else would be better equipped to deal with questions about the spatial effects of changes in the global political and economic order, the implications of the emerging bipolar structure, or the strategic directions China should take to break through Western containment?18

Taking this task to heart led to an impressive spike in geopolitics-related publications in the post–Cold War period. New research centers were established, and from a handful of pioneers such as Wang Enyong, Shen Weilie, and Ye Zicheng, the cohort of Chinese scholars interested in geopolitics kept expanding. Depth improved in parallel with the quantitative leap, from the initial groundwork in the 1990s identifying the basic concepts of classical and critical geopolitics to more recent treatises dissecting the evolution of Mackinder’s thought,19 Spykman’s influence over the theory of containment,20 Carl Schmitt’s concept of Großraum,21 the development of sea power and its relevance to China’s strategic context,22 and a geostrategic interpretation of the “salt and iron” debate.23 Some works eventually made it to the top political decision-making organs of the party- state.24 (For further context, see Appendix 1 and Appendix 2.)

Chinese academics initially had to go through serious cognitive contortions to invest in a field considered as toxic both because of its association with imperialism and because of its Western lineage (“Western” and “imperialist” being sometimes used interchangeably). At the same time, these scholars recognized its usefulness as a tool for rising great powers to think about the space they need to ensure their survival, development, and ability to shape their international environment— in other words, their strategic space. These ideas were difficult to reconcile with China’s official commitment to “never seek hegemony, expansion, or sphere of influence” and to remain “a defender of world peace.” 25 It is possible that the scientific claims of geopolitics and its emphasis on material conditions comported well with the Chinese scholars’ Marxist creed or that under their internationalist veneer lay a more realist view of the nature of international relations. Whatever the case, they found a practical and patriotic purpose to their research: their work would serve national interests and strategic decision-making.26As the old bipolar world order was crumbling, as China’s integration into the world was deepening and its rise continued, and as new transportation and communication technologies were reducing the protective effects of distance, the country had to use all available tools to face upcoming strategic challenges and start to “think globally.”27

If anything, the expansion of China’s strategic mental map did not happen inadvertently. Chinese geopoliticians spent decades studying the influence of geopolitical thought on great powers’ decision-making and global geostrategies, especially the United States. They scrutinized the patterns leading to the rise and demise of great powers, the reasons motivating their expansionist appetites, the profit they gained from their hegemonic prowess, the burdens empire imposed on them, and the catastrophic consequences of overextension. They also discovered geopolitics’ practical value for the development of China’s own grand strategies. As Pan Zhongqi explains, a thorough geopolitical analysis would constitute an important “guide” for the Chinese strategic community to “identify China’s geostrategic goals, define China’s geostrategic threats, and choose China’s geostrategic means.”28

One is left to wonder about such an intense intellectual dedication, which could be interpreted as the behavior of suitors wooing the dark object of their desire. Of course, Chinese strategic elites never acknowledge they might be interested in finding tips about the best ways to achieve world domination to serve the purpose of “national rejuvenation.” By their own admission, they are more prosaically willing to learn from others’ “flaws and mistakes,”29 effectively serve China’s national development, ensure its national security, and “prevent the recurrence of historical tragedies.”30 The lessons they learned will be discussed in the following sections.

The Influence of Geopolitical Thinking on Western Powers’ Grand Strategy

Chinese geopolitical scholars are interested in understanding the concepts and mechanisms of geopolitics not only as an intellectual device to help them analyze international relations patterns but also as a factor influencing, and even guiding, major countries’ foreign strategic practice. Ge Hanwen, an associate professor at the National University of Defense Technology’s PLA School of International Relations who has led a multiyear research project on the post–Cold War influence of geopolitical thinking on a set of countries,31 finds a direct connection between the revival of geopolitics as an academic discipline in the West and the execution of key strategies, such as the U.S. rebalance to the Asia-Pacific and NATO enlargement policies.32 Hence, as one Renmin University professor writes, the “excitable minds” of Western strategists may be carried away by great-power chess games, but it still makes sense for their Chinese counterparts to “try to understand the geopolitical principles they rely on for their thinking.”33

The most prominent themes that emerge from the discussions that Chinese geopolitical scholars have conducted since the end of the Cold War are European imperialism and U.S. hegemony. The latter is usually understood as a subset or an extension of the former. There is a vast Chinese literature that studies the emergence of Western empires, examines the power transition between a declining Britain and a rising United States, and dissects the causes of the Soviet Union’s collapse. As enlightening as these publications are, they are not as relevant for our current purpose. When they observe the challenges to the survival and development of their country, Chinese strategic elites perceive the United States as the most imminent and most significant threat. The following discussion therefore focuses on describing the lessons they draw from studying the geopolitical sources of U.S. international conduct.

Scholars first acknowledge that its “superior geographical position” has bestowed on the United States “intrinsic advantages in the geopolitical game.”34 Its excellent natural and geographic endowments, combining long coastlines and a vast continental hinterland, provided the United States natural shelters from external economic and military threats in the early stages of its development as a great power and make it “stand out among the club of imperial countries such as Britain, France, and Russia.”35 But the United States’ good fortune is also its misfortune: its geographic position forces the United States to defend two oceans and to constantly expand the definition of what constitutes its strategic space. By doing so, it burdens itself with the task of providing for the security of vital sea lanes around the world and collides with other powers’ “security frontiers.”36

Second, Chinese authors ascribe U.S. international behavior and grand strategy to both cultural factors and the long-standing influence of geopolitical theoreticians.37 These two factors can be difficult to dissociate, as they appear as two sides of the same coin: the drive for hegemony is conceived as something encoded in the West’s DNA, and geopolitics is an accessory to Western imperialist aggression. Shi Yinhong believes that the United States’ evangelical culture provided a “wellspring of U.S. world hegemonic mindset” and a fertile soil that contributed to its urge to seek global dominance.38 According to Chongqing Party School analyst Fang Xu, Westerners’ fixation on spatial occupation colors not only how they understand the world but also how they interpret actions undertaken by others. Their inability to free themselves from this hegemonic lens has led some Western scholars to persist in regarding the Belt and Road Initiative “as China’s version of the Marshall Plan, a security strategy to strive for regional dominance, and accuse Chinese companies of ‘plundering resources’ and operating overseas spheres of influence in the name of BRI construction.”39

The enduring influence of classical geopolitics on such hegemonic-leaning minds should come as no surprise, given its preoccupation with nation-states’ control over geographic spaces, key nodes, and resources, and the priority given to military means in achieving these aims.40 Nicholas Spykman’s rimland theory, which introduced the idea of containment of peer competitors on the Eurasian continent through the control of its peripheral belt comprising East Asia, the Middle East, and Western Europe, has continued to “guide the spatial layout of the U.S. military and diplomatic strategy”41 and to run through successive U.S. national security strategies since the end of World War II.42 Zbigniew Brzezinski’s “grand chessboard” concept is essentially the continuation into the post–Cold War period of Spykman’s vision. He shares with Spykman a similar goal of perpetuating American hegemony43 and a persisting influence over U.S. grand strategy making.44 Yesterday’s containment of the Soviet Union and today’s Indo-Pacific strategy are identical in both their aim and means: to uphold U.S. global dominance and prevent the emergence on the Eurasian continent of any state or political and economic alliance that may compete with the United States.45

With the development of science and technology, the traditional focus of geopolitics on space as a three-dimensional physical realm (land, sea, air) has expanded to include a “virtual space” whose contours are delineated by economic, cultural, and informational factors, thereby broadening the scope of issues national security strategies need to address.46 Classical geopolitics, with its emphasis on territorial expansion and the dichotomy between continental and maritime powers, has increasingly proved unconvincing, especially at a time of globalization-induced interdependence.47 As a consequence, the formulation and implementation of U.S. national security strategies since the end of the Cold War have been increasingly heavily influenced by the introduction of cultural and civilizational elements into the geopolitical field, as epitomized by Samuel Huntington’s 1996 book The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Geographic blocs and alliances based on Cold War ideology are giving way to coalitions based on cultural identity, and “the fault lines between civilizations are becoming the central dividing lines of global political conflicts.”48

Formulating Geopolitics “with Chinese Characteristics”

Having studied in detail the evolution of geopolitics since its emergence as a discipline and having established its value in understanding the foundation of past and current U.S. grand strategies, some Chinese scholars then proceeded, around a decade ago, to examine China’s own tradition of geopolitical thought and its applicability to the making of a grand strategy fitting China’s contemporary characteristics and requirements.

Those who chose to revert to China’s pre-modern history to track homegrown geopolitical concepts had to face a few paradoxes. The immediate challenge was the need to overcome a peculiar form of historical revisionism: how could geopolitics be found in China centuries before it was even invented? In addition, ancient China was little concerned about conceptualizing the world outside the central plains where the huaxia culture was nested, beyond calling it indiscriminately the “barbarian” realm (yi).49 Its conception of the world was that China was the world and encompassed “everything under heaven” (tianxia). Liu Yungang and Wang Fenglong acknowledge the limitations of an exercise that would try to “blindly transplant” spatial conceptions of the Han, Tang, Song, and Ming dynasties into the contemporary context.50 At the same time, they attempt to identify Chinese equivalents of geopolitical concepts and find evidence of a rich geostrategic tradition. They discern parallels between the balance-of-power system in nineteenth-century Europe and China’s Spring and Autumn (770–475 BCE) and Warring States (475–221 BCE) periods. Both were periods of intense competition for power between rival states, characterized by military and diplomatic maneuvering and the emergence of major military- strategic configurations such as “vertical alliances, horizontal coalitions” (hezong lianheng).51 Zheng Yongnian, former director of the East Asian Institute at the National University of Singapore, identified the issue of borderlands as key in traditional Chinese geopolitics, which translated, according to Zheng, into a preference for passive defense rather than expansionism, for continental rather than maritime power, and for a focus on regional periphery rather than a global outlook. Zheng portrayed the tributary system as “the manifestation of China’s geopolitics,” with its main goal being the stabilization of the periphery.52

Other scholars associate the “birth of China’s geopolitical consciousness” with Mao Zedong.53 Liu Xiaofeng dates it back to Mao’s August 1946 mention of the existence of a vast zone separating the United States and the Soviet Union,54 which Liu claims, without further explanation other than “Mao’s superior geopolitical wisdom,” is the “exact opposite” of Spykman’s rimland theory.55 Without judging whether his thought is “superior” or not, Mao does have a special place in Chinese modern geopolitics. As early as 1938, when China was in the throes of war against Japan and Chinese forces were “strategically encircled” by the enemy, the Communist Party leader was able to see beyond the immediate military battlefield and to apprehend the broader international politics at play on a global chessboard:

- If the game of weiqi is extended to include the world, there is yet a third form of encirclement as between us and the enemy, namely, the interrelation between the front of aggression and the front of peace. The enemy encircles China, the Soviet Union, France and Czechoslovakia with his front of aggression, while we counter-encircle Germany, Japan and Italy with our front of peace.56

The “front of peace” gathering all anti-fascist “strategic units” would eventually form “a gigantic net” from which Japanese imperialism would not escape alive. In other words, Mao envisioned a global counter-encirclement strategy that ended up looking like a containment strategy.

Encirclement and counter-encirclement, interior and exterior lines, efforts to contain the expansion of imperialist powers, and other geopolitical configurations remained important themes in Mao’s strategic thinking long after the war against imperial Japan had ended. In a February 1973 meeting with Henry Kissinger and Winston Lord in Zhongnanhai, Mao mentioned the need to “draw a horizontal line” through the United States, Japan, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, and Europe that would play a restraining role on the expansion of Soviet imperialism (see Figure 2).57 Peking University professor Wang Jisi describes this “one line” (yi tiao xian) as China’s first geostrategic concept in the modern era, a concept that supplanted the prevailing Cold War bipolar division of the world into Eastern and Western camps because it envisioned the temporary alignment of China, technically a power of the “East,” with a major Western power in order to defeat the Soviet Union (back then, considered as the primary threat to China’s survival).58

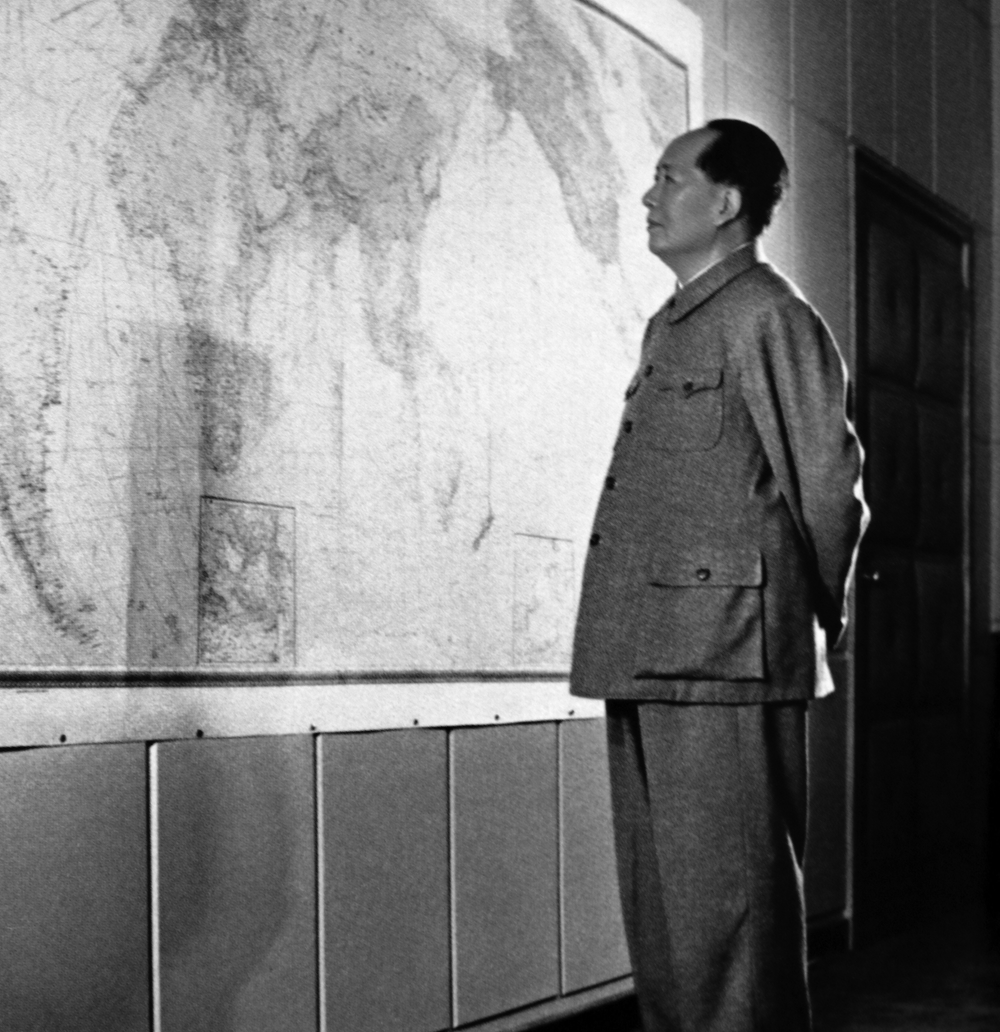

FIGURE 2 Mao’s “one horizontal line, one vast area”

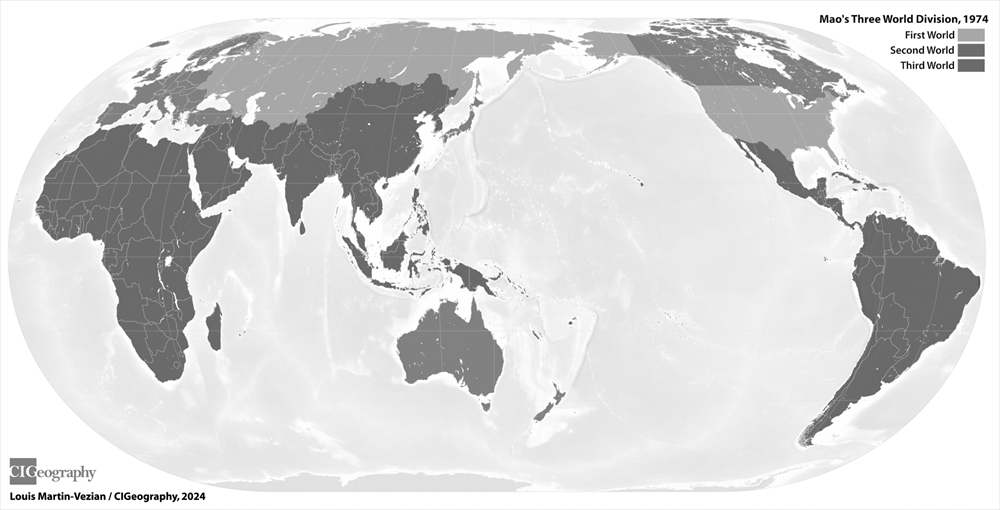

At the time of his wooing the two U.S. national security advisers, Mao had been including the United States in the same despised hegemonic camp as the Soviet Union for over a decade. In early 1974, he explained to Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda that the two superpowers could be overcome if China and the rest of the developing world created an international united front. In fact, the world was divided into three camps: the United States and the Soviet Union (hegemony seekers and “biggest international exploiters”) were in the first; Japan, Europe, Australia, and Canada (in various stages between the camps of oppressors of developing countries and countries oppressed by the superpowers’ bullying) were in the second; and Africa, Latin America, and Asia, including China and other oppressed nations at the forefront of the struggle against the superpowers, were in the third. Mao’s so-called Theory of the Three Worlds (see Figure 3) was officially introduced to the world by Deng Xiaoping during his speech at the United Nations in 1974.59

FIGURE 3 Mao’s three worlds

Over a span of 35 years, Mao’s main objective was to resist powers whose expansion posed an existential threat to China’s strategic space. From facing Japan’s imperialism in the late 1930s and 1940s to facing the U.S. containment strategy since the 1950s and, in the aftermath of the 1960s Sino-Soviet split, facing Moscow’s “social-imperialism,” Mao’s geopolitical thinking was guided by the compelling need to free China from external aggression and encirclement. Although the “lines” and continental “vast areas” that he envisioned as ramparts against imperialism never came to pass, they are still worth pondering, both as embodiments of China-grown geopolitical thinking and as potential prototypes for future Chinese geostrategic configurations (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 4 Mao in 1967  SOURCE: World History Archive, Alamy Stock Photo.

SOURCE: World History Archive, Alamy Stock Photo.

Lessons Learned

As they embarked on their mission to study geopolitics, Chinese analysts emphasized the need for their work not to be confined exclusively to academic musings but to generate support for national policymaking. Geopolitics gives a sense of predictability, which can be comforting in times of perceived great geopolitical shifts and appreciable from a strategic planner’s perspective. Although not all Chinese scholars make explicit inventories of lessons that would be applicable to China, some main themes emerge from their writings as they apply geopolitical lenses to survey their country’s international security environment.

“Only a handful of countries can truly become the center of the world.”60 Together with Europe and the United States, China is one of the three major world political and economic plates that have their own “geophysical advantages, strategic depth, and vast ‘living spaces.’”61 Its geographic location, at the east of Eurasia and to the west of the Pacific Ocean, lets China occupy a “dominant position on the Asian geographical plate” and stand as the “natural center” of Asia.62 Its exceptional topography, vast territory, ample room for maneuver, abundant resources, large population, “people able to endure hardship and work hard, and countless heroes,” as well as its “national spirit that dares to prevail,” make China not only Asia’s center of gravity but the target of other powers’ envy.63 China is like “a piece of fatty meat,” Mao said once, “everyone wants to take a bite at it.”64

Eurasia is the main springboard to world hegemony. Eurasia has been and will remain the focal region of great-power competition. Influenced by geopolitical theories, the United States never abandoned its grand strategy aiming at controlling Eurasia. Whether it translated in the past into Soviet containment or more recently into the Indo-Pacific strategy, the American hegemon has been pursuing the same set of objectives: preserving its global dominance and preventing the emergence of a competing power on the Eurasian continent, including through the use of its military alliance system.65 As the 2013 Science of Military Strategy notes:

-

- For more than sixty years after the war, the United States consistently treated Western Europe and East Asia as its strategic bridgeheads, and treated the arc- shaped zone along the periphery of the Eurasian continent, from Northeast Asia to Southeast Asia to South Asia to the Middle East to the Balkans, as a geopolitical battleground.66

The U.S. containment of China is inevitable because its rise threatens U.S. hegemony, most of all on the Eurasian continent.67 It would be “laughably naïve” to think this trend started in 2008 just “because someone declared that ‘China is getting stronger.’”68 Instead, the U.S. Department of Defense had already identified in the late 1980s the rise of China as the biggest future challenge to the United States, surpassing the threat posed by the Soviet Union.69 The 2001 Quadrennial Defense Review made it clear that the United States would actively squeeze China’s strategic space, which it had started to do after the Cold War by expanding its “geostrategic encirclement of China’s maritime environment” and by strengthening its “North and South anchors” (its alliance with Japan, South Korea, and Australia).70

Having established the importance of thinking “in space” as a basis for the formulation of national grand strategies and the reordering of the world, the next step was “drawing China’s geostrategic map” 71 that would accompany the definition of the country’s grand strategy and inform its future strategic direction. This required first determining China’s position on the geopolitical chessboard. Does it belong to the continental or maritime powers category? What are the constraints on its strategic space? How can it break through these constraints? The next chapters will examine each of these questions in sequence and describe how China found its place in the world, both figuratively and literally.

Nadège Rolland is Distinguished Fellow for China Studies at the National Bureau of Asian Research. Her NBR publications include China’s Eurasian Century? Political and Strategic Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative (2017), “China’s Vision for a New World Order” (2020), and “A New Great Game? Situating Africa in China’s Strategic Thinking” (2021).

Read the chapters online:

Introduction: Mapping China’s Strategic Space

Chapter 2: The Return of Geopolitics

Chapter 3: “Positioning” China: Power and Identity

Chapter 4: The Logic and Grammar of Expansion

Chapter 5: Conclusion: A New Map?

IMAGE CREDITS

Banner illustration by Nate Christenson ©The National Bureau of Asian Research.

ENDNOTES

- Pierre Buhler, “Puissance et géographie au XXIème siècle” [Power and Geography in the 21st Century], Géoéconomie, no. 1 (2013): 147.

- Sven Holdar, “The Ideal State and the Power of Geography: The Life-Work of Rudolf Kjellén,” Political Geography 11, no. 3 (1992): 319. Together with German geographer and ethnographer Fredrich Ratzel, of “Lebensraum” fame, Kjellén founded the German geopolitical school at the turn of the twentieth century.

- Halford J. Mackinder, “The Geographical Pivot of History,” Geographical Journal 23, no. 4 (1904): 422.

- Shi Yinhong, “Shijie xiandaishi shang de diyuanzhengzhi hongguan jili ji qi daguo guoyun xiaoying” [Geopolitical Macro Mechanisms in Global Modern History and Their Effects on Great Powers’ National Fortunes], Aisixiang, January 5, 2019, https://www.aisixiang.com/ data/114392.html.

- Shellen Xiao Wu, Birth of the Geopolitical Age: Global Frontiers and the Making of Modern China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2023), 3.

- Wu, Birth of the Geopolitical Age, 134–43. Geography was another scientific discipline imported from the West during that period. See Rachel Wallner, “Science, Space, and the Nation: The Formation of Modern Chinese Geography in Twentieth-Century China” (master’s thesis, Department of Asian Studies, University of Oregon, 2014).

- Liu Xiaofeng, “Guo zhi youhuan yu diyuanzhengzhi yishi” [National Anxieties and Geopolitical Consciousness], Hainan daxue xuebao 1 (2021).

- Ibid.

- Wu, Birth of the Geopolitical Age, 140.

- Ge Hanwen, “Diyuanzhengzhi yanjiu de dangdai fuxing ji qi Zhongguo yiyi” [The Contemporary Revival of Geopolitical Studies and Its Significance for China], Guoji zhanwang, no. 2 (2015): 81.

- Qin Qi et al., “1992 yilai guoneiwai diyuanzhengzhi bijiao yanjiu: Jiyu dilixue shijiao de fenxi” [A Comparative Study on Foreign and Chinese Geopolitical Studies since 1992: An Analysis from the Perspective of Geography], Dilikexue fazhan 36, no. 12 (2017).

- Lu Dadao and Du Debin, “Guanyu jiaqiang diyuanzhengzhi diyuanjingji yanjiu de sikao” [Some Thoughts about Strengthening Geopolitics and Geoeconomics Research], Acta Geographica Sinica 68, no. 6 (2013).

- Ibid.

- Pan Zhongqi, “Diyuanxue de fazhan yu Zhongguo de diyuanzhanlüe: Yi zhong fenxi kuangjia” [The Development of Geopolitics and China’s Geostrategy: An Analytical Framework], Guoji zhengzhi yanjiu, no. 2 (2008).

- Hu Angang et al., “Daguo xingshuai yu Zhongguo jiyu: Guojia zonghe guoji pinggu” [The Rise and Fall of Great Powers and Opportunities for China: An Assessment of Comprehensive National Power], Economic Herald, no. 3 (2017).

- Ibid.

- Du Debin and Ma Yahua, “Zhongguo jueqi de guoji diyuanzhanlüe yanjiu” [Research on the International Geostrategy of China’s Rise], World Regional Studies 21, no. 1 (2012).

- Du Debin et al., “1990 nian yilai Zhongguo dilixue zhi diyuanzhengzhixue yanjiu jinzhan” [Progress in Geopolitics of Chinese Geographical Research since 1990], Dili yanjiu 34, no. 2 (2015).

- Jiang Shigong, “Diyuanzhengzhizhanlüe yu shijie diguo de xingshuai: Cong ‘zhuangnian Maijinde’ dao ‘laonian Maijinde’” [Geopolitical Strategy and the Rise and Fall of World Empires: From “Mature Mackinder” to “Old Mackinder”], Zhongguo zhengzhixue 2 (2018).

- Liu Xiaofeng, “Meiguo ‘ezhi Zhongguo’ lun de diyuanzhengzhixue tanyuan” [Exploring the Geopolitical Origins of the U.S. “China Containment” Theory], Guowai lilun Dongtai 10 (2019).

- Fang Xu, “Yi dakongjian zhixu gaobie pu shi diguo” [Saying Farewell to Universal Empire with a Greater Space Order], Kaifang shidai 4 (2018).

- See the prolific writings of Zhang Wenmu, including his book On Chinese Sea Power (Lun Zhonggo haiquan) published in 2009 and his three-volume China’s National Security Strategy from a Global Perspective (Quanqiu shiye zhong de Zhongguo guojia anquan zhanlüe) published in 2010.

- Wang Fenglong and Liu Yungang, “Lun Zhongguo gudai diyuanzhanlüe zhiding zhong de ‘quanheng’: Yi ‘Yan Tie lun’ wei li” [On “Weighing Cost-Benefit” in Ancient China’s Geostrategic Making: The “Discourses on Salt and Iron” as a Case Study], Dili kexue 39, no. 9 (2019). The “Discourses on Salt and Iron” is the record of a debate held in 81 BCE (Han dynasty) over the establishment of state monopolies meant to bring new sources of income in order to, among other reasons, cover the cost of imperial expansion.

- Du Debin and his colleagues were consulted as subject matter experts on China’s responses to issues related to maritime disputes and Japan’s energy security dilemma. Their “expert consultation opinions” were sent to the Chinese Communist Party Central Committee Office and the State Council’s General Office. See Du et al., “1990 nian yilai Zhongguo dilixue zhi diyuanzhengzhixue yanjiu jinzhan.”

- Qin Gang, “Implementing the Global Security Initiative to Solve the Security Challenges Facing Humanity” (speech, February 21, 2023), https://www.mfa.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202302/t20230222_11029589.html. See also Xi Jinping’s speech at the 20th National Party Congress in October 2022, https://english.www.gov.cn/news/topnews/202210/16/content_WS634b85a4c6d0a757729e1480.html; the PRC’s 2019 defense white paper, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-07/24/c_138253236.htm; Hu Jintao’ s remarks in January 2011, https:// www.chinadaily.com.cn/video/2011-01/21/content_11895011.htm; Wen Jiabao’s remarks in June 2004, http://www.china.org.cn/english/ international/99594.htm; Jiang Zemin’s speech at Harvard University in November 1997, https://china.usc.edu/president-jiangs-speech- harvard-university-1997; and Deng Xiaoping’s speech to the UN General Assembly in April 1974, https://www.marxists.org/reference/ archive/deng-xiaoping/1974/04/10.htm.

- This function is acknowledged by a non-trivial number of scholars. See for example, Lu and Du, “Guanyu jiaqiang diyuanzhengzhi diyuanjingji yanjiu de sikao”; Ge, “Diyuanzhengzhi yanjiu de dangdai fuxing ji qi Zhongguo yiyi”; Ning An, Xiaomei Cai, and Hong Zhu, “Gaps in Chinese Geopolitical Research,” Political Geography 59 (2017): 136–38; Hu Zhiding et al., “Weilai shinian Zhongguo diyuanzhengzhixue zhongdian yanjiu fangwen” [Key Research Directions in Chinese Geopolitics for the Next Decade], Dili yanjiu 36, no. 2 (2017); Li Hongmei, “Diyuanzhengzhi lilun yanbian de xin tedian ji dui Zhongguo diyuanzhanlüe de sikao” [New Characteristics of the Evolution of Geopolitical Theory and Some Thoughts on China’s Geostrategy], Guoji zhanwang 6 (2017); and Qin et al., “1992 yilai guoneiwai diyuanzhengzhi bijiao yanjiu: jiyu dilixue shijiao de fenxi.”

- Liu Miaolong, Kong Aili, and Tu Jianhua, “Diyuanzhengzhixue lilun, fangfa yu jiushi niandai de diyuanzhengzhixue” [Theory and Methods of Geopolitics and the Study of Geopolitics in the 1990s], Human Geography 10, no. 2 (1995).

- Pan, “Diyuanxue de fazhan yu Zhongguo de diyuanzhanlüe: Yi zhong fenxi kuangjia,” 27.

- Wang Jisi, “Guanyu gouzhu Zhongguo guoji zhanlüe de jidian kanfa” [Some Views on Building China’s International Strategy], Studies of International Politics 4 (2007).

- Hu et al., “Weilai shinian Zhongguo diyuanzhengzhixue zhongdian yanjiu fangwen.”

- See the 2012 National Social Sciences Foundation project “Research on Post–Cold War Development, Characteristics, and International Political Significance of Geopolitical Thought on World Countries” (reference 12CGJ022).

- Ge, “Diyuanzhengzhi yanjiu de dangdai fuxing ji qi Zhongguo yiyi.”

- Liu, “Guo zhi youhuan yu diyuanzhengzhi yishi.”

- Hu Wei, Hu Zhiding, and Ge Yuejing, “Zhongguo diyuan huanjing yanjiu jinzhan yu sikao” [Progress and Reflection on China’s Geo- environment Research], Progress in Geography 28, no. 4 (2019): 481.

- Song Tao, Lu Dadao, and Liang Yi, “Daguo jueqi de diyuanzhengzhi zhanlüe yanhua: Yi Meiguo wei li” [The Evolution of Great Powers’ Geostrategy during Their Rise: The United States as a Case Study], Geographical Research 36, no. 2 (2017): 216–18.

- Zhang Wenmu, “Zhongguo diyuanzhengzhi de tedian ji qi biandong guilü” [Characteristics and Changing Laws of Chinese Geopolitics], Taipingyang xuebao 21, no. 1 (2013).

- See, for example, Song, Lu, and Liang, “Daguo jueqi de diyuanzhengzhi zhanlüe yanhua,” 221–22; and Dai Peng, “Zhongguo zhoubian diyuanzhanlüe yanjiu” [Study of China’s Peripheral Geostrategy] (graduate thesis, PLA Information Engineering University, 2006).

- Shi, “Shijie xiandaishi shang de diyuanzhengzhi hongguan jili ji qi daguo guoyun xiaoying.”

- Fang, “Yi dakongjian zhixu gaobie pu shi diguo.”

- Wei Wenying, Dai Juncheng, and Liu Yuli, “Diyuan wenhua zhanlüe yu guojia anquan zhanlüe gouxiang” [Geocultural Strategy and the Conceptualization of National Security Strategies], World Regional Studies 25, no. 6 (2016).

- Song Tao et al., “Jin 20 nian guoji diyuanzhengzhixue de yanjiu jinzhan” [Twenty Years of Progress in the Study of International Geopolitics], Acta Geographica Sinica 71, no. 4 (2016).

- Lu Junyuan, “Meiguo dui Hua diyuanzhanlüe yu Zhongguo heping fazhan” [America’s Geostrategy toward China and China’s Peaceful Development], Human Geography 21, no. 1 (2006).

- Du and Ma, “Zhongguo jueqi de guoji diyuanzhanlüe yanjiu”; and Song et al., “Jin 20 nian guoji diyuanzhengzhixue de yanjiu jinzhan.”

- Fang Xiaozhi, “Burejinsiji diyuanzhengzhi sixiang de zai quanshi” [A Reinterpretation of Brzezinski’s Geopolitical Thought], in Zhongguo zhoubian diyuan huanjing xin qushi: Lilun fenxi yu zhanlüe yingdui [New Trends in China’s Peripheral Geo-environment: Theoretical Analysis and Strategic Responses], ed. Liu Ming (Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press, 2016), 49–64.

- Hu Zhiding and Wang Xuewen “Da guo diyuanzhanlüe jiaohuiqu de shikong yanbian: Tezheng, guilü qi yuanyin” [Spatio-Temporal Evolution of Great Powers’ Geostrategic Confluence Zones: Characteristics, Patterns, and Causes], Tropical Geography 39, no. 6 (2019).

- Wei, Dai, and Liu, “Diyuan wenhua zhanlüe yu guojia anquan zhanlüe gouxiang.”

- Su Hao, “Diyuan zhongxin yu shijie zhengzhi de zhidian” [Center of Gravity and the Pivot of World Politics], Contemporary International Relations 4 (2004).

- Wei, Dai, and Liu, “Diyuan wenhua zhanlüe yu guojia anquan zhanlüe gouxiang.”

- Ge, “Diyuanzhengzhi yanjiu de dangdai fuxing ji qi Zhongguo yiyi”; and Liu, “Guo zhi youhuan yu diyuanzhengzhi yishi.”

- Liu Yungang and Wang Fenglong, “Zhongguo gudai zhengzhi dili sixiang tanjiu” [An Exploration of Ancient Chinese Political Geography Thought], Progress in Geography 36, no. 12 (2017).

- The phrase “vertical alliances, horizontal coalitions” refers to two contending strategies during the Warring States Period (from 5th century BCE to the unification of China under emperor Qin Shihuangdi in 221 BCE). Six kingdoms (Qi, Chu, Yan, Han, Zhao, and Wei) were trying to cope with Qin’s growing power and expansionism. Supporters of the “vertical alliance” along a north-south axis advocated an alliance among the six weaker states to balance against Qin, while supporters of the “horizontal coalition” advocated aligning with Qin along an east-west axis. Qin divided the contenders and conquered them one by one.

- Zheng Yongnian, “Bianjiang, diyuanzhengzhi he Zhongguo de guoji guanxi yanjiu” [Borderlands, Geopolitics and China’s International Relations], Aisixiang, July 29, 2012, https://www.aisixiang.com/data/55889.html. See also Jiang Bin, “Zhongguo Gongchandang diyuanzhanlüe sixiang de lishixing sikao” [Historical Reflections on the Geostrategic Thinking of the Communist Party of China], Journal of PLA Nanjing Institute of Politics 2 (2012).

- Liu, “Guo zhi youhuan yu diyuanzhengzhi yishi.”

- Mao first mentioned the existence of such a “vast zone” during an interview with American reporter Anna Louise Strong: “The United States and the Soviet Union are separated by a vast zone which includes many capitalist, colonial and semi-colonial countries in Europe, Asia and Africa. Before the U.S. reactionaries have subjugated these countries, an attack on the Soviet Union is out of the question.… True, these military bases are directed against the Soviet Union. At present, however, it is not the Soviet Union but the countries in which these military bases are located that are the first to suffer U.S. aggression. I believe it won’t be long before these countries come to realize who is really oppressing them, the Soviet Union or the United States. The day will come when the U.S. reactionaries find themselves opposed by the people of the whole world.” The full interview transcript is available at https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/strong-anna-louise/1946/talkwithmao.htm.

- Liu, “Guo zhi youhuan yu diyuanzhengzhi yishi.”

- Mao Zedong,On Protracted War(1938), available at https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-2/mswv2_09.htm.

- “Memorandum of Conversation between Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and Henry Kissinger,” February 17, 1973, available at https:// digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/memorandum-conversation-between-mao-zedong-zhou-enlai-and-henry-kissinger. See also Gong Li, “‘Yi tiao xian’ gouxiang he huafen ‘sange shijie’ zhanlüe” [The “One Line” Concept and Division of the “Three Worlds” Strategy], National Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences, March 1, 2012, http://www.nopss.gov.cn/GB/219470/17264676.html.

- Wang Jisi, “Dongxinanbei, Zhongguo ju ‘zhong’: Yi zhong zhanlüe daqiju sikao” [East, West, South, North and China in the Middle: Pondering Over the Strategic Chessboard], China International Strategy Review (2013). In February 2015, Wang published an edited version of his article in English in the American Interest, entitled “China in the Middle,” https://www.the-american-interest.com/2015/02/02/china-in-the-middle.

- Deng Xiaoping (speech at the UN General Assembly, New York, April 10, 1974), available at https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/ deng-xiaoping/1974/04/10.htm

- Wang, “Dongxinanbei, Zhongguo ju ‘zhong.’”

- Ibid.

- Zhang Wenmu, “Zhongguo diyuanzhengzhi de tedian ji qi biandong guilü.”

- Jiang Yong, “Dili buru renhe, diyuan buji renyuan: Mao Zedong guojia anquan sixiang yanjiu” [A Favorable Location Is Not as Good as People at Peace, a Geoposition Is Not as Good as an Affinity with the People: A Study of Mao Zedong’s National Security Thought], Utopia, November 29, 2021, http://www.wyzxwk.com/Article/guofang/2021/11/445598.html.

- Ibid.

- Hu and Wang, “Da guo diyuanzhanlüe jiaohuiqu de shikong yanbian.”

- Zhou Xiaosong, ed.,

- Du and Ma, “Zhongguo jueqi de guoji diyuanzhanlüe yanjiu”; and Wang Enyong and Li Guicai, “Cong diyuanzhengzhixue kan Zhongguo de zhanlüe taishi” [China’s Strategic Situation from the Perspective of Geopolitics], Renwen dili, no. 1 (1990); and Dai, “Zhongguo zhoubian diyuanzhanlüe yanjiu.”

- Liu, “Guo zhi youhuan yu diyuanzhengzhi yishi.”

- Liu Xiaofeng attributes this conclusion to a “strategic warning put forward by Andrew Marshall.”

- Lu, “Meiguo dui Hua diyuanzhanlüe yu Zhongguo heping fazhan.”

- Song, Lu, and Liang, “Daguo jueqi de diyuanzhengzhi zhanlüe yanhua.”

Science of Military Strategy

- (Beijing: Military Science Press, 2013), trans. China Aerospace Studies Institute.